By David Hosley

A California State Assembly hearing may breathe new life to the lost Japantown in Sacramento and other communities cut off by freeways and redevelopment.

The session at 1 p.m., chaired by Assembly member David Alvarez (D-San Diego), will explore the impact of freeway construction in California and how it has disrupted communities.

Four members of the Reclaim Sacramento Japantown initiative will also be speaking about the history of the West End that was decimated by redevelopment and new highways in the 1950’s and 60’s.

Michelle Huey, Joshua Kaizuka, Priscilla Ouchida and Jim Tabuchi are among those making remarks about the West End’s history at the legislative hearing. They are part of about a dozen community leaders with an interest in the historic Japanese neighborhood that covered about eight blocks from 3rd and 5th between L and O Streets in Sacramento almost a century ago.

Tabuchi, who is facilitating planning for Reclaim Sacramento Japantown tells AsAmNews that they want to engage with people from all communities that once lived in western part of the city—Chinese, Filipino, LatinX and African American. “This is more than memorial,” he adds. “It should be productive for the whole community.”

The hearing about disruption of community is timely, in that the state legislature is now pondering reparations for African American residents in California who are descended from slaves. Japanese Americans have the collective experience of having secured compensation for violation of civil rights through legislation whose authors included Sacramento Congressman Robert Matsui, and signed into law by President Ronald Reagan, California’s former governor.

How Sacramento Japantown came to be

The initial Japanese immigrants to California include several who passed through Sacramento. The Wakamatsu Tea and Silk Colony settlers continued on to farm near the gold discovery site at Coloma in 1869. An ambassadorial delegation to Washington D.C. disembarked in San Francisco in January 1872 and took trains across the country in the middle of winter. Some members of the colony stayed in California after it disbanded.

But immigration from Japan began in earnest with the Meiji reformations emphasizing industrial development in the 1880’s, which depressed agricultural sections of the country economically. Farm workers in southern Japan especially sought opportunities in American states bordering the Pacific, California chief among them.

The Issei, the first generation of Japanese to come to the region, were almost all young men. Finding jobs in Walnut Grove, Isleton, Florin, Loomis, Penryn and Auburn, they needed goods and services and Sacramento had them to offer. A grocery store catering primarily to Japanese was built in 1893 not far from Chinatown. As the Issei community grew, a Japantown developed in the 1900’s from 2nd to 5th Streets, adjacent to where the Sacramento Kings arena is today. A photo of the businesses from the 1910 on Third Street between L and M Streets (M was renamed Capitol Avenue in 1928) shows: Ohira Express Shipping, Higoya Boarding House, Ariake Dry Goods, Kitaura Taylor, Mikado Fish Market and Ishii’s Eagle Drugs.

The peak of Japanese immigration was the 1910’s, when matchmaking resulted in men returning to Japan to find a bride,or exchanging photos and meeting their intended as strangers at ports from Seattle to San Francisco and Los Angeles. There is one account of a group wedding, with the couples celebrating their vows by shaking hands. Young families were soon to follow, but government measures later restricted the flow of brides, and then Japanese immigrants in general in 1925.

There were also restrictions on owning property. In 1913, the California legislature enacted the Alien Land Law, primarily aimed at restricting ownership of land by Japanese immigrants, but also applying to Koreans, Chinese, and other of Asian heritage. The state body tightened restrictions in 1920 and again in 1923. California laws were copied, in whole or in part, in other states in the west but as far away as Florida. In 1923 the U.S. Supreme Court reviewed these laws and upheld every one of them.

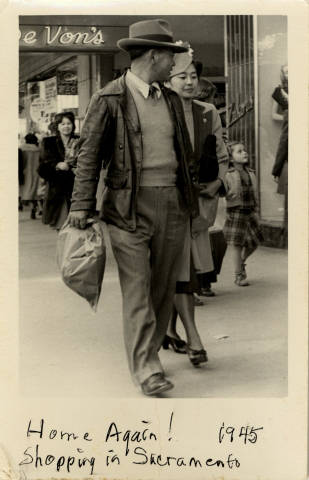

On weekends in the 1930’s Sacramento’s downtown was flush with Japanese speaking visitors who’d come into the city to shop, eat, drink and cavort. The Nihonmachi neighborhood had expanded to the south, with a core presence from L to P Streets, and more Japanese businesses, homes and rooming houses on adjacent blocks. The north end of Japantown was just a block from some of the prominent stores on K Street, just as Weinstock and Lubin, W.T. Grant and Montgomery Ward, which were also destinations for visitors from surrounding towns.

Sacramento was different from most Japantowns in California. It was in a large city as were the Japantowns of San Francisco, San Jose and Los Angeles. But it was uniquely just blocks from California’s Capitol where laws were being drafted and debated that fundamentally were changing their lives. Less formal, but nonetheless impactful, Sacramento Issei and Nisei were often denied access to health care and were not allowed in public swimming pools, a discrimination also applied to African Americans. The response to lack of medical facilities was to build their own Oriental Hospital.

Japantown also had its own lawyers. The first was Walter Tsukamoto, who came with his family from Hawaii to Sacramento as a baby in the early 1900’s. Tsukamoto attended Sacramento High School and then the University of California in Berkeley, where he was the first Japanese American to be in the Army Reserve Officer Training Corps. He graduated from Boalt Hall at Cal and set up his practice in Sacramento’s Japantown in 1929. He helped start the Sacramento Japanese American Citizens League chapter in 1931 and lobbied against anti-Asian legislation. He later became the national JACL president, working to halt anti-Japanese federal measures.

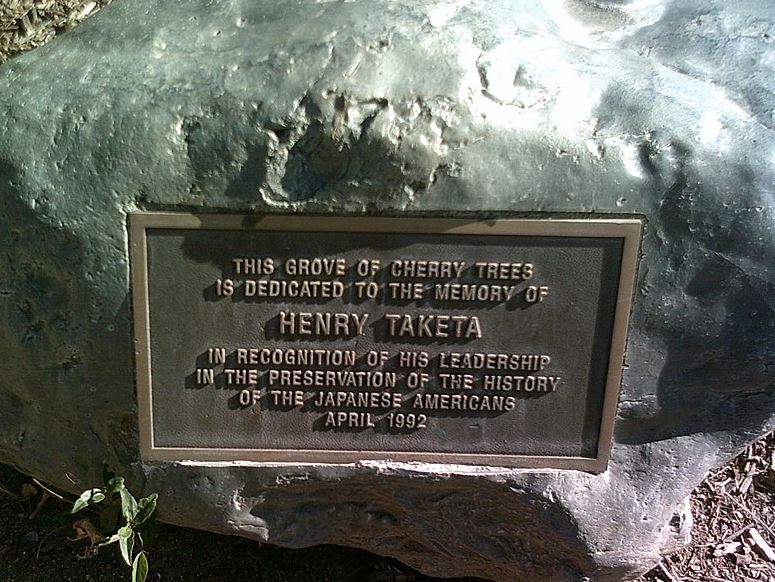

Henry Taketa established his law practice in late 1936, having been born near Florin in 1913. His father had emigrated in 1900, with his mother following in 1907. In addition to farming, his father sold insurance, and the family moved to 5th and N Street in 1918 to improve business opportunities. In an oral history from 1984, Taketa recalls the Chinese community was centered around I and J Streets, with Italian immigrants around South Side Park and Portuguese on the other side of the railroad tracks.

After graduation from Sacramento High, Taketa attended Sacramento Junior College and learned he could go directly from there to Hastings College of the Law. Once he passed the bar, Taketa opened a general practice which only had Japanese clients. Taketa was also a co-founder of the local JACL chapter.

Sacramento was the site of sumo, basketball and baseball competitions, including youth leagues and tournaments for teams representing towns with significant Japanese populations. Its Japantown hosted a range of religious denominations, which had their own series of conferences and gatherings augmenting religious services.

One thing the young people of Japantown had in common was Lincoln School. It was at 418 P Street, where CalPERS has a huge office building today. The majority of students were Asian. Two prominent community leaders were asked a few decades ago about collaboration between Chinese American and Japanese Americans on construction of an Asian Senior Center in Sacramento where Asian food and holidays are celebrated. “Oh, we got all the competition out on the playground at Lincoln School” said Toko Fujii, chuckling with Sun G. Wong.

Although the legislature had passed a law allowing separate schools, Sacramento’s were not officially segregated, although deed restrictions and social norms were effective in limiting where African American, Asian American and LatinX students received their educations.

Many Japanese American children in Sacramento also had additional studies after their elementary school classes ended each weekday. They were sent by parents to after-school classes at a Japanese language school. Textbooks printed in Japan were used, mostly to teach language and cultural norms. Students remember the teachers being strict. Parents paid tuition for the additional instruction.

The 1930’s were a high point for Japantown in terms of population, about 3,000, and businesses, about 475. Even though the Great Depression spanned the decade, Sacramento’s Japanese community benefitted from being in the heart of California’s Central Valley. Money was in short supply, but crops were grown and labor needed to plant, tend, and harvest them.

Henry Taketa recalled his father’s insurance business was hit hard, and farmers would be forced to dump some of what they’d grown to keep prices up.

The goods, services and affordable housing available in Japantown were magnets for Issei and their families, as were the railroad, bus, and river travel hubs. Sacramento was also helped by being the center of state government.

“I think there was a great deal of trying to help each other,” said Taketa. “There was, I think, mutual assistance of a kind built into the Japanese American society of the time.”

Japantown residents had to look only a few blocks north to find many worse off than they were. Jibboom Street northwest of the rail yards became one of several Hoovervilles in Sacramento, attracting refugees from the Great Plains who hoped the agricultural economy of California would provide work to help them survive the economic plague that lasted a dozen years and didn’t really end until World War II.

Pearl Harbor, Walerga and Tule Lake

Japan’s aggression in Manchuria starting in 1931 and the depravity in Nanking in 1937 had reverberations in California’s Nihonmachis. They worried about the spector of a broader conflict. Most residents of Sacramento’s Japantown had close relatives in Japan and it was not uncommon to send children for school or return to care for an aging or ill family member. When Pearl Harbor was bombed at the end of 1941, the opportunity to return to California vanished.

It could be argued that the beginning of the decimation of Sacramento’s Japantown began on December 7, 1941, for it was never the same after that date. Travel was almost immediately restricted for residents of Japanese ancestry along the Pacific Coast. Some left for the interior of California. Others sought safety further east, but anti-Japanese sentiment already present in California laws and culture was fed by rumors and inaccurate reporting.

Henry Taketa and his wife Sally had just moved into a new home at 23rd and S Streets late on December 6th. They were having breakfast the next morning when his mother-in-law called and said to listen to the radio. “I told Sally, beware—we have to be on our guard because it looks to me like as part of our citizenship, we might be uprooted.”

On February19, 1942, President Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066, which set in motion removal of all those deemed a threat to commit espionage and sabotage in time of war. The three Pacific states were divided into zones for enforcement of the restrictions. Then, Japanese families were asked to relocate voluntarily from a handful of areas. About seven percent did.

Congress passed Public Law 503 on March 21, 1942 which made failure to comply punishable by imprisonment and a fine. Then under the authority of the executive order, on March 29, 1942, a proclamation began a cycle of forced assembly and incarceration of Japanese and Japanese Americans. By April, Japantown had grown by hundreds who had fled from surrounding communities, hoping that they could go to the same destinations as family or friends.

Sacramento Japantown residents were given less than a week to store or dispose of their possessions and property, if they held ownership. In May, they got orders to gather at Memorial Auditorium on the other side of the Capitol. They were initially held at the Walerga Assembly Center, also known as the Sacramento Assembly Center, which had most recently housed migrant laborers.

Little went well about preparing the site. It had rained a good deal that spring and the grounds were muddy. The new barracks were built on uneven ground, and so hastily that there were gaps in the floorboards. It wasn’t really ready for the first buses that arrived on May 6, 1942. By the end of the month, there were 4,739 imprisoned at Walerga and the government had brought in help to retrofit the substandard construction.

Mosquitoes bedeviled the new occupants, and flies compromised preparation of food. Pit toilets were built, also attracting flies. They weren’t deep enough and soon filled up. There was tension between the men running the facility and the Japanese being held there, but there was also bad blood between the prisoners. The center was open for 52 days, but the majority were there a shorter period. Starting June 15, in groups of about 500, almost everyone incarcerated at Walerga was put on trains bound north for Tule Lake Relocation Center.

In short, Tule Lake was a disaster. They Japanese and Japanese Americans forced to live in the remote area just south of the Oregon border came from big cities as well as rural towns and didn’t mix well. The young guys from Los Angeles were deemed especially problematic. Almost 30,000 were held in the high semi-desert between 1942 and 1946, with the peak population being just under 19,000.

Capitol Mall Project

Plans to dramatically change the area between the Capitol and Sacramento River had actually started just as former Japanese and Japanese American residents were returning to the city. The City Planning Commission hired two planners to study future government construction along Capitol Avenue. Before the war, any expansion of places for state workers had to be east or south of Capitol Park.

City planner Glenn Hall followed up the initial report with a document that suggested height limits and a 40 foot setback for any new state structure on Capitol Avenue between the river and Capitol Park. He also recommended establishment of a Capitol Mall Committee to focus resources on further plans. The city council adopted his vision and established a City Improvement District which included the heart of Japantown.

The next big step came in 1950, when the council designated a 60-block area as “blighted” and called it Redevelopment Area 1. Two more adjacent areas of the West End would be similarly selected as needing redevelopment. By 1953, there was a plan sketched out showing a mix of blocks devoted to commercial space, private and public housing where Japantown still stood.

Taketa and other Japanese American community leaders opposed the plans. ”Oh, there was opposition,” Taketa later said. “We opposed it on the basis that we went through evacuation or relocation once, and we know the hardship more than anybody else.” He expressed special concern about the Issei, the pioneers who came in the first wave of Japanese immigration. “Once they moved, once they had given up what they had, they would be too old to start all over again. So it would be a demise of what we called Japantown.”

Sacramento was hardly alone in wanting to modernize its urban core. It wasn’t even singular in wanting to improve the impression given as motorists crossed into the state capitol from Tower Bridge. The designers of the Capitol Building had wanted a grand entrance similar what Washington, D.C. and many other state capitals had similar wishes. Redevelopment became a national phenomenon after World War II, with cities experiencing unprecedented growth while population growth and improved highway systems also fueled suburban flight from decaying city centers.

Federal legislation in 1947 changed Title 1, which could provide funding, and two Housing Acts in 1949 and 1951 provided further assistance at the regional and local levels, complemented by the Highway Act of 1956.

A CSU Sacramento graduate student, Ken Lastufka, studied the redevelopment of Sacramento’s West End in the 1980’s. He looked at the data that was causing city officials to seek redevelopment. He found the area had a large population of farm workers, and 20 percent service workers and 20 percent skilled and unskilled industrial laborers. In 1950, he reported, the median income for West End’s work force was 40% of the median income for other workers in the city.

Two other factors were racial restrictions in more affluent neighborhoods, which tended to force lower income non-whites into areas like the West End. Property values were lower in the areas designated for redevelopment in Sacramento, with 75% of dwelling units built prior to 1919. Both affected the city’s tax revenues, and municipal costs were elevated because police and fire responded more often to that part of town.

In 1950, the West End generated 12% of all tax revenues for Sacramento. It received 24% of fire department services, 41% of police costs, and 50% of the city’s health services budget.

The city council was responsible for the financial well-being of the government. It wasn’t a close call. But it took years for the plans to become reality, through the later 50’s and into the 60’s.

“By 1970,” Latufka concluded, “the low income population and small businesses that it once harbored were gone, replaced by tall buildings and day workers. But the impact of renewal went beyond the borders of West End redevelopment projects. For one, over three-quarters of all former residents relocated into just four areas.”

He went on to observe that each group now dominated the new places they went, and brought their socio-economic characteristics with them. Sacramento officials had managed to increase segregation and lowered the property values of four neighborhoods by decimating a diverse one. “Redevelopment, in effect, transferred the social and economic problems of the West End to other parts of the city.”

The new Capitol Mall was dedicated in December, 1968

Renaissance Of Sorts

Attorney Robert Mukai started working in downtown Sacramento a few years later in 1973. “I was aware of it having remnants of Japantown,” he related to AsAmNews. “It’s ironic that at the base of the Capitol you had this heavily ethnic area and in the name of urban renewal it was cleaned up. My impression was also that the building of I-5 and the W-X freeway had cut downtown off from the rest of the community.”

Mukai soon got to know the legacy Japanese businesses, and newer ones that had sprung up. A favorite was Fuji Restaurant on Broadway near the Buddhist Church. The original family business closed years ago, but new restaurant owners Russell Okubo and Kevin Oto are honoring the beloved eatery by including many traditional Japanese American dishes on its menu, including Sesame Chicken. They also received permission to call it by the same name.

There are other echoes of Japantown not far away from what was redeveloped. Some businesses relocated to 10th Street near Southside Park—a drug store, one selling shoes, another appliances. Today you can find Royal Louis Florist, Osaka-Ya Confectionary, and Binchoyaki Izakaya Dining on 10th between V and W Streets.

Osaka-Ya often has lines out the door for its fresh manju and mochi and other comfort food. In hot Sacramento summers, its shaved ice is popular. Orders for its confections also come from far away fresh manju is a rarity in northern California now.

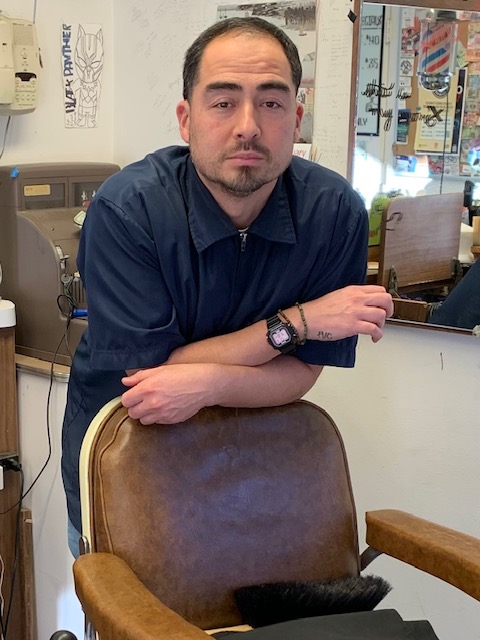

There is one more block that’s a destination for those interested in Japantown’s past, but also its future. It’s the 1500 block of 4th Street, and its buildings are more recent. That’s where you’ll find Nisei Barber Shop, whose owner is Cory Umeza. His grandfather Jack founded the business when he returned from military service after the war. He had distinguished career in the Army, joining up in November, 1941 and earning a Bronze Star medal for heroism in the Philippines. The G.I. Bill to pay for barber school.

As a child, Cory spent time watching customers get a trim, and maybe a shave. Eventually, he teamed up to split the work as Jack continued to cut hair until he was 92. His grandfather passed away in 2013. Ironically, a good part of Nisei Barber Shop’s clientele today are state employees from the towering office buildings that replaced Japantown.

If customers want to know more about the neighborhood, Cory only has to point down the block, where the Nisei Veterans of Foreign Wars Post 8985 sits. It was designated as a historic landmark on the Sacramento Register of Historic and Cultural Resources in 2021.

The building was constructed in 1952 for African American businessman Phelix Flowers and his spouse, Minnie. It was a modern design and intended to be a restaurant with a rooftop garden. The Flower Garden restaurant had meeting space, and hosted NAACP gatherings, and the African American Elks chapter.

The VFW members had been looking for a place to host its activities and archives, and when the restaurant closed several years later the Japanese American Citizens League purchased it for the post, and it still home to the VFW. On the street side of its parking lot is a two-sided history wall detailing the saga of Sacramento’s Japantown and its residents.

Cory Umezu is grateful that Japantown is remembered, telling AsAmNews “I appreciate that people are telling the history of this place.” He also is looking to the future. His children are Gosei—fifth generation Japanese Americans.

The legislative hearing will be held at the State Capitol Thursday by the Assembly Select Committee on Reconnecting Communities.

AsAmNews is published by the non-profit, Asian American Media Inc.

We’re now on BlueSky. You can now keep up with the latest AAPI news there and on Instagram, TikTok, Facebook, YouTube and X.

We are supported by generous donations from our readers and by such charitable foundations as the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

You can make your tax-deductible donations here via credit card, debit card, Apple Pay, Google Pay, PayPal and Venmo. Stock donations and donations via DAFs are also welcomed.