By Lia Chang

AsAmNews Arts & Entertainment Reporter

For four decades, Chinese American actor Tzi Ma has worked in film, television, and on stage creating a distinguished body of work.

Ma can currently be seen in the first six episodes of Season 5A of Hell on Wheels on AMC on Demand. Hell on Wheels is my father’s favorite show and is a contemporary Western which tells the story of Cullen Bohannon (Anson Mount), whose experience with Union Pacific’s construction of the first transcontinental railroad takes him westward into a lawless melting pot of a town called Hell on Wheels.This season, Hell on Wheels focused on how immigrant Chinese workers became an integral part of the construction of the railroad.

Ma plays Tao, who is originally from a village in Guangdong in Southern China, and is now “head man” for a group of Chinese railroad workers on the Central Pacific Railroad. A former scholar, his natural leadership abilities and facility with the English language make him essential to Cullen’s work on the Central Pacific. He’s a highly capable man, but harbors a secret, and goes out of his way to avoid attention.

Ma just wrapped Denis Villeneuve’s sci-fi movie Story of Your Life in Montreal, where he portrays the pivotal role of General Shang opposite Amy Adams, Jeremy Renner and Forrest Whitaker. Other films in the can include Pali Road, with Elizabeth Sung as his wife, and the period psychological drama Diablo with Scott Eastwood. You can also catch him on October 16th, when USA’s Satisfaction returns for its second season where Ma plays the Zen Master.

Below are excerpts from my interview with Ma, where he discusses Hell on Wheels, what role the Chinese played in the building of the railroads, his early theater days with Tony award-winning playwright David Henry Hwang, how he transitioned into TV and film, and how he’d like Asian American actors to discover their own brand of sexy.

Lia: What did it feel like to come home to your community and such a receptive audience at the Asian American International Film Festival?

Tzi: Warm and fuzzy. That’s the first thing that came to mind. Very proud that all these friends and family came to support the evening. I brought something back that everybody can be proud of. It’s not just a piece, it’s not just about artistic expression. This is a well funded, highly polished well put together TV show. The subject matter is so close to the community’s heart and also it is a sheer historical moment. This has never been done before. No on has ever seen anything like this in the way it is being presented in telling the story with really wonderful writing, great characters. I was so happy that the community really got a chance to see something that they really should be very proud of.

I am also happy that our executive producer and show runner John Wirth was there, a very accomplished producer who stood in front of an audience that is so knowledgeable. The people know the story and you can’t get anyway with anything.

Lia: What does it mean to you have this story told?

Tzi: You should see some of the reactions on Twitter. People were talking, “Oh my God, these people are actually speaking Cantonese properly. Hurray!”

You have this kind of response to people who are going to continue to do shows. That’s important. It’s important that the community is showing up to let you know that you need to tell these stories the way it should be told in it’s proper historical perspective, or we are going to bust you. It was really exciting. John was so appreciative. He said,”Not only are they warm and supportive, but the fact that they know what’s real, what’s important, and that they’ve come out to support.”

I couldn’t find a better way to share this, really, with all the people I’ve know most of my adult life, my formative years. It’s tremendous to have this kind of environment for us. Hopefully, there’s a lot more to come. Hopefully, because of these experiences, there will be more stories produced with meaning to us, to Asian Americans. The fact that the community also learned a lesson: that they need to come out and be accounted for. It should be something that they are more vocal about. They need to let people know that they support this. Advertisers need to know. They need to pay attention because this is a very important segment of the population that spends a lot of money. I think it is a lesson bridging all of these cultural gaps that we have. We’re taught one way, but we are also taught another way. We need to participate as Americans. Hopefully all of that will start to pan out and be much more effective in terms of how they tell our stories. And not just gloss over, not just background color. It is important for us to be the focal point of series and films.

Lia: How did Hell on Wheels come to you?

Tzi: They called around March and asked for my availability and interest in the show. I knew about the show. I knew the show in its first season. People in the community, back in season one when the pilot was shot and the fact that it was going to happen, people were asking, “Are you going to tell our story?” I tell you, they couldn’t answer that question because they didn’t know if the show was going to go one season, two seasons. I think the powers that be, knew they were going to tell the story chronologically. You couldn’t promise to tell the Chinese story because that didn’t happen until the end. In some ways, it’s kind of weird or strategic for AMC, that they didn’t really address it early on. We did ask, “What about telling the Chinese side of it?” There was no answer from them. Now we understand, the fact that they had the chance to do the whole building of the railroad story, it is a fitting end for the series. Season 5A is devoted to the most difficult part of the connection of East and West on the railroad.

The problem was that I was pretty busy. I had a lot on my plate. I was going to shoot a film in Europe, either in Lithuania or some other locale. I was also shooting a series in Atlanta, Satisfaction. We were going into our second season, and it didn’t look like I was going to be available to do it. So finally, my manager, Andrew Ooi, really worked hard to give me a hard out for the film, that I was going to finish by April 20th, no matter what. Actually that film didn’t happen because the financing fell through. But I still had Satisfaction to deal with. Satisfaction was always very cooperative.

The first season I was shooting 24: Live Another Day in London, and they were able to accommodate my schedule overseas and were able to shoot three episodes, back to back in one sitting. So this year, they did the same thing. I am grateful to them for allowing me to do Hell on Wheels.

So they sent me a NDA. I had to sign that before they sent us any scripts. They sent me the first two scripts and I thought, “These guys really did their homework.”

I basically knew the story; I’m very familiar with the story because of David Henry Hwang’s The Dance and The Railroad, a play about these two Chinese railroad workers building the continental railroad that I did in the 80’s. It was a two character play, with me and John Lone at The Public Theater. So we know something about that time period and what these people are about. The first two scripts totally rang true. They found Professor Gordon H. Chang from Stanford, who has devoted his life to trying to research this story of us building the railroad. In that sense, I was really happy with it. I couldn’t be happier with the writing. Because they are so well researched, they feel confident and unencumbered to tell the story dramatically. They were able to tell a story in a compelling way, through characters. They really understand the subject. They didn’t write characters that are just black and white. All of these characters have their flaws. Everybody has their reasons of being. They exist in a time, that’s what resonates with the people in the audience.

Lia: What does it mean to you to have a show like Hell on Wheels tell the story of the Chinese and the railroads? Did John Wirth and the writers encourage your input with regard to the role and the story being told? What else did you bring to the character?

Tzi: I felt Tao shouldn’t be this British engineering school guy. I felt that he should be more of a working-class guy, who did have an opportunity to go to a missionary school. I really wanted it to be an American school. That’s how open these guys were. With the British character, they are always presenting this upper crust, which I did not want to represent. The missionaries provided these unique education opportunities because they wanted you to find Jesus. It’s all good for them, they don’t care what class you come from as long as they can convert you. Obviously they weren’t that successful, even in history, some were converted, the Baptists are very strong in China. I wanted this guy, the fact that he was bilingual, he was American influenced, he’s really into this new way of governing called democracy, a republic, that people get to be elected. It’s fascinating to him.

This was discussed with John and all of the writers. And since Byron covered the British end, they loved it because it offered a kind of contrast. It widens the net for us to see these different kinds of colors, from all these different characters. If not, then everything is kind of lumped into this period British thing. I am trying to break that kind of mold. Every time they get into this period thing, they have to talk like they’re from Britain. I said, “No, I think we have to think that period dialogue does not have to be sound like everybody is from England. We have a history too.” I really wanted that.

You have to reconcile with certain things. There were certain things that could not be done. You couldn’t put everybody in queues. So, that is difficult. It’s a compromise we had to make. Normally, everybody would have a queue.

So in order for Fong to work and to make her, more him, short hair is definitely something you need to do. So I need to justify that too, because she is in disguise. Normally she would have long hair and she would braid it, but she would look too feminine. We have to make that kind of connection. I felt it was important for Tao to really know that Fong would probably be here, staying in America, and that he would go home to the reform in China. It enriches the character. He was going to go back. He was going to be the Sun Yat Sen if he had lived. But he didn’t. Unfortunately, he gets killed in the show. And that of course is important as well because it adds that kind of dramatic bridge that the audience is going to react too. And they did. Twitter just lit up when that episode aired. People were, “Oh my God, no, they killed Tao!” That’s pretty weird. I’ve never experienced anything like it because I’ve never done social media in any way. My niece actually set it up for me. My phone was jumping off the table it was vibrating so much. The reaction to his death was overwhelming. I’ve never seen anything like it. It was crazy. It was an eye opener for me.

In 2015, there are only seven episodes. You can see the transition after my death; the transition is going to focus on the race itself, how both sides got to the middle in Utah. You can see the switch already. So it was important that we promote and got the community out there to support.

Lia: What was it like to work with Angela and Byron?

Tzi: It was kind of cool. It was three generations. You have Byron, who is in the middle. I’m like the old guard. Time passes and you don’t really see it until you are looking at Byron and Angela, who just graduated from Duke a year ago. It’s been a great opportunity for her and showcases her talent. She’s really gifted. It is enlightening. Learning never stops. I look at Byron and I look at Angela and I watch the way they approach their work. It is something that I can’t help. It is within my DNA to continuously observe. That is what I do. That is what any actor would do, to observe and see how people work, what they bring to the table, how serious they are. It’s very important to me. Particularly when you are an actor of the same shade of color as me. I keep an eye on it. I need to know what the pool is like. I need to know what’s coming down in the pipeline. I need to know who I am going to be working with in the future. And knowing what our future looks like, will they be representing the community well? I am very encouraged that you have these guys who are very serious about their work, who devote a lot of time in what they pursue. It’s been a wonderful experience and I’ve learned a lot from them.

Lia: How old were you when you decided to pursue a life in the arts?

Tzi: I was 23. It was something I always wanted to do. I was going to do that no matter what, come hell or high water. The reactions in a Chinese American family, the fact that you are going into this business, it comes from a good place, a practical place. They don’t want to see you struggle. It builds character. The fact that they were not happy that I took this road, I use it when the perfect opportunity arises. It’s a blessing. I didn’t have to guess what my life path would be. I knew what my life path was going to be. It’s just how was I going to get there? That was the question.

Lia: Can you describe your early years in New York when you started your acting career in theater?

Tzi: It was so exciting. In the 70’s, there was money around because there was a tremendous amount of funding. There were at least two or three federal agencies that gave a lot of money to the arts. We don’t have that anymore, it’s gone. They don’t exist, which is a shame. Doing theater in New York was really exciting. I never thought about myself as an actor of color. At the time, it was about exploration, it was about doing experimental theater. There was so much funding. We were in residence at Nassau Community College because they had money. It’s a community college so you had the chance to teach, which is kind of weird because you didn’t really know anything. The good thing was that I was only teaching movement. That was something I was most familiar with. I was earning money while I was studying as an actor. You can’t find those environments today where you can earn a living and do what you love to do, develop your skills and craft as an actor.

The first play I ever did was for an audience of 5,000 to 10,000 people. It was an outdoor theater at Roosevelt State Park. One of those Shakespeare in the Park kind of experiences. The show was Monkey King in the Yellow Stone King. It was an adaptation of a Beijing Opera. It was 1975 and we’re doing amazing experimental stuff, to introduce a Long Island audience to Beijing Opera. Are you kidding me? It was an out-of-body experience. Full Beijing opera makeup. I was playing Monkey King. I’ve been very blessed in that sense. Very early on in my career, I was able to play leading roles. I’ve never felt that I needed to be the second spear chucker from the left. I never had that experience. I’ve always had been able to participate in a manner that was meaningful to myself, and hopefully to the audience. It was really an auspicious beginning. I’ve always been grateful. I’ve worked with some wonderful actors and directors and collaborators of the theater.

Photo by Craig Schwartz

Lia: David Henry Hwang wrote The Dance and the Railroad for you, and you won a CINE Golden Eagle Award and Dramalogue Award for Best Director and Best Choreographer. Can you elaborate on working with David then, and then having the opportunity to revisit his work with Flower Drum Song and Yellow Face?

Tzi: When is this going to happen was always the question. It took that long. From 1980, I’ve worked with David so often and so much. He is one of my best friends. I’ve done at least five or six of his plays – FOB, Yellow Face, Flower Drum Song. I did his film, Golden Gate. And I had many more opportunities to work with David. In many ways I feel bad that I couldn’t be a better friend to him. I could have done Golden Child, all of those wonderful plays that were open to me to do. It’s all economics. Theater is really getting to a point where it is an elitist endeavor, where you really have to have money to do it. A lot of those opportunities, like I didn’t get to do Yellow Face in New York was because of money. I couldn’t afford to do another play. We already did it in LA. On the other hand, I was happy that someone else got to do those wonderful roles in Yellow Face. That’s the silver lining.

Working with David has always been a pleasure. It’s so collaborative. He’s so giving and generous with his time. I always tell him, he’s too generous. I think he needs to hold on to his writing a little more. The Dance and the Railroad, he rewrote every day. We’d go to rehearsal; we’d go to lunch at 1 p.m. By the time we came back, we’d have changes. That’s how he works. He is so gifted, so quick. He’s actually made for TV. A credit to David that he could make a living as a playwright is remarkable. Most playwrights are broke.

Lia: How did In Perpetuity Throughout the Universe, written by Emmy award nominee Eric Overmyer, change the course of your career?

Tzi: It’s all timing really. In 1988, there was the writers strike. That was the longest writers strike in history that they actually went out for four to six months. At that time, I was doing the play at Southcoast Rep in Orange County. Normally, these theaters, they are supposed to be showcases for actors so that people from film and TV can see whether or not they have any talent at all. If the season were going and TV and film production was in full swing, nobody would be going to Orange County to see a play. It was too far and too difficult to get to. The writers strike, they had nothing to do, they were bored out of their minds because they caught them flat-footed. The first strike they didn’t stock pile. They had nothing. They were doing reruns all the time.

At that time I wasn’t interested in TV or movies because I didn’t know the medium. The show was written for me and gave me an opportunity to do a lot of different things. I played three or four characters, very different, contrasting characters. Some subtle, some very dramatic. The main character that I played was this boyfriend of this white woman. They are ghostwriters. It was kind of quirky and edgy. It’s about the yellow peril, race. Unfortunately, some of the stuff that they covered in that play still rings true today about the right wing. All of these things were fascinating to the “Hollywood” crowd.

Doing theater, it’s all at night. I didn’t have much to do during the day. They started calling me to have meetings and to read. They had nothing to do. It was crazy. They would call and ask, “Does Tzi want to come up and have a meeting?” It was with these casting directors, I didn’t know who they were. It was kind of fun because I had nothing to do. The other thing that was fascinating was that I was a New York actor. Back in the day, if you were a New York actor, you were a better actor. There’s this bias. Obviously, we know that’s not true, but that was the reputation of the day. If you are a TV actor, you do TV. If you are a film actor, you do film. Very few crossovers and the fact that you are a New York actor, you must be Marlon Brando. You have that kind of edge. I am a New Yorker through and through, so I bring that into the room as well.

When the show closed in October on a Sunday, the strike was over on that same Sunday and the writers went back to work next day. Somebody’s doing something out in the ethers. It wasn’t me. I was working on Wednesday; L.A. Law was my first show. A nondescript role, it wasn’t specifically written Asian at all. He brought me in for a meeting and he gave me this monologue to read, with Steven Bochco in the room. Steven Bochco had nothing to do. It wasn’t because I was so great as an actor in cold reading. It was the piece. It was a fantastic monologue. Anybody that would have read that would have been great. Timing is something that you really can’t fathom and you can’t judge what it is going to do for you. It was a beautiful monologue about this lawyer who practiced law, but didn’t have a degree, didn’t pass the bar, never went to law school, and he’s defending himself. He sat there and told the entire story about his life on that one page – about where he is from, how much he loved justice versus the law. Even talking about it gives me chills. On Wednesday, I was working on L.A. Law.

Lia: What have been your favorite roles or projects and the most fulfilling?

Tzi: They are all fulfilling. It’s important for actors of color to pick and choose their projects and be more selective. I think it develops good taste. That you understand and that you know what you can do with the role and the script. Once I commit to a particular project, every project brings its uniqueness to it.

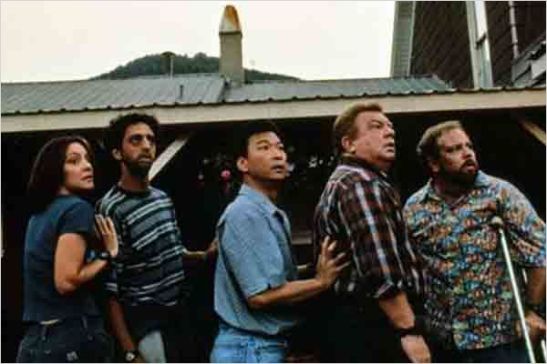

Dante’s Peak, big budget, $150 million, the role was an American role. No one ever questioned the ethnicity of these characters. They were all Americans. They were volcanologists; they worked for the United States Geological Survey. That’s what they do. It gave you the opportunity to be part of the American fabric. They were American scientists who go all over the world just to tell you this is going to blow. It’s a volcano that is going to blow. I appreciate that.

In Rapid Fire, I finally got to do an antagonist role. I used to turn those down all the time because I didn’t want to be the villain. Because that is all we would get, we would always portray these villains. But the difference in Rapid Fire, Brandon Lee was the hero. Brandon Lee gets the girl. When you have an Asian American hero on the screen, I can be the baddest motherfucker you’ve ever seen. And I’ll do it to the max. There’s value to that. After that, I’d get a lot of offers for these roles –being a bad guy with Steven Segal, being a bad guy with Jean-Claude Van Damme. I said no. Because they are not Asian Americans, they are not heroes. I want to see people of my skin, of my color as the hero, and a balance of good and evil of my race in this particular project. It had to be the same project. It couldn’t be separate projects.

The Ladykillers, working with the Cohen Brothers, this ensemble of crazy fun stuff that you do and you get to explore doing chain reaction with Morgan Freeman, Keanu Reeves. Million Dollar Arm with Jon Hamm. The Quiet American with Michael Caine. As an actor you are able to play these characters- Hinh was a true-life character. He was still alive when I did that role. We shot in Vietnam I got to meet that guy. A spy for 35 years and never caught. As an actor, I’ve met extraordinary people. You go and you meet President Obama and you shake his hand. But you get to be President Obama, not just shake his hand. That’s what it’s like. That’s the gift that we get as actors. We get a chance to play these real life characters who if they were Japanese, would be national treasures. Not just meeting them, but to be them. Every role has its place and meaning and I appreciate all of them.

Lia: Over the course of your career, what have been your observations of how Asian Americans and specifically Asian American men have been portrayed in film and television?

Tzi: There seems to be progress. I don’t separate film and television because it is our major export; it influences the entire world on how we are viewed. I think with The Mentalist, we’re still not sexy. That’s something that we need to work on. For the younger male actors, they need to think about their sexuality in their own way. Don’t do your normal sexy, your normal hunk. We have our own brand of sexy. We get too influenced by pop culture. I feel that their sexy is not our sexy. When we try to be their sexy, we’re not sexy.

Lia: What would you like to see change?

Tzi: I want us to go beyond what the majority culture is dictating to us. I want us to present us as us. I don’t want us to be so contained or marginalized. Online, we are taking center stage. We are the stars. We need to empower ourselves. The community needs to come out and support.

Ma’s impressive filmography includes such memorable characters as Cheng Zhi, nemesis to Kiefer Sutherland’s Jack Bauer on the hit series 24 and 24: Live Another Day, and playing opposite Tom Hanks in Joel and Ethan Coen’s remake of The Ladykillers.

Photo: FOX

Ma has had roles in the films Million Dollar Arm, Rush Hour, Rush Hour 3, The Quiet American, Akeelah and the Bee, Dante’s Peak, Chain Reaction, Golden Gate and Rapid Fire. His television credits include Satisfaction, Commander-in-Chief, Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D., Once Upon a Time, Hawaii Five-O, Grey’s Anatomy, Fringe, The Practice, Law & Order, ER, NYPD Blue, Boomtown and Chicago Hope.

The youngest of seven children born in Hong Kong, Ma was reared in New York City. His family ran the first Chinese American restaurant on Staten Island.

Lia Chang is an award-winning filmmaker, a Best Actress nominee, a photographer, and an award-winning multi-platform journalist. Lia has appeared in the films Wolf, New Jack City, A Kiss Before Dying, King of New York, Big Trouble in Little China, The Last Dragon, Taxman and Hide and Seek. She is profiled in FebOne1960.com Blog, Jade Magazine and Playbill.com.