By David Hosley

(This is part of our ongoing series, Lost Kinjo- a look at the more than 40 Japanese communities that disappeared after World War II. It is supported by funding from the California Public Library Civil Liberties Project and the Takahashi Family Foundation.)

This spring marks the 100th anniversary of the U.S. Immigration Act of 1924, which was primarily aimed at halting Japanese newcomers. The Act’s impact greatly affected the new city of Livingston in California’s Heartland, a place that later became the self-proclaimed Sweet Potato Capital of the World.

Before Livingston became incorporated in 1922, a visionary entrepreneur from Japan created a colony of settlers in the area and set it up so the immigrants who lived there avoided another great injustice—a series of California Alien Land Laws inaugurated in 1913.

Man With A Grand Plan

It’s likely that a small number of Japanese immigrants came to northern Merced County prior to Kyutaro Abiko. But it was the imagination and promotional genius of Abiko that greatly expanded the first-generation Issei presence in Livingston and several nearby farm towns.

Abiko was among the early Japanese settlers in California, arriving in San Francisco in 1885. He became a farm laborer, and then a contractor providing workers to the fast-growing California agricultural sector. He was also interested in communications and started a Japanese language newspaper in San Francisco, the Nichibei Shimbum, in 1899. Abiko then founded another company, the Japanese American Industrial Corporation, in 1902. It became one of the largest labor contracting agencies in California.

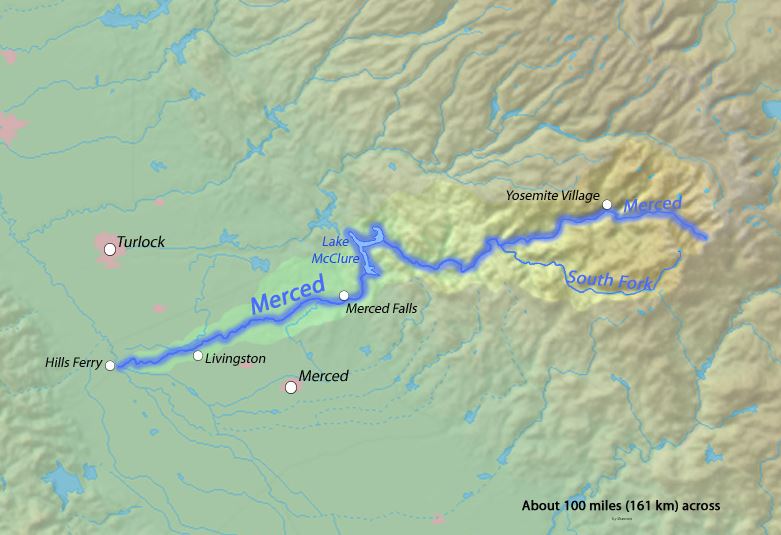

As his enterprises grew Abiko observed the Issei community, which was almost entirely composed of young men from the southern part of Japan. A Christian convert, he became concerned that too many Japanese immigrants were living dissolute lives in big cities on the West Coast. Abiko became convinced they would be better off living in farming communities. So he started to look for an opportunity to make it so. After some scouting trips, in 1904 Abiko purchased 3,000 acres in northern Merced County. Subdivisions were created at $35 an acre, usually in 40-acre parcels, with bank financing available over five years.

It wasn’t particularly attractive land by most agricultural standards, save one key factor. The sandy soil was the eons old result of the Merced River with headwaters in Yosemite that ran through the Great Valley to the San Joaquin. That river made all the difference. The colony would have a water supply that would irrigate fields aplenty. Japanese farmers would grow crops where others thought there was no chance.

From Idea To Colony

Abiko named his initial purchase Yamato Colony and set out to fill it with sojourners. The new venture was advertised in his newspaper, but also through his labor network by word of mouth and letters home to Japan. The men who responded were looking for a better life, and the expectation of most was that they would save a good part of their wages and be able to return to Japan to marry. Abiko and his companies could market the colony, paint a picture of a better life, connect immigrants to jobs, sell tools and clothing needed to do the work, and in some cases find them a place to live until they got their feet on the ground.

Immigration from Japan continued growing. By 1885, Japan was allowing more young men to leave for America. Some of them brought funds to invest or saved enough by working as laborers to buy small farms, usually 20 acres.

In an oral history, Sherman Kishi provides a case in point. His father Shozo came by boat to Seattle and continued to northern California where he was a farm worker. Sometime after the famous earthquake had shaken northern California, Shozo Kishi acquired property in Yamato Colony.

By 1910, there were more than two dozen new landowners in the colony, mostly Issei from Wakayama Province. The newcomers relied on Livingston merchants for supplies. After the land was prepared for the kinds of crops the Japanese wanted to grow— mostly grapes, tomatoes, asparagus, melons and eggplants—Abiko’s dreamland attracted a continuing steam of Japanese men and women. One of them was Shozo Kishi’s picture bride Chiyoko Hashizume in 1910.

Trains took their crops to markets as far away as Los Angeles, Portland, Seattle and points east. The unique elements of the Yamato Colony’s Livingston Orchard and Vineyard Corporation allowed farmers to avoid the brunt of anti-Asian legislation in California, which forbid Issei from owning property (more on this later). There was little sharecropping or use of rental systems that kept so many Japanese elsewhere in the Golden State from building capital.

While cooperatives like a farmer’s association were started mostly to provide price breaks on equipment and supplies and to jointly process products and sell them, the growing Japanese community also made an important decision about competition in other areas of the local economy. They supported, rather than competed, with Livingston’s grocers, mercantiles, drug stores and restaurants. The Issei focused on agriculture while becoming an important revenue source for local merchants. Crops that took longer to develop, such as grape vines and fruit trees, added diversity to the staples of northern Merced County agriculture.

Two Communities—One Town

There had been a settlement in northern Merced County since the 1870’s, but it was unincorporated for the next 50 years. It was situated on ancestral lands that had been home to Yokuts for at least ten thousand years, specifically the Ausumne band. They had been driven off by the Spanish, starting before the Gold Rush and were all but absent by the time Japanese arrived. The leader of a wagon train in 1862, Daniel Chedester from Iowa, had terminated his trip in Stockton, and then went on to northern Merced County. Chedester acquired 1,500 acres of land in the Livingston area, where he diverted water from the Merced River and raised wheat, fruit and livestock, including hogs.

Another settler, Edward Jerome Olds, came to the area in late 1871 and opened a store. He applied for a post office the next year and added it to his operation. An irrigation system was begun in the area, and then Olds mapped out a new town and filed the plan at the urging of another newcomer, William Jackson Little. The map showed 80 lots, which were intended for sale at one dollar each. Livingston lost the “e” in its name at some point and sought to be named the county seat. The City of Merced won the election, and the runner up didn’t prosper. In 1883, Little sold his Livingston holdings, and most of the lots were returned to growing wheat.

Ironically, immigration from Japan had been aided considerably by the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882, which shut off a key source of farm laborers to the Central Valley. By 1885, Japan was allowing more young men to leave for America. Some of them brought funds to invest or saved enough by working as laborers to buy small farms, usually 20 acres.

In 1900, 1% of the farmland in California was owned by Japanese. Abiko had added to that number by starting the Yamato Colony near Livingston which was followed by extensions east in Cressey and Cortez. By buying land in the San Joaquin Valley, Abiko provided an alternative to the hurly-burly of San Francisco. Access to capital, farm labor and media holdings that reached throughout the Pacific Coast all came together in a great social experiment.

In an oral history done in 1999, Sam Maeda recalls some of the first Japanese to come to Livingston were the Tanaka, Okuye, Ueda, Okuda and Kishi families. Maeda’s parents had lived in Winters and San Francisco and the earthquake got them thinking about the Yamato Colony, even though they’d never farmed before.

Seinosuke Okuye’s farm was a landing spot for dozens of newcomers. Okuye had come to Livingston in 1907, and his farm was a place young Japanese could get a foothold that might lead to ownership. The newcomers started out as field hands and learned planting and irrigation skills while hopefully saving part of their pay. Okuye’s farm eventually had 13 houses for the immigrant workers and played a catalytic role in the colony’s advancement.

Skirting The Alien Land Law

Without knowing it, Kyutaro Abiko provided a safeguard against a potential death knell for the long-term growth of the Japanese American community. The California Alien Land Law of 1913 restricted immigrant purchase of property. General in language, it was aimed directly at the first generation of Japanese immigrants. It was copied by more than a dozen other states and set the foundation of intolerance that led to incarceration of more than 120,000 after Pearl Harbor.

But when the legislation became law, most of the Issei in the Livingston area already had deeds in hand and a model that could be adapted by others. The Issei married and started to build community infrastructure. In 1913, the Livingston Cooperative Society was started, with a purpose of improving yields and marketing crops. They then added the Livingston Church of Christ in 1917 with more than 40 charter worshippers. But the end of the decade, there were more than 200 Japanese living in the area. The church started a kindergarten to teach English to youngsters so they could succeed in the local schools.

Not Wanted Here

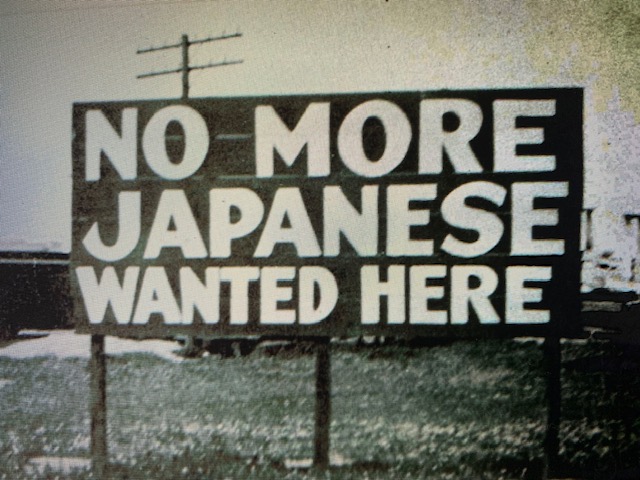

The growth of the Japanese colony was alarming to some of the Caucasian residents. It was not an isolated response, as there had been several so-called “Gentlemen’s Agreements” between the Japanese and American governments to limit immigration from Japan since the turn of the century.

The Sacramento Union headlined a July 22, 1920 article “Bitter Feelings Discovered in Towns of San Joaquin” which reported on a Congressional fact-finding trip the day before that stopped in Livingston.

The article reported the townspeople had taken down the “No Japs Wanted” signs at entry points. But it quoted farmer Lewis D. Love’s warning: “If more Japanese come around there would be trouble.” Abiko was accused of bringing Japanese to the area “by devious means.” The Union report also noted that Livingston Chronicle editor Elbert G. Adams had forged an agreement with Japanese community leaders that further newcomers would be discouraged.

Adams was 30 years old at the time, and also was the head of the Anti-Japanese Association of Merced County. Born in Colorado, his family had come to California when he was three and traced their ancestry to John and John Quincy Adams. Elbert Adams’ schooling took place in Santa Rosa and Auburn. At 16, he got a job writing for the Sacramento Star, and held several other jobs in journalism before buying the Chronicle in 1915.

Immigration Act of 1924

At the federal level, legislation had been introduced in 1920 to put a quota system in place to limit immigration to the United States but it did not get Woodrow Wilson’s approval. But new president Warren Harding called a special session of Congress and signed it into law. The next year the quota law was extended for another two years.

Immigration remained a hot topic, and Congress again drafted legislation in 1924. This time the formula for quotas was changed to allow fewer immigrants, and the census used to calculate the number from each country was moved back to the 1890 count. And no one could immigrate if they were an alien who was ineligible for citizenship based on race or nationality because 1924 law incorporated the existing Asian Exclusion Act and the National Origins Act.

As the bill worked its way through Congress, an editorial ran in the center of the Livingston Chronicle front page on May 2, 1924. It wasn’t labeled as such and there was no byline. “Our West Coast and the Japanese” was the headline. “We should remain distinct, side by side, in harmony and friendship,” was the theme. “The Japanese are economically our superiors…they can supplement us on the soil, which means they can eventually supplant us entirely if we take them into our country.” The opinion piece concluded “the people of the Pacific Coast see their finish if oriental races are admitted.”

Three weeks later, Congress enacted the Johnson-Reed immigration bill and President Harding signed it on the south lawn of the White House. The new law violated the Gentlemen’s Agreements and the Japanese government protested, to no avail. The adopted measure created a new status for some immigrants: undocumented. It also inaugurated a new policing force, named the Border Patrol. Excluded from quotas were people from the Western Hemisphere. The flow of Issei to America had been shut off more tightly than an irrigation ditch to a field. The relationship between the U.S. and Japan, already problematic, further eroded as a result.

Later in 1924, the Livingston Chronicle editor and head of the Anti-Japanese Association of Merced County ran as a Democrat for the California State Assembly and won. Adams would be re-elected twice more in 1926 and 1928 before unsuccessfully running for State Senate.

Depression Era Japanese American Baby Boom

If the first generation of Japanese immigrants to Livingston was largely male, new brides in the 1910’s meant a lot of Japanese American children came along in short order. The school-age population grew rapidly just in time for the Depression.

Sherman Kishi was born in 1925, and grew up going to Livingston schools. “For us, it didn’t seem that difficult,” he recalled in an oral history interview. “But it must have been. You don’t realize you’re poor. We had enough food to eat all the time. It just centered around the community.”

There were advantages to living on a farm, where you could grow a lot of what you needed to stay healthy, and barter for some of the rest. He recalls hundreds of Japanese American neighbors lining up to pursue rabbits which were decimating young grape shoots in the fields. Rabbit stew was a staple in those days.

Frances (Fran) Yuge Kirihara, in a 1992 oral history, remembers that cash was hard to come by. “We didn’t have much money to buy things at the store,” she said. “So the men got a big net and got fish out of the irrigation canal. We all raised our own vegetables.” Bread was hard to pay for, so Fran’s mother sent her children to school with rice balls instead of sandwiches for lunch.

The older of the second generation, the Nisei Japanese Americans, were teens during the Depression and attended the new Livingston High School. There were farm kids and town teens, and they didn’t mix a lot except in the classroom. For one thing, most of those living on farms had work to do before and after school. An odd ramification is that many of them drove to school because they learned to guide field equipment as soon as they could see over, or through, a steering wheel.

Fran Kirihara recounted that her father couldn’t make his payments in 1932 and lost his property. He also borrowed money from a prominent Caucasian farmer, and from family friends. It was paid back in the fall once harvest had been completed. She started at Livingston High in 1934 but before school she had to feed the chickens and, in season, cut asparagus and sometimes deliver it to customers.

After school and on weekends she would harvest and pack peaches and cut apricots for drying on wooden flats. She also became quite good at putting together wooden crates. Sometimes she worked for other farmers. Any money earned during the summer would go to buying school clothes. Things got better for the Kirihara’s by 1938, and they got a new car. It came with a set of dishes, which apparently was a common incentive at the time. Census records show a 48-hour work week was common, and more during harvest.

Social life was more often around church, and the Livingston Japanese Methodist Church drew members from Cressey and Cortez, too. Regional church gatherings got the young people out of Merced County, and they went for conferences as far as the Bay Area and Los Angeles. Baseball, basketball and teams from Livingston competed against teams from Stockton, Salinas and as far away as San Francisco.

Racism remained a part of life in Merced County. Fran Kirihara recalls that after she graduated from Livingston High in 1938, the principal was terminated. It was commonly

thought that his firing was due to a Japanese American, often a female, having the highest-grade point average and thus named valedictorian year after year. The successor changed the commencement speaker to the student body president.

Fred Kishi, Sherman’s brother, excelled in the classroom at Livingston High and he was also an accomplished athlete in basketball and track, sports that he’d played in Japanese youth contests growing up. The letterman also played football at 120 pounds, and he and his Livingston High lightweight team were the league champions. Fred was accepted at the University of California in Berkeley, started classes in 1939, and made the track team.

Common business interests also bound the community together, including cooperatives. Tom Nakashima remembered 125 families in the Yamato Colony as 1940 began. He said 13,000 acres were planted in sweet potatoes in the county. It was just a fraction of the estimated 68 million dollars’ worth of land that Japanese and Japanese Americans owned in California in 1941.

Pearl Harbor Changed Everything

Sherman Kishi was playing tennis at Livingston High on Sunday morning, December 7th, with Lilly Hamaguchi and James Kaji. A car drove up and its occupants started yelling insults at them. The teenagers went home and learned of the attacks in Hawaii. With the U.S. at war, uncertainty permeated California, which was thought to be vulnerable to attack because of its location on the Pacific rim. Anti-Japanese sentiment was more openly expressed. Rumors spread that there would be arrests or worse. The government issued restrictions on travel.

At first, it seemed Japanese and Japanese Americans in the interior of the state, like the Central Valley, were free to move about. But then the boundaries changed and inland Issei and Nisei residents could no longer go to San Francisco and other coastal areas. Livingston was in Zone 2; the coast was Zone 1. Some students from northern Merced County who were in college in the Bay Area returned home, while other young men considered joining the Army. One Livingston family moved to Denver, where they had relatives. From that moment in time, the dislocation of people of Japanese heritage accelerated in America.

Fran Kirihara was studying in the Bay Area on December 7th. Two days after Pearl Harbor, the nursing student was told to leave and go home. “None of us questioned if it was the right thing or the wrong thing.” She arrived back home on December 10th. “Then we got a curfew, we had to be in the house by dark. We didn’t challenge them. We all had blackout windows. We didn’t know what was ahead of us.”

In the spring, posters mounted on phone poles in Livingston announced Executive Order 9066, which directed the mass incarceration of Japanese Americans along the American west coast. The deadline to report to the region’s assembly center at the Merced County Fairgrounds was May 13th.

Protecting Their Land

Dozens of Yamato Colony farmers had used the time between the executive order and reporting date wisely. In a 2002 oral history, Frank Suzuki talks about violating the travel restriction to go to the San Francisco office of the Pacific Fruit Exchange. The exchange distributed the products of Central Valley farmers nationally, and Suzuki along with Kenji Minabe and several members of the Kishi family, proposed that PFE consider managing their farms while they were incarcerated. Suzuki reports the company’s executives were shocked to see them but agreed to consider the notion. The carload of farmers returned to Merced County without incident, but a few days later were notified that PFE wasn’t interested.

Suzuki’s group turned to leaders of growers associations in nearby towns. “Let’s get together,” Suzuki recalls the thinking, “and maybe the three of us can make it interesting for somebody to take care of the farms.” Now united, the Japanese American farmers of northern Merced County decided to approach trusted business leaders about forming an organization to protect their interests. A Lodi lawyer drafted the establishing documents. Hugh Griswold, a Republican lawyer from Merced who had represented some of the farmers, agreed to chair a board of Caucasian trustees. The board in turn hired Gus Momberg, a former banker who also knew the dynamics of agriculture, to receive power of attorney to operate and, in some cases, lease farms owned by those imprisoned.

Suzuki had a good feeling about Momberg. “I happened to work for him when I was going to high school. I used to disc some of his orchards and vineyards, so we knew Gus.” There was some back and forth before Momberg came aboard. He wanted one per cent of the net operations of the more than 100 farms the trust would oversee. He also wanted one per cent of the gross, and three per cent of the trust’s profits each year. To Suzuki, it would be money well spent, and the others who worked on its formation were all in as well.

Some of the area’s farmers had panicked and sold their acreage for next to nothing. By coming up with a way to protect the titles of most Japanese and Japanese American farms, the Yamato Colony farm families would ultimately find security.

But in the moment, Pearl Harbor was shocking. “We faced discrimination from the first grade, “ Noburu Hashimoto recalled in an oral history interview. “But they didn’t know what they were talking about. Then it got really bad after Pearl Harbor. I was a sophomore at Livingston High, and some of your friends just ignored you. It kind of hurt your feelings. All of a sudden, they’re not your friends anymore.”

Hashimoto was spit on by a classmate and subjected to ethnic slurs. Next came incarceration. The Suzuki family drove themselves to the check in at American Legion Hall in Merced. Their new car had been sold at a loss with the proviso they’d use it one last time. They unloaded possessions they’d packed and left the key in the ignition for the new owner. A bus shuttled them a short distance to a holding facility.

Assembled In Merced

The Merced Assembly Center had been thrown together on the site of the county fair. Inexperienced teens were part of the carpentry crew, and some of the construction materials were substandard. The Merced County families were incarcerated with residents of Walnut Grove, Stockton, and others from Sutter and Yuba Counties.

The new buildings were 20 by 100 feet, with each family having a 20×20 foot space, divided only by blankets or sheets. Each building had a lavatory and stoves, with cooking mostly done by the residents.

Some of the high school seniors received diplomas while incarcerated at the fairgrounds. But the only schooling was daycare for younger children, and arts and crafts for adults. Working under Caucasian supervisors, some men became firemen or enforced the restrictions on moving freely after dark.

It was miserably hot that summer in Merced. Temperatures regularly reached over a hundred degrees. The prisoners tried to stay in the shade, but sometimes would have sumo contests or talent shows on Saturday night. Noburu Hashimoto remembered the black tarpaper on the buildings attracted the sun’s rays, and the Issei particularly suffered in the heat. The crafts sessions, he said, were held in horse stalls. And everyone knew more permanent prison camps were being built in the interior of the country and they would soon be far from the Central Valley.

Incarcerated In Colorado

Fran Kirihara was one of the first to leave Merced. With training as a nurse, she was selected in late spring for an advance group focused on preparing health care facilities at the Granada War Relocation Center. Called Camp Amache by those held there, it was the largest of the 10 facilities in terms of acreage, but with the smallest number of detainees and fewer buildings. Kirihara’s initial work was setting up facilities for infants and toddlers, including the ordering and then distribution of formula for babies.

In September, 1942, the Livingston contingent and the rest of those assembled at the fairgrounds were moved. “We were all anxious,” Hashimoto recalled. “It was my first time to ride a train. We went down to Bakersfield and then Albuquerque on a slow-moving train with no sleeping berths. The windows and blinds were closed.” Because the prisoner trains had less priority than regular passenger and freight trains, it took three days to cross a third of the country. They were met by military trucks in Amache and carted off to live behind barbed wire.

A Very Different Existence

It took a while to adjust to life at Amache. Prisoners came from a variety of towns and cities. The government had built the block houses quickly and they were often made of green wood which wouldn’t seal. Before long it was cold, and people focused on staying warm, which meant months went by before spring brought better weather. Hashimoto washed dishes in camp for $16 a month.

Almost immediately, some prisoners were released in work parties because much of the Colorado farm labor pool prior to 1942 was now in the military. Able Issei and Nisei males could volunteer to work getting in the local crops almost as soon as they arrived in Colorado. There was appreciation from the local agricultural community for saving the harvest, and a number of Japanese Americans were released to take offers elsewhere in the state, most often in agriculture.

Once Amache opened in late August to the rest of those coming from assembly centers, Kirihara didn’t stay more than a few months. A brother was already in Denver. She got a job there as a housekeeper, and then in December took a position at the University of Colorado. Others were released to attend college or take jobs in the interior of the country. Kirihara actually came back to take care of a sister who had suffered a stroke but left a second time. With assistance from a Quaker organization, the Japanese American Student Relocation Council, about 4,000 of those incarcerated in the 10 facilities were released to attend college. Fred Kishi was one of them, going to the University of Maryland, where he played on the basketball team.

Early in 1943, the government asked for volunteers who would join one of the segregated Army units preparing to fight in Europe. Men with Japanese language skills had the option to join the Military Intelligence Service and serve as interpreters in the Asian theater.

Those who remained at Amache began to settle into routine. Young people went to school, usually taught by outsiders guided by the state curriculum. The medical center was staffed by both outsiders and prisoners. Adult classes were offered, mostly with fellow prisoners as instructors, in a range of topics including art, flower arranging, and other crafts.

The food served was a huge disappointment, as initial menus featured surplus goods such as hot dogs, sauerkraut and cheese sandwiches. Some of those incarcerated in Colorado had brought seeds from home, and camp directors allowed planting in the spring of 1943 that greatly improved daily fare. Musical groups formed, and dances were held along with talent shows. Eventually there were weddings and, sadly, a number of funerals.

Back in northern Merced County, the so-called “Momberg Holdings” board had faithfully kept records and banked the proceeds from the crops and leases. Each year members of the board went to Colorado to brief land owners on their fiscal positions and how the season’s crops were growing. The in-person visits were augmented by letters and telegrams. Frank Suzuki also asked a Portuguese American neighbor to check how his farm was kept up and received periodic updates by mail.

When it became clear early in 1945 that the U.S. government was going to release those who were still incarcerated at Amache, it was decided a few Issei farmers would return first in the spring and prepare for the rest to return.

Starting Over

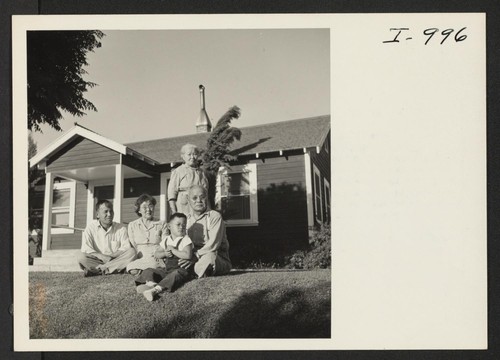

When the bulk of the Livingston families returned home after World War II ended, their farms were a mixed bag. Some had been overseen directly by Gus Momberg and were in generally good shape. But 80% had been leased, and some of those had suffered damage and neglect. Mature fruit trees had died on some properties. Equipment hadn’t been maintained in some cases, or fields kept up. Owners often had to find temporary housing until leases expired.

Frank Suzuki found a cold reception. “The tractor dealer wouldn’t sell me a tire.” He quoted the gas distributor as turning him away, too, by saying “Hell no, I will never serve another Jap.” Suzuki kept at it. “And I went to get a haircut and the barber rushed me out of there.”

Nightriders firing into buildings owned by Japanese farmers became such a problem in northern Merced County the authorities were asked to provide protection. The San Francisco Chronicle reported that four rifle bullets were fired into Chiyoko Kishi’s home. Patti Kishi told AsAmNews her aunt who was in her bedroom was terrified. Fred and Sherman Kishi were both serving in the military at Fort Snelling in Minnesota, and they telegrammed U.S. Interior Secretary Harold Ickes seeking protection for their parents.

Another attack came at the Morimoto residence, with a shot fired about a half hour after the Kishi targeting. Bob Morimoto, whom the Chronicle identified as “an honorably discharged soldier,” and his brother chased the car of the assailants but didn’t catch them. Neither did anyone at the local, state and national level although agencies at all three levels said they were investigating. The Sheriff went to the Merced County Board of Supervisors asking for additional funding to beef up enforcement. It was not granted, and one of the supervisors reportedly made insulting remarks about Japanese not wanted back in the area.

Returnees looked for any work they could get to augment their farm income. Some whose schooling had been interrupted returned to college or trade schools that would provide a profession. Fran Kirihara did some of both. She had finished her nursing degree and got a job at a hospital in Turlock.

Though lasting a handful of years, incarceration took a great toll on the first-generation Issei who had labored for decades in the fields. “They were 55 or maybe 60 years old and they were beaten,” said Kirihara. “They felt there was nothing left to do.”

The post-war years saw a hand-off to the next generation, the Nisei. “Some who got degrees, engineering and the like, came back and maintained farms that their fathers gave to them,” noted Kirihara. “It was kind of a trap.” Other Nisei once home were drawn to better paying work in urban areas, particularly seeking government positions covered by equal opportunity laws. Castle Air Force nearby, for instance, was gearing up for the Cold War.

The scars of discrimination before and during the war remained, even as the baby boom got underway. Suzuki recalled running into Livingston’s mayor, Robin Corbett, in the 1950’s. “He said let’s forget about the old times and be friends again. I replied, you go your way and I’ll go mine.”

Frances Yuge had married James Kirihara after the war. Her husband had bought the family farm from his father and took over the 20 acres. They had a son, and in the early 1950’s, she got a job for the county as a school nurse in Livingston. It was a position she held for 27 years.

Kirihara recalls her school in the 1950’s was “70% White, 10% Hispanic, 5-7% Japanese.” The demographics were changing, in part because the Japanese Americans were selling out. “E. & J. Gallo got bigger on the west side of Livingston,” she recalled. “As the poultry industry began to grow, the farmers sold out to bigger companies.”

Patti Kishi told AsAmNews when she was growing up in the 1950’s and early 60’s social life for the Japanese Americans in the area often revolved around church activities. The Japanese American Citizens League was active again. Japanese youth sports flourished, too, as the third generation, the Sansei, grew up as boomer kids.

Kirihara pegged the biggest shift taking place in 1954 to 1965. When she retired in 1972, her school was “80% Hispanic, 10% White, 10% Other.” Kirihara added “We were seeing more of the children going to college. They weren’t coming back to Livingston.”

Crops evolved as almonds took primacy over peaches and plums, and sweet potatoes grew in popularity. The Livingston Farmers Association membership stayed majority Japanese American through the mid-1970’s. But the brain drain in the Central Valley was well underway by then. “For the third generation, we couldn’t keep them on the farm,” observed Kirihara. “They didn’t come back because they could find good jobs in the (urban) labor pool.” In 1977, the Japanese Methodist Church, so long a pillar of the Japanese community, merged with the original Methodist Church in Livingston.

When asked about the long tail of incarceration, Sherman Kishi said “We never talked to our children about being there” and that, he felt, was unfortunate. He added that he wasn’t really involved in the redress movement that came in the 1980’s. “The biggest weight fell off our shoulders was when we got the letter from the President. Then the check came.” Though former California governor Ronald Reagan signed the 1988 enabling legislation, the apology letter came from President George Bush in 1990. Checks arrived in 1991 to 1993. A total of 82,219 surviving citizens and legal immigrant residents of Japanese ancestry received redress from the federal government.

Sherman Kishi became an unstinting speaker on the history of the Japanese community in Merced County, his wartime experiences at Amache and joining the Military Intelligence Service. He visited countless classrooms, was interviewed at length many times in oral histories, and appeared riding a tractor in a public television documentary seen across the country.

Lasting Impact

The Japanese American community of Livingston has kept its creation story alive through photos, oral histories, scrapbooks and other documents. Some of those archives are on public display at the Livingston Historical Museum on the corner of Main and C Streets. The history of the Yamato Colony is also present in a booklet done for the City of Livingston’s Centennial in 2022.

The Yamato Colony’s Centennial was celebrated in 2007 with a range of community events that included live entertainment, art and historic photography. More than 300 came from far away and nearby to honor the Japanese pioneers and celebrate the three generations of Japanese Americans who have followed them.

Yamato Colony was commemorated in 1989 with the naming of a new elementary school in 1989. Today Yamato Colony Elementary has a student body that is primarily LatinX— 13% Asian or Pacific Islander, 1% Black, 83% Hispanic, and 4% White.

In 2017 Kimiko Unemoto Kishi, who had met future husband Fred in Minnesota near the end of the war, received an honorary Associate of Arts degree from the Los Angeles Community College Board of Trustees. As a student at L.A. City College in 1942, she was one of about 2,500 California Japanese Americans whose studies were halted by incarceration. Years before the southern California ceremony, Kimiko Kishi had established the Fred and Kimiko Kishi Endowment Fund at UC Berkeley to assure future instruction and research about the Japanese American experience and Asian diaspora at UC Berkeley, which three of their four of their daughters had attended. The fourth later worked many years at Cal.

Amache was declared a National Historic Site on February 15th this year, making it part of the National Parks Service. It’s the third one in Colorado, following Bent’s Old Fort and the Sand Creek Massacre sites receiving the designation.

The pandemic years of 2020-2023 saw a decline in public education outreach about the Japanese American legacy in Merced County and scuttled cherished community gatherings as well. But leaders of the Livingston-Merced chapter of the Japanese American Citizens League are planning an event for this May and hope to resume a Day of Remembrance event in Merced in early 2025.

AsAmNews is published by the non-profit, Asian American Media Inc.

We are supported through donations and such charitable organizations as the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. A big thank you to all our readers who supported our year-end giving campaign. You helped us not only reach our goal, you busted through it. Donations to Asian American Media Inc and AsAmNews are tax-deductible. It’s never too late to give.

Please also follow us on Instagram, TikTok, Facebook, YouTube and X.