Demonstrators march through New York City’s Manhattan Chinatown to fight for construction jobs for Chinese construction workers at Confucius Plaza on May 31, 1974. (Courtesy of Mary Uyematsu Kao)

By Melissa Young, AsAmNews Intern

Mary Uyematsu Kao experienced racism from an early age as a Japanese American growing up in the 1950s and ‘60s.

In kindergarten, she witnessed a cross burning on the front lawn of a Jewish family across the street from her family’s home. Young boys, inspired by World War II movies, would yell anti-Japanese slurs and throw rocks at her on her walk home from school. When her family tried to move to another neighborhood, residents there tried to petition them out. During the ‘60s, she watched the Black civil rights movement play out on TV.

These experiences galvanized Uyematsu Kao to become an activist in the Asian American movement during the ‘60s and ‘70s .

Drawing inspiration from the Black Power and anti-Vietnam War movements, the Asian American movement protested racism and U.S. militarism. It also advocated for solidarity between Asians and other people of color in the U.S. and globally.

As an undergraduate and then graduate student at UCLA, Uyematsu Kao photographed a myriad of events from the movement from 1969 to 1974. These included demonstrations in New York Chinatown protesting hiring discrimination, a Yellow Brotherhood fundraiser in Los Angeles, a pilgrimage to Manzanar, demonstrations against the Vietnam War and many more.

Her photos then went largely unpublished for decades, though she had always wanted to do a photography book. When she retired in 2018 after over 30 years at the UCLA Asian American Studies Center, she finally realized her dream.

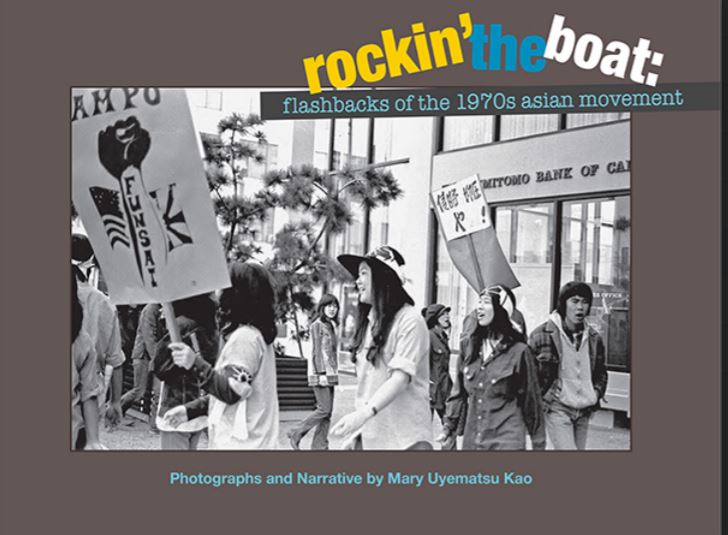

Her book Rockin’ the Boat: Flashbacks of the 1970s Asian Movement, published by the UCLA Asian American Studies Center in October 2020, features her more-than 400 photographs covering events of the Asian American movement from 1969 to 1974.

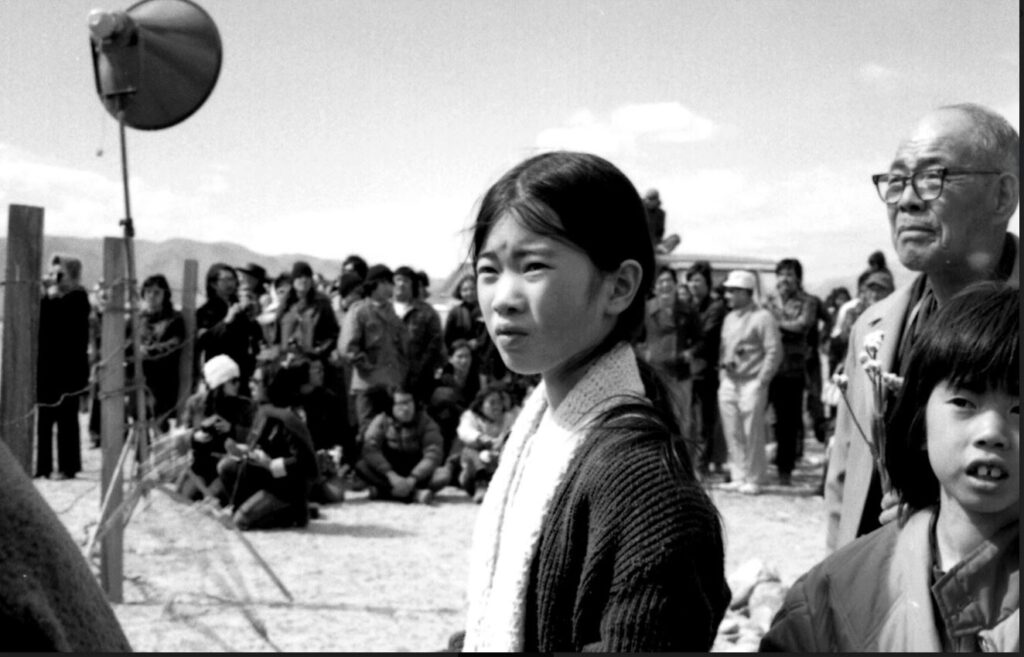

The book includes photos of the 1974 demonstrations in New York City’s Manhattan Chinatown over the Confucius Plaza high-rise construction project, a momentous moment she considers among the least documented in Asian American writings.

Uyematsu Kao said that Chinatown activists conducted an analysis and found that Chinatown’s immigrant residents were restricted to working in the garment and restaurant businesses.

During that time, there was a federally funded construction project to build a housing complex called Confucius Plaza in Chinatown. Asian Americans for Equal Employment advocated for Chinese construction workers to be hired for the project. Upon learning that the developer hired none of the 100 Asian construction workers who applied for the project, activists organized daily demonstrations to protest hiring discrimination.

Hundreds of protesters marched carrying signs in English and Chinese. Black and Puerto Rican construction workers, who had been organizing similar protests since more than a decade prior, joined the effort.

“The meticulously organized protest, similar to those that have been taking place at sites in Black and Puerto Rican areas for 11 years in the city, is something new to Chinatown. While residents have often complained of discrimination and short‐changing on city services, public protest has been rare,” the New York Times, reported on June 1, 1974.

Dozens of protesters were arrested during the demonstrations.

According to Uyematsu Kao, Asian construction workers learned from Black and Puerto Rican workers how to shut down a construction site in protest. They blocked construction at Confucius Plaza until the development company hired minority workers, including Asians.

“The most important thing in winning that was the unity of the Asian American workers with the Black and Puerto Rican construction workers,” she told AsAmNews. “It was important in terms of solidarity among people of color. And huge support from the Chinatown community came in the form of garment workers, senior citizens and high school kids coming out to demonstrations. That was really inspiring.”

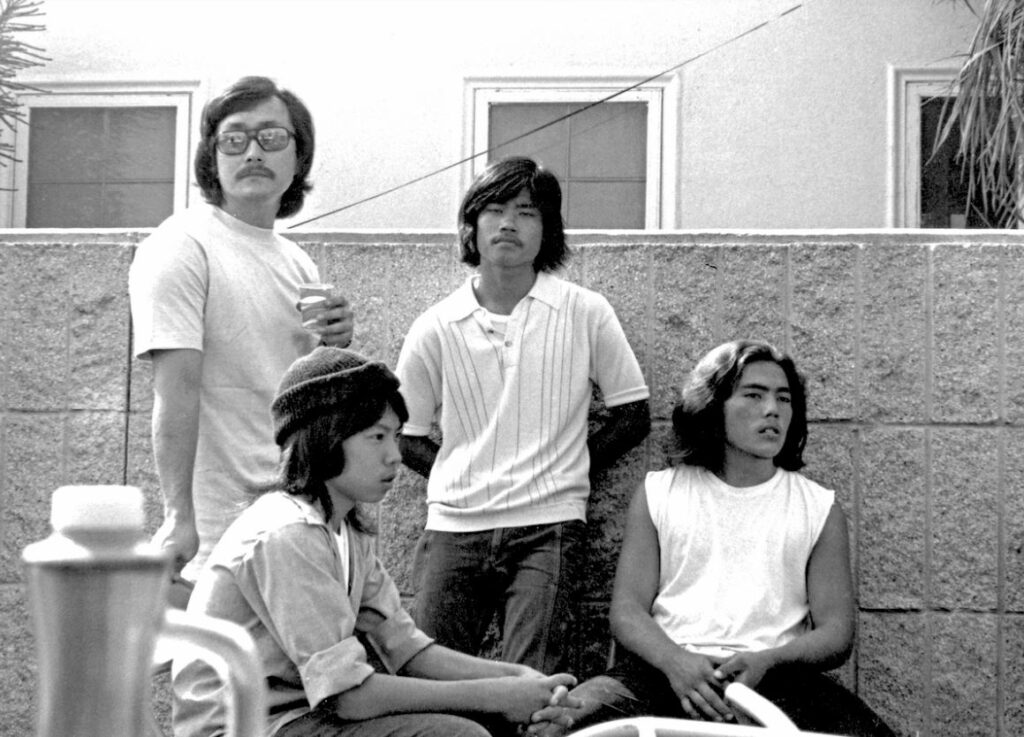

Uyematsu Kao also documented a pancake breakfast fundraiser for the Yellow Brotherhood, an LA-based self-help group modeled after the Black Panthers.

Founded by former Japanese American gang members, the Yellow Brotherhood worked to empower at-risk Asian American youth during a time when the LA Japanese community was facing a drug epidemic. According to Uyematsu Kao, the crowds at the pancake breakfast showed that the Yellow Brotherhood enjoyed significant community support.

The most important thing to know about the Asian American movement was that it was motivated by the Black liberation movement, Uyematsu Kao said. She views Malcolm X’s 1965 autobiography as galvanizing people of color to question and push back against racism.

“When he deconstructed that ‘White is right’ was wrong and basically tore it apart, that really gave all of us our identities back of who we were,” Uyematsu Kao said. “Instead of trying to assimilate and be White, which was the going norm at the time, it validated that people of color are perfectly legitimate and good people. That was a huge turnaround, and so that gave tremendous impetus to then us starting to ask our parents about the concentration camps of World War II for Japanese Americans.”

Uyematsu Kao believes that the 1970s Asian American movement raised consciousness among Asian American communities to continue working with other people of color groups, such as supporting Black Lives Matter and protesting U.S. detention camps detaining migrant children. She emphasizes the importance of continued solidarity between people of color.

“[The Black movement] opened the door for all people of color to start organizing and standing up for themselves, and now it’s a question of us all working together.”

Sandy Maeshiro, an activist from the Asian American movement who provided an interview for the book, told AsAmNews in an email, “Mary covers so many of the events that defined and changed our lives. The photographs document the day-to-day activities of the movement in all of its many facets — community events, campus and community demonstrations, and glimpses into the personal and political lives of the participants who made the Asian American movement so important. It’s a story that is told by those who actually participated in the events. The photos convey the passion, enthusiasm and belief in fighting for the social causes of the day: protest against the Viet Nam war, protests against Japanese imperialism, fighting the drug epidemic that plagued our communities, building community organizations and challenging the stereotypes of the ‘Quiet Americans.’”

Bea Dong of Eastwind Books in Berkeley, CA, said in an email comment, “Rockin’ The Boat is a treasure of black and white 35 mm film photographs taken by artist Uyematsu Kao on the 1970’s LA area Japanese American youth movement. With a photographer’s eye, Mary has captured the passion of youth, building a working class, community based, and multigenerational unity that inspired Asian American youth everywhere. From the Yellow Brotherhood, to the scores of courageous women who led the Southern California AA movement, the LA youth created a new political culture that spread from coast to coast. Through firsthand photography and narration, Rockin’ the Boat, reenacts this movement as only a visual retelling can accomplish.”

Harry Manaka, a reader of the book, told AsAmNews in an email, “Not only is the narrative story of that era fascinating, the many photographs that Mary uses to supplement the story help to provide additional context to her documentation of this important time in our lives. … I highly recommend this book to people interested in learning more about the Asian American Movement!”

Uyematsu Kao doesn’t see Rockin’ the Boat as a call to action. Her book aims to show how the 1970s Asian American movement worked to raise consciousness about U.S. imperialism, which she views as still ever-present today. Although the book’s events took place decades ago, she sees the fight against U.S. imperialism as the connecting link between the Asian American movement and present-day movements.

“We’re fighting the same enemy… The government is basically representing the interests of the U.S. imperialism, and so it’s a continuation of the same struggle.”

In her epilogue, Uyematsu Kao writes, “The Asian Movement was my beginning on a different path away from the mainstream. I learned how to think outside the box. I learned how to identify and question U.S. propaganda. … I wish to use the past to illustrate our understanding of what is happening today. It is my way to honor all those who took part and created an exciting and powerful movement.”

As a special to AsAmNews readers, you may purchase a copy directly from Uyematsu Kao for $30 (that includes shipping) by emailing rockin dot kao20 at gmail dot com. Autographed copies available on request.

AsAmNews has Asian America in its heart. We’re an all-volunteer effort of dedicated staff and interns. Check out our new Instagram account. Go to our Twitter feed and Facebook page for more content. Please consider interning, joining our staff, or making a financial contribution to support us.