By Raymond Douglas Chong

(This is part of our ongoing series, Lost Kinjo- a look at the more than 40 Japanese communities that disappeared after World War II. It is supported by funding from the California Public Library Civil Liberties Project and the Takahashi Family Foundation.)

Introduction

In the heart of the ‘Breadbasket of California,’ a small but vibrant community of Japanese Americans thrived in Bakersfield, a farming center nestled in the Tulare Basin of San Joaquin County, until June 1942. Despite the challenges, their farms, blessed with fertile soil and an arid climate near the Kern River, bloomed with various vegetables, nuts, and fruits, a testament to their resilience and determination.

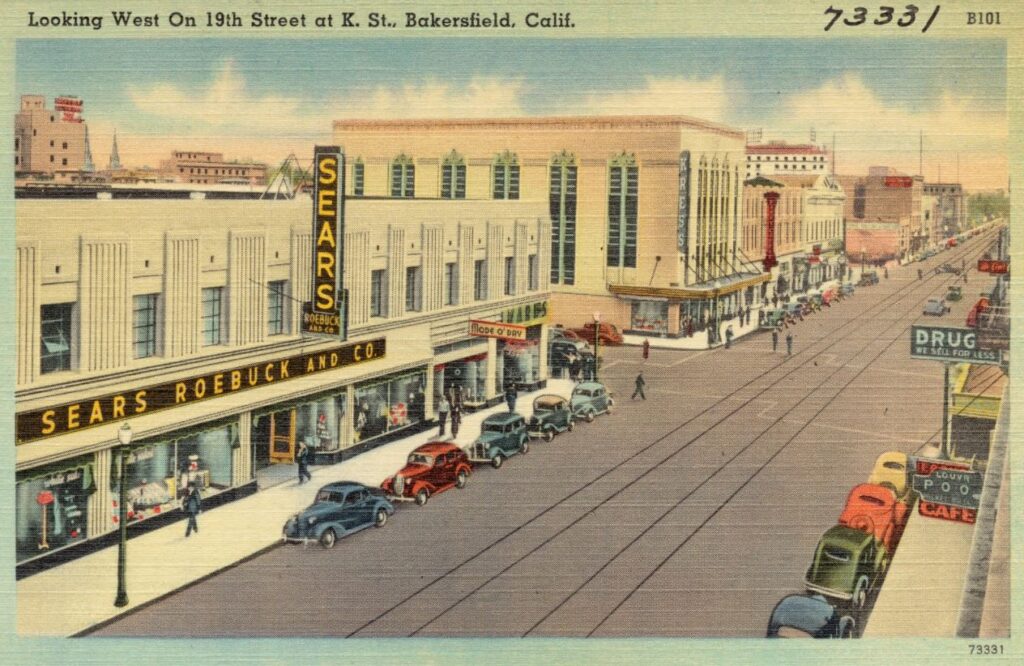

In 1940, 175 people lived in Bakersfield, and 61 lived in the countryside with seasonal laborers. Bakersfield Japantown had three hotels and seven stores, including a tofu-ya fish, and vegetable markets. Its society centered around the Japanese Buddhist temple and Japanese Methodist Church.

From the Manzanar National Historic Site Collection, on October 17, 2008, in Sacramento, Taeko Joanne Iritani recalled her childhood in Bakersfield with Kirk Peterson.

Kirk Peterson: Okay. So your father’s desire, you think, to get back into farming had to do with the family tradition?

Taeko Joanne Iritani: Well, being in Bakersfield, that’s when he saw most of the Issei were farmers. There were a few people who owned stores in Bakersfield, but mostly they had farms that they had to rent. And are you familiar with the alien land law? Well, I found out when my children were doing their biographies, autobiographies in, like, third, fourth grade, that we sat down and they interviewed Grandma, my mother. And that’s when I learned that not only could my father not purchase the land or lease the land, he had to rent. And I didn’t know that until I was a parent. So we have a lot of learning to do.

Peterson: So after your father got married in Tokyo, came back, and went back to Bakersfield, was he still working in the railroad at that time?

Iritani: No. He, that’s when he decided he would go into farming, but he had to learn about it first. And that’s why he lived like a bachelor and left his wife and child, maybe both boys already by then. But I remember my mother saying she was so lonely, she says, “What did I come over here for? To be left alone.”

Peterson: Back to the Japanese school that you went to, how did you feel about going, taking your Saturdays and going there? We’ve heard a lot of…

Iritani: Well, for us, as children, we had other friends who were our age, so that was fun. And out there in the country, you were isolated from other neighbors anyway. No one lived closer than a quarter mile from us.

Peterson: So it was a social gathering for you as a child?

Iritani: And also from there we were able to walk downtown to get new shoes. I remember my new shoes when I, my feet were growing so fast. And we could go to the library and get books.

Peterson: What town was the school?

Iritani: In Bakersfield. And just walked from the church where we had our Japanese school class, just on Saturday. People who lived downtown, especially the Buddhist children, had Japanese school every day, every day after school. Ours was very limited. But no, we also had a place to play across the street from the church. My father had bought that land using a Nisei man’s name, and he needed, he bought it so that we had a place to play. And later on, during the war while we were gone to Poston, then some of the Chinese people asked to purchase that land from him, and they did.

Peterson: Okay, let’s see. So about how large was the Japanese community in Bakersfield?

Iritani: Bakersfield didn’t have a large Japanese community. The stores that I remember, we had two… when evacuation time occurred, we had two fish markets, we had a couple of restaurants. There was one in particular called Asahi, A-S-A-H-I, where we usually, when my parents came into town to go to church, we also usually stopped in there, to the store, and picked up any Japanese foods. And we also picked up some tamales that she made. It was the most delicious… and she always had the non-spicy ones saved for us. They were beautiful, fat tamales, I’ll never forget hers. I’ve never seen any quite like it since.

Expulsion of the Japanese American Farmers in California

After the Congressional enactment of the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, the Japanese pioneers – Issei- arrived on the mainland to replace the Chinese farm laborers. They worked hard in the fields and orchards in the rich farmlands of California.

They successfully became farm owners and lessors in niche corps. Amidst the anti-Japanese sentiment of the late 19th century and early 20th century, White farmers felt threatened by their American success. Japanese American produced 9% of America’s truck crops. They dominated the labor-intensive fruit, vegetable, and floral markets. They also controlled the distribution of agricultural production in Los Angeles, Fresno, and Sacramento. In California, Oregon, and Washington, 63% of the Japanese American labor force engaged in farming, wholesaling, retailing, and transportation.

Under 1790 federal law, Congress denied the Issei American citizenship. On May 3, 1913, California enacted the Alien Land Law, barring Asian immigrants from owning land. That Law explicitly prohibited “aliens ineligible for citizenship” from owning agricultural land or possessing long-term leases over it but permitted leases lasting up to three years. Further amendments in 1920 and 1923, barring the leasing of land and land ownership by their American-born children’s parents or by corporations controlled by the Issei.

After the Pearl Harbor Attack on December 7, 1942, Austin Anson, the managing secretary of the Salinas Vegetable Grower-Shipper Association, urged Federal authorities to incarcerate all the Japanese people in the area. Anson stirred unjustified fears of sabotage. The White agricultural industry clearly aimed to crush the Japanese American farmers as competitors.

In Saturday Evening Post, May 1942, during an interview, Anson said:

“We’re charged with wanting to get rid of the Japs for selfish reasons. We might as well be honest. We do. It’s a question of whether the White man lives on the Pacific Coast or the Brown men. They came to this valley to work, and they stayed to take over. They offer higher land prices and higher rents than the White man can pay for land. They undersell the White man in the markets. They can do this because they raise their own labor. They work their women and children while the White farmer has to pay wages for his help. If all the Japs were removed tomorrow, we’d never miss them in two weeks, because the White farmers can take over and produce everything the Jap grows. And we don’t want them back when the war ends, either.”

After President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 on February 19, 1942, the War Relocation Authority implemented the evacuee Agricultural Property Protection Program. This program forced Japanese American farmers to relinquish farms (6,084 farms with a total acreage of 223,257 acres). White farmers appropriated the farms, whether owned or leased.

The words of Ron Inatomi, Founder, “Japanese Americans in the Produce & Floral Industry”

Cancer of Lust, Greed, and Quest of Power

The Grower-Shipper Vegetable Association is guilty as charged. Since the beginning of recorded history, every kingdom and nation of different ethnicities has contributed to mankind’s dark and shameful chapters.

The Japanese pioneer fathers and mothers farmed land that nobody would even consider, and they transformed the landscape. They worked their fingers to the bone for the sake of their children and descendants. WW2 came, and just a tiny fraction of the 1.2 million German Americans and 1.6 million Italian Americans were incarcerated. Yet over 120,000 Japanese, of whom 2/3 were natural-born citizens, were rounded up and forcibly removed into incarceration. Most were here for three to four decades, struggling to achieve their dream in the land of the free, and the vast majority lost everything they worked so hard for and were told they could only bring what they could carry into prison.

Like too many leaders in power throughout history, the pioneer fathers and mothers had nothing to do with Emperor Hirohito’s terrible ambitions. The only guilt the Isseis and Niseis were responsible for was working blood, sweat, and tears, and jealousy made them a target for the sins of the leaders in Japan for invading Korea and China.

The Niseis fought valiantly in the US Army, in both the European and Pacific theaters, to prove their loyalty and their families’ loyalty behind the barbwires. The 442nd Regimental Combat Team was the most decorated unit for its size and length of service in the entire history of the US military.

To remember is to honor the sacrifices of our pioneers.

Return To Bakersfield

After their return to Bakersfield from the Poston concentration camp, Japanese Americans faced anti-Japanese sentiment in 1945. White racists terrorized them with gunfire and house burnings across California. They faced hostile Whites with racial discrimination. A few tried to rebuild their businesses while in recovering their farmlands and properties. The families had difficulty finding housing. Bakersfield Japantown was already lost.

Taeko Joanne Iritani remembered her return to Bakersfield.

Peterson: So going back to Bakersfield, what kind of…

Iritani: No problem at all for us. My father had talked with Emma Buckmaster and visited with her. She’d have them, people stay in her house all the time. And he went there and made arrangements for us, and then made arrangements for when they were going to come out, he and my mother and my younger brother and my cousins. And that was a wonderful lady, wonderful committee that was so helpful, not just during the evacuation time, but followed through for when we needed them. And people were moving their things out of the church. So the churches, both Buddhist and our Methodist church, became hostels for people to stay in. That’s where my parents stayed for a while until they found a place to farm.

Peterson: How long did it take your parents to find a place to farm?

Iritani: How long…

Peterson: How long before your parents found a place to farm?

Iritani: I don’t know. I don’t think it was too long. You see, I mentioned all those stocks, well, my father still had some of that money, so we were fortunate. One of the things I learned from my brother in interviewing him was that I just assumed that he was getting the scholarship from American Friends Service Committee Nisei scholarship program that they had set up. And he said, “Oh, no, Pop paid for it,” for his college. So we were very fortunate that way. So it was not difficult at East Bakersfield High School. In fact, I repeated one of the classes and found out I had a good grade. [Laughs] I assumed I didn’t have such great teachers in camp, but we did all right. So I just went one year to high school, at East Bakersfield High School. My, after farming a while, my father found that he couldn’t continue, and he decided to start the nursery in Bakersfield. He walked around the area where he wanted to farm and start a nursery, and he got a petition to the neighbors to permit him to start in a residential area. So he knew enough to do that. And so my brother was out of the army after thirteen months, and that’s all he served because the war was over. And so he came home, and he and my father worked on the nursery.

Peterson: When did you, when did you… did you move back in with your parents?

Iritani: And then I moved in with my parents, and had my senior year at Bakersfield High School which was walking distance for me.

Peterson: So for your junior year then, who did you live with?

Iritani: I lived with a family that had been arranged by the committee.

Peterson: That was the popular girl in school?

Iritani: And I went to East Bakersfield High School and had the girls’ help. And the homes that they arranged for my sister and me were members of the Trinity church. So we helped with the dishwashing and babysitting for just that one year. So it worked out for me.

Peterson: And how did your father’s nursery work out for him?

Iritani: It was fine. There weren’t a lot of nurseries at that time, and he found out more about what kind of plants to put in and where to go to get it. And there were other nurserymen who helped him with that. And so my brother learned, and I understand from my brother Joe that he took some extension classes at UCLA to learn more about Japanese gardens and different things like that. And as I mentioned before, my mother learned all those names. Later on, years later, we took her on our trips, and she’d tell us what the name of that plant is and that plant is. [Laughs] I can’t do that.

Honorary High School Diplomas

In 2002, California Governor Gray Davis signed state legislation allowing incarceration victims to be granted their honorary high school diplomas. Ken Hooper, a Bakersfield High School teacher, organized a history class project to rectify this injustice.

Thirty-five students from old Kern County Union High School (Bakersfield High School), who were in the classes of 1942, 1943, 1944, and 1945, finally graduated. On June 5, 2023, Masako Inouye Fukuhara Masano Kizuka Holt, Tom Horiye, Akiko Tamura Mori, and Nancy Sakamoto Nakamura received honorary diplomas from Bakersfield High School. And relatives of the other 30 graduates received them too.

Monji Landscape Companies

Fred Monji, a Nisei (second generation), was born in Yolo, California, in 1919. His father was a farmer and Japanese restaurant owner. He graduated from Long Beach Polytechnic High School in 1938.

Fred Monji served with the United States Army in active and reserve duties from 1941 to 1951 during World War II and the Korean War. Deployed from Fort Snelling, he was the logistics officer for the weather station in Greenland during World War II. He worked at M and L Motor Supply in Saint Paul on auto parts.

In 1953, despite the risky discrimination environment, Fred Monji established Valley Landscaping Company in Bakersfield. His business thrived. After his 1987 death, his legacy Japanese American company is now known as Monji Landscape Companies. Daniel Monji, his second-generation son, and Aaron Gundry-Monji, third generation grandson, lead their team in landscaping design, outdoor living, and swimming pools & spas.

Close

Across the farmlands of California, the White agricultural industry effectively devastated the Japanese American farmers with the Alien Land Acts. In the aftermath of Pearl Harbor Attack, they crudely acquired their farms by relinquishment under the evacuee Agricultural Property Protection Program. As a sad consequence, Bakersfield Japantown, in the Breadbasket of California.

AsAmNews is published by the non-profit, Asian American Media Inc.

We’re now on BlueSky. You can now keep up with the latest AAPI news there and on Instagram, TikTok, Facebook, YouTube and X.

We are supported by generous donations from our readers and by such charitable foundations as the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

You can make your tax-deductible donations here via credit card, debit card, Apple Pay, Google Pay, PayPal and Venmo. Stock donations and donations via DAFs are also welcomed.