By Dianne Fukami

(This is part of our ongoing series, Lost Kinjo- a look at the more than 40 Japanese communities that disappeared after World War II. It is supported by funding from the California Public Library Civil Liberties Project and the Takahashi Family Foundation.)

More than 80 years after the start of World War II, there seems to be only three official reminders of the pre-war Japanese American presence in Berkeley, California: two plaques and an historic landmark status for an old laundry. Not much other tangible evidence exists of a population that numbered 1,300 in 1942 and operated 70 businesses, except in official records and documents. The rest is left to memory of a Japantown that was once vibrant and thriving.

According to the 1890 census, the first immigrants from Japan arrived in Berkeley in the 1880s. T. Robert Yamada, in his book published by The Berkeley Historical Society titled The Japanese American Experience The Berkeley Legacy 1895-1995, reports that those 19 pioneering Japanese didn’t stay long in Berkeley but another 17 Japanese arrived shortly after. Yamada writes that among those 17, the average age was 23 – a mix of students, domestics, and laborers. Like many immigrants from around the world, those 17 were sojourners, young men hoping to make their fortunes in America, then return home rich.

Some never did leave the U.S., among them a group of young Japanese men who in 1900 started a sake brewing company, an alternative to the high duty tax imposed on imported Japanese sake. Located on the corner of University and San Pablo Avenues, it seems likely it was the same enterprise described in an article by Richard Auffrey, who wrote of a sake company moving into the former Hofburg Brewery site. Because of financial and tax reasons, it closed after five years.

But other Japanese businesses began springing up in West Berkeley, many of them fueled by the refugees coming from San Francisco after the 1906 earthquake and fire. Like many other cities near San Francisco, Berkeley was attracting people who lost their homes and Japanese Americans were no exception. In 1905, the Japanese Association of Berkeley was founded, a chapter of a statewide alliance formed in 1900.

The discrimination against Japanese Americans began to grow. The 1907-1908 Gentlemen’s Agreement between U.S. and Japan halted the flow of immigrants to this country. T. Robert Yamada wrote of incidents in which a Japanese man was “roughed up” in front of his fraternity house, nursery windows broken by young people, and neighborhood protests whenever a Japanese business or renter tried to locate in the area. In its November 29, 1907 edition, the Berkeley Independent newspaper headlined: “Have J*ps Organized Army on This Coast? Indications are the 100,000 Brown Men are all Ready to Fight.” Not to be outdone, its rival, the Berkeley Reporter printed in December 1908: “Increase of J*ps Become Serious: Choice Section of the City Growing in Disfavor Because of the Little Brown Men.”

In 1913, California passed the Alien Land Law, which prohibited people not eligible for citizenship from owning property, which included Japanese immigrants. In 1919, Berkeley passed its first zoning law, creating districts in the city dictating who could live where and what type of businesses were permitted, a legal racist policy targeted at non-whites that resulted in segregated neighborhoods. Two Japanese and a Chinese laundry were kicked out of downtown because they were no longer legally allowed there, according to a 2019 article in the Berkeleyside by Jesse Barber. For the most part, Japanese were not permitted east of Grove Street (now Martin Luther King, Jr. Way) and restricted to the southern part of the city, certainly not allowed near the scenic hills area or the northern, lusher part of Berkeley. That year, the Real Estate Exchange of Berkeley took it a step further and unanimously supported a statement that opposed renting or selling houses and businesses to Japanese. Still, the Japanese endured. By 1910 there were 710 Japanese in Berkeley, many of them now families instead of the former bachelor society with the sojourner mentality.

Shut out from many other occupations, the floral industry was one arena in which the Japanese planted a foothold. One block of Berkeley in particular, bounded by Oregon, Russell, California, and Sacramento streets seemed to be especially popular. In a 2022 essay for the Berkeley Architectural and Heritage Association, Annie Ren wrote of that specific block and its significance. In 1909, a nurseryman named T. Kishibe rented a house and nursery operation at 1534 Oregon Street, moving away after a year. The next household at that location was Buicihi Mayama, his wife and daughter, and three fellow Japanese workmen. Mayama had immigrated in 1890 and had been a florist in Japan. With the nine greenhouses and two water towers, Ren reported that these nurseries were spread out over four lots on Oregon and Russell streets.

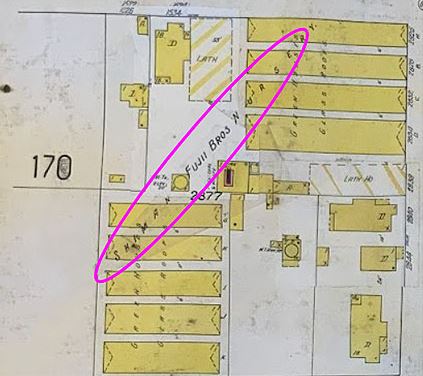

In the 1910s Mayama moved to Southern California, nevertheless, the idea of nurseries in that area had already taken root. The Yusas, Moritas, and Ikedas all moved onto that block and began their own forays into the floral or gardening business. However, Ren wrote that Mayama’s nursery business was transferred to Yamato Shemakawa, who immigrated in 1905, who then sold it to the Fujii brothers, Kakichi and Maruo, in 1924. Under the Fujii family, the nursery flourished dominating the block. Annie Ren provided a 1929 map and a modern day google overlay to show where the property lines were.

Courtesy: Annie Ren essay that appeared in 2022 edition of berkeleyheritage.com

Courtesy: California Flower Market collection, California Historical Society

Courtesy: Google map in Annie Ren essay of berkeleyheritage.com

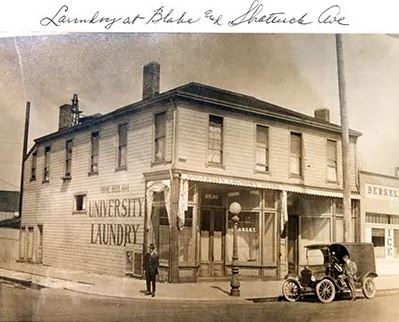

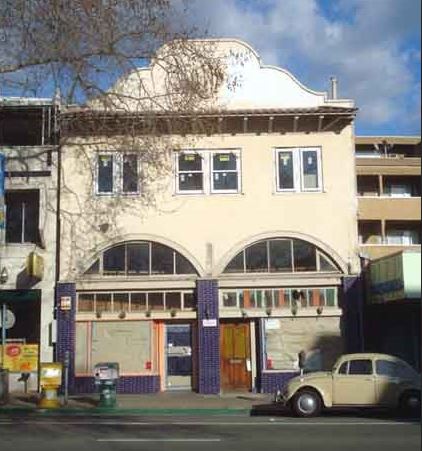

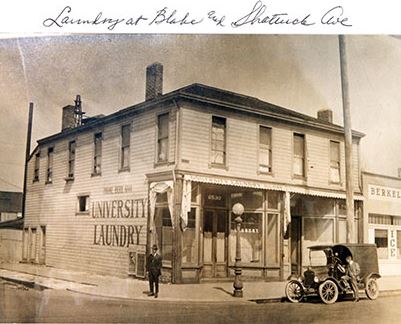

Restricted to this section of the city, the Japanese community began to thrive. Another popular enterprise was the laundry business. Pre-war Berkeley saw storefronts with names that included Sakura Cleaner, Hand Work Laundry, Ashby Laundry, Kyoto Cleaner, Nippon Laundry, and New Tokyo Cleaner. The biggest was the University Laundry at the corner of Shattuck and Blake Streets, founded in 1914 by five Japanese American families: the Fujiis, Kimbaras, Imamuras, Tsubamotos, and Tokunagas. According to a 2017 article in Berkeleyside, the families had all owned their individual laundries at some point, but decided to form a partnership. They lived together in separate bedrooms on the upper floor sharing a communal kitchen, dining room, and living room, while downstairs was the commercial laundry.

John Naoaki Fujii was one of the sons and in his 1986 memoir, remembered what it was like:

“Since the partners along with their wives and children all shared the upstairs living quarters together, the group developed a common communal life-style,” wrote Fuji. “All the adults worked long hours every day, usually six days a week. The women rotated kitchen and cooking duties periodically and child care was combined and shared…Among the men, each partner took responsibility for a part of the business. For example, Kurasaburo took care of the heavy washing and starching of clothes. The Imamuras did ironing and much of the mangle work. Mr. Kimbara went out to pick up and deliver laundry, In the first few years, pick up and deliveries were done using horse drawn wagons. Thus, two horses along with the wagons were maintained in the yard and barn at the rear of the building.”

As in many Japanese immigrant communities, the churches provided kinship and social bonding. In Berkeley, there were five major Japanese American churches also located in this small section of the city. The roots of the Berkeley Buddhist Temple began in 1911 when a group of 73 young men formed what was then known as the Berkeley Young Men’s Buddhist Association. For many years services were held at private homes, then moved to the Chitose Hotel on Channing and Ellsworth Streets until a building was purchased at 2121 Channing Way in 1921.

Courtesy: Berkeley Buddhist Temple

Courtesy: Berkeley Buddhist Temple

Right next door at 2119 Channing Way was what’s now known as the Berkeley Methodist United Church. It is actually a combination of two Berkeley Christian churches that served the Japanese American community: the Berkeley Japanese Methodist Church which was founded in 1892 and the Japanese Christian Church of the Disciples of Christ in 1903, becoming the Japanese Berkeley United Christian Church in 1929, and later housed at McGee and Carleton Streets.

Courtesy: Berkeley Methodist United Church website

Courtesy: Berkeley Methodist United Church website, Sue Yusa collection

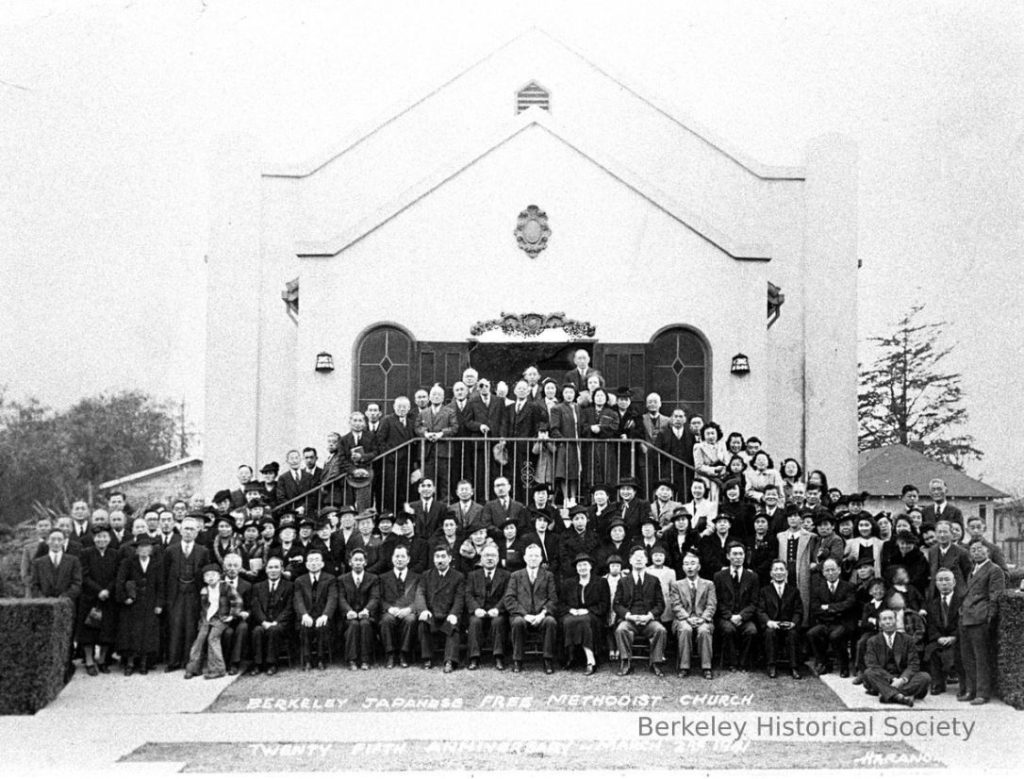

There was also the Free Methodist Church founded in 1916. From 1931, the congregation worshipped in a building on Derby Street, eventually moving to El Cerrito after the war.

congregation moved to El Cerrito in the late 1960s.

Courtesy: California Japantowns

Courtesy: The Japanese American Experience, The Berkeley Legacy 1895-1995, The Berkeley Historical Society

Believing that the teachings at other Christian churches were too liberal, a smaller congregation of Japanese Christians splintered off to form the Christian Layman Church in 1922.The initial seven families met and worshipped in the Sano home on Oregon Street and then the Yanagi home on Blake Street near McGee. By 1928 the congregation could no longer fit into a private home, and because church leaders were prohibited from buying property under the Alien Land Law, they bought a building on Ward Street under the names of four of their American-born children. The church website reports that by the late 1930s there were 25 families who were regularly attending Sunday service, with about 25 of them Issei (first generation Japanese) and 50-60 Nisei (2 nd generation Japanese American) in Sunday School.

Takahashis, Ryosaku Matsuoka, Genichi Hoshiga, and Kunisaburo Nomiya

Courtesy: Christian Layman Church Archives, Berkeley

Courtesy: Christian Layman Church Archives, Berkeley

The Berkeley Higashi Honganji Temple, founded in 1926, was started by nearly 60 immigrants. In 1936 they purchased two lots located next to the Fujii nursery property on Oregon Street and began building their own temple. Up until then, services and meetings had taken place at the Japanese Association Hall on Shattuck Avenue near Haste Street. So when construction was completed in 1938, there was a parade and much fanfare as the temple’s altar was moved to its new home.

Courtesy: Berkeley Higashi Honganji

Courtesy: Berkeley Higashi Honganji

Cultural institutions sprang up in the community. The aforementioned Japanese Association was the site for the Japanese Language School and cultural programs but the churches also spawned various other organizations as well. In addition to the religious community, another significant component contributing to the strength of Berkeley’s prewar Japantown was U.C. Berkeley. The state’s premiere public university of the era, Cal attracted Japanese Americans from all over, particularly throughout the state. Its popularity among the Japanese resulted in establishments such as the Japanese Men’s Club, which housed Japanese American male students on Euclid Avenue and around the corner from it, the Japanese Women’s Club on Hearst, and the Japanese Students Club, which was active by 1910. A number of organizations around campus also provided boarding arrangements such as the Berkeley Buddhist Church and a place on Shattuck Avenue called Berkeley Kaikwan Student Housing.

Courtesy: Berkeley Public Library

Courtesy: The Japanese American Experience, The Berkeley Legacy 1895-1995, The Berkeley Historical

Society

As further proof of the visibility of Japanese on campus, U.C. Berkeley had hired Chiura Obata as an art professor. Noted for his talent in merging Japanese art basics and perspectives with Western landscapes, Chiura’s classes and work were popular. Along with wife Haruko, who taught ikebana (flower arranging) classes, he opened a studio and art supply shop on Telegraph Avenue in Berkeley where he taught art classes and held exhibits.

Courtesy: Obata Family via Berkeleyside December 23, 2019

Courtesy: Donna Graves photo published in Berkeley Daily Planet 6/11/09

By the beginning of the 1940s, Japanese Americans in Berkeley had formed their own enclave in the southern part of the area where they were restricted. At the end of the 1930s, the Japanese American population number around 1,300 comprised of 330 families. Yamada reports in his book that there were 28 different organizations, churches, and private schools. As part of the Japantown Atlas project, cartographer Ben Pease created a map of Berkeley’s Japanese American community in 1940, indicating a thriving community with professional and retail services, a newspaper called the Japanese Women’s Herald, as well as the nurseries, florists, and laundries.

Life, as the Japanese Americans knew it, came to an end on December 7, 1941 when Japan bombed Pearl Harbor in Hawaii, although nearly everyone had felt the sting of institutional racism and discrimination even before that. In her book Desert Exile, author Yoshiko Uchida listed inquiries that had become commonplace in Japanese American households as she was growing up: “Do you cut Japanese hair?” “Can we come swim in the pool? We’re Japanese.” And finally, “Will you rent us a house? Will our neighbors object?”

But after Pearl Harbor, the change was dramatic. In an oral interview with the Urban School, Fumi Hayashi remembered what her sister experienced: “my sister had a friend who lived across the street from us. This friend told her, ‘I’m not going to play with you anymore because you’re part of the J*ps that bombed Pearl Harbor.’”

The FBI and government officials had been compiling lists of leaders among the Japanese American communities along the West Coast and they wasted no time in swooping in to arrest them, afraid of espionage. In her book “Desert Exile,” Yoshiko Uchida recounted how the FBI had picked up her father because he was an executive of a Japanese firm in San Francisco and along with dozens of other Japanese business leaders, as well as men who were active in local Japanese associations and those who taught in Japanese language schools. Uchida’s father was detained with about 100 other men at the Immigration Detention Quarters in San Francisco, then transferred to an army internment camp in Missoula, Montana.

Ted Nagata was a six-year-old boy in Berkeley at the time and remembered those days in a 2008 interview with Densho:

“Well, I know the FBI came and took our cameras and our binoculars and radios and things like that way before the notice went up on the telephone poles. But yeah, there was concern in our house, and I know my mother and father were having some serious discussions that I didn’t understand.”

Like Fumi Hayashi’s sister, Japanese Americans became blatant targets of racism. Uchida wrote of a being accosted at a Berkeley restaurant by an angry Filipino man. There were reports of shots fired at Professor Obata’s Telegraph Avenue store. In her 2008 interview with Densho, Helen Harano Christ still remembered the hurt she felt as a third-grader at Lincoln Elementary School in Berkeley.

“I was told that I couldn’t be first in line, even though I was standing in line almost all recess to be first in line, and I was, people, other kids, threw rocks at me on the way home from school. I was a target for rocks. I didn’t retaliate because I figured that they were always bigger than me, and usually boys, and so what could I do? And we went to Japanese school after school, and it wasn’t long before Obasan said, or Sensei said, that there would be no more school. And I heard conversations that she had burned all her books, that she wasn’t going to be found to be any kind of a subversive person.”

Later, Helen was informed by school officials that she would not be allowed to participate in the annual Maypole dance.

Kazuko Oyamada Iwahashi was 12-years-old and remembered that after Pearl Harbor she no

longer was invited to her classmates’ birthday parties. In her 2011 interview with Densho, she

also explained how the new government curfews and restrictions for Japanese Americans had a

very personal impact for her family, who owned University Avenue Nursery in between Grant

and Grove Streets in Berkeley:

“University was the dividing line on the south side of Berkeley and anything on the north side was restricted. Although people were living there, there were several families living all the way up University on the other side up to Vine Street and things because I used to go play with them… the Kamis were right across the street and the mother and father and the two youngest came and stayed with us at night.”

On February 19, 1942 came the announcement they had all feared: President Franklin D. Roosevelt had signed Executive Order 9066 that resulted in anyone of Japanese ancestry being forcibly removed from the West Coast. It wasn’t until April 21st that details became clear: the 1300 Japanese Americans living in Berkeley were informed they would be removed from the city by from April 28 th to May 1 st . They were given approximately one week to settle their affairs before they would be uprooted from their homes and businesses. The Uchida family, like others, no longer had their husband/father with them to help coordinate and take care of matters since he was being detained; Yoshiko’s older sister Kei had quit her job earlier to start preparing and the three of them while corresponding with Mr. Uchida for instructions, frantically worked to close up their household and find a new home for their beloved dog, Laddie.

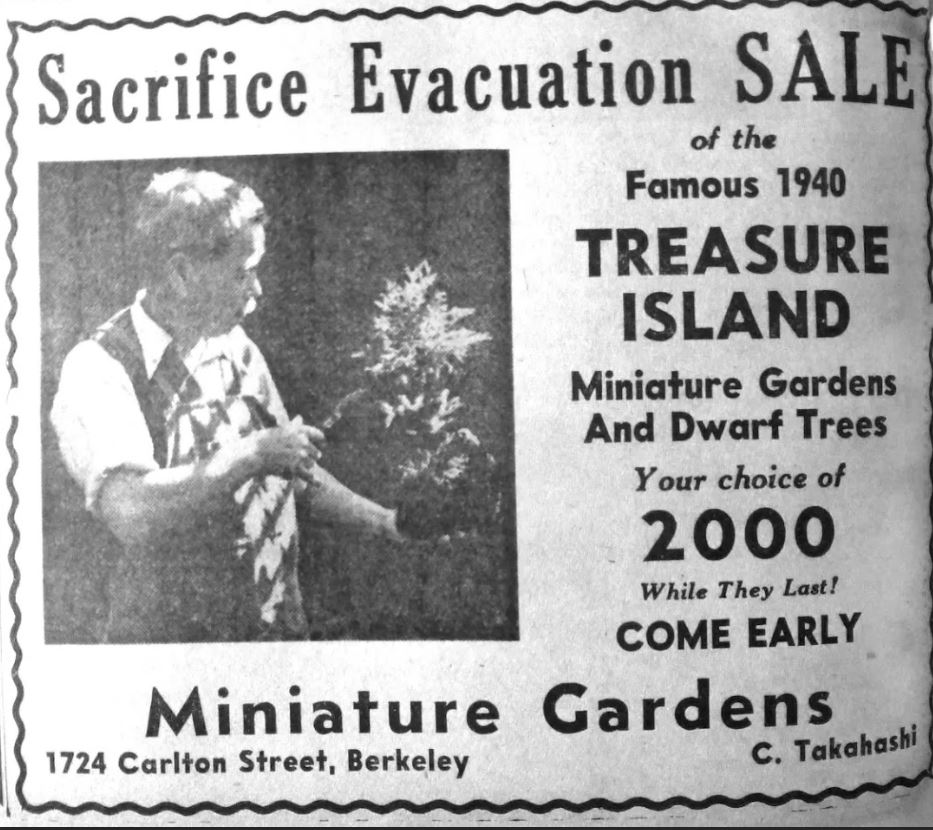

Other families had to deal with not just their households, but their businesses as well. Since the forced removal was scheduled just before Mother’s Day, all the nurseries and florists would never see the sales and profits they had worked so hard for. Kazuko Iwahashi remembered her father selling the inventory and his University Avenue Nursery, then bought an ad in the newspaper thanking his customers. The Fujii family, who owned the big nursery property on Oregon Street, advertised bargain rates in the Berkeley Gazette, while others such as the Takahashi family did the same.

In a 2019 interview with Densho, Yae Wada was grateful that her father’s laundry business, Ashby Laundry, was left in the hands of a Chinese neighbor family and that her father was able to take it back when he returned four years later. Chiyoko Yoshii Yano’s family also had a helping neighbor, as she revealed in a 2008 interview with Densho:

“There was a black family living next door,

and a black family living diagonally across the street from us,

and then there was an Irish family, but they were all

very sympathetic toward the fact that we had to do

what we had to do. And so they tried to help us, you know,

get ready to move. And my, the house that we

lived in, we were renting it from an Italian family,

and they felt sorry for us, too. They didn’t have to move,

but we had to move. And so they said that if,

if my father wanted to, he could buy the house.

It was a very nominal fee, you couldn’t buy a house like that anymore,

you can’t even buy a car at that price. But, so my

father agreed to buy it and leave everything there.

We didn’t have to store anything, we just left the

house, it was like going away temporarily.

And then my neighbor next door was a black man,

and he said, well, he could keep an eye on it.”

Because of their inability to own property, many people had nowhere to store their belongings and turned to the Japanese American churches, which offered to warehouse household goods in their boarded-up buildings until they were all allowed to return to Berkeley. Also standing by to help were non-Japanese churches, which in addition to storage space, offered assistance in finding new homes for pets and re-selling items.

For others, there were affairs of the heart to take care of before they left Berkeley to face an unknown future. In his article for Topaz Stories, Frank Kami wrote of his high school girlfriend Miyoko, whose family ended up going to Japan during the war as part of a diplomatic exchange and how they had promised each other that they would meet again. George Uchida and Michiko Fujii (one of the families from the University Laundry) fell in love at U.C. Berkeley and planned to marry after she graduated. But after they learned they would be sent to prison camps and possibly separated, they decided to marry at her parents’ home in Berkeley. Because their cameras had been confiscated, there was no hope of getting a wedding photo, until a White government photographer showed up and snapped some photos. It turned out their photographer was Dorothea Lange.

Courtesy: Frank Kami via Topaz Stories

they were ordered to the Tanforan Assembly Center. April 27, 1942

Courtesy: U.C. Berkeley, Bancroft Library

Unlike other California cities, there was a contingent of non-Japanese Americans in Berkeley who were opposed to the mass incarceration plan and said so publicly. According to T. Robert Yamada, then-Mayor Frank Gaines, former Mayor Claude B. Hutchison, and former Police Chief August Vollmer all went on record as wanting fair treatment for Japanese Americans. One group called itself the Fair Play Committee, organized to protest the incarceration and to mobilize public opinion. Members included: U.C. Economics Professor Paul Taylor; his wife photographer Dorothea Lange; Galen Fisher from the Pacific School of Religion; U.C. Provost Monroe Deutsch; former U.C. President David Barrows; Harry Kingman, who headed U.C. Berkeley’s YMCA Headquarters at Stiles Hall; Ruth Kingman, who was married to Harry, a leader at the First Congregational Church in Berkeley, and a fierce advocate for the Japanese Americans.

On the U.C. Berkeley campus, President Robert Gordon Sproul worked to try to keep Japanese American students on campus until the end of the academic year and wrote letters to other universities and colleges east of California requesting admission and financial aid for the students. Led by Harry Kingman, the campus YMCA and YWCA organized the Student Relocation Council to advise the students on how to continue their studies.

From April 28 to May 1, 1942 families reported to the First Congregational Church bringing only what they could carry, and were put aboard buses to transport them to the Tanforan Assembly Center in San Bruno, just south of San Francisco. Originally, the Japanese Americans were supposed to report to a vacant car dealership on Shattuck Avenue, but under the leadership of Ruth Kingman, the First Congregational Church requested that its site be the removal point so that it could provide hospitality and a warmer atmosphere. During the four days of forced eviction, Berkeley women representing the Congregational, the Methodist, the Baptist, the Friends, and the Presbyterian religious groups turned out to provide the departing Japanese Americans with coffee, tea, donuts, and sandwiches.

Courtesy: U.C. Berkeley, Bancroft Library

Courtesy: Oakland Museum of California. Gift of Chiura Obata

Third-grader Helen Harano Christ remembered the day she left Berkeley:

“When we were on the bus, nobody knew where we were going, as I recall. And the bus, the person who was the leader for the bus said, “Well, we don’t know where we’re going, but pull down the shades and we’re gonna go. And everybody be quiet, there’s to be no extra noises, and we’ll get through this.” And when we get there, then we could, we could be, visit in a, we could talk, talk out loud. So there was a lot of whispering going on on the bus. And my little brother was crying a little bit. He had the measles and he wasn’t very comfortable. So it was really, relatively a quiet bus ride from Berkeley. We went down Ashby Avenue and then across the bridge, Golden Gate Bridge, I remember all these places ’cause we had done all these things as, my parents had taken us to all these places. And we went through San Francisco and we ended up at Tanforan racetrack.”

At the time, no one could have foreseen that they would be gone for more than three years: the first stop at the Tanforan Assembly Center, which was formerly a racetrack and where many of them would be living in whitewashed horse stalls. The remainder of their incarceration for most, would be in the unforgiving Utah desert, at a newly constructed concentration camp 13 miles from the town of Delta, formally called the Central Utah Relocation Center, but would become better known as the Topaz Relocation Center, named after the nearby mountain.

After a time, many of the young adults and family men took advantage of the opportunity to leave camp early, as long as they did not return to the West Coast. College-age students wanted to continue their studies, young adults wanted to enter the workforce and get on with their lives, and husbands and fathers were eager to find jobs and housing in the outside world so they could send for their families. Also, as the years passed, knowing that Japanese Americans were not a threat to national security, the U.S. government encouraged them to leave the concentration camps to ease expenses. To that end, the pre-war governmental national propaganda against Japanese Americans did an about-face, converting to a campaign to reintegrate them into American society across the country as good, all-American, patriotic, contributing members of society. Photos below are examples of government photos released to the public with captions.

daughter, Suga Ann, are bid goodbye at the gate by a Caucasian staff member and her sister, Mrs. Suga

Baba. Mrs. Moriwaki has accepted a position in the home of Mrs. R. A. Isenberg (2175 Cowper Street),

Palo Alto. Her husband, Pfc. Yoshiaki Moriwaki, former Berkeley insurance broker, is fighting the Nazis.

Photographer: Mace, Charles E. Topaz, Utah.”

Courtesy: WRA Photo Collection, UC Berkeley, Bancroft Library

with their daughter, Pamela, age 2-1/2. Employed as a Junior Relocation Officer, Tats has been with the

Central Area staff of the WRA since January, 1944. They relocated from the Poston, Arizona, Relocation

Center, to which the Kushidas were evacuated from Los Angeles. May is formerly of Sacramento, while

Tats claims Berkeley, California, as his home town. Both are graduates of the University of California.

Pamela is one of over a dozen pre-school Sansei children in Kansas City. Photographer: Iwasaki, Hikaru

Kansas City, Missouri.

Courtesy: WRA Photo Collection, UC Berkeley, Bancroft Library

Tailor Shop as part-time and full-time workers. Reading from left to right are Edward Koyama from the

Rohwer Relocation Center, who is working part-time while attending the St. Louis School of Pharmacy;

Susie Tamaki, also a part-time worker, came to St. Louis from the Tule Lake Relocation Center and was a

former resident of Tacoma, Washington; Frank Hayashi who manages the tailor shop formerly resided in

Berkeley, California, and relocated from the Jerome Relocation Center approximately a year and a half

ago. In the foreground is Mr. Frank Wiltpert, a good humored tailor. Photographer: Iwasaki, Hikaru St.

Louis, Missouri.”

Courtesy: WRA Photo, UC Berkeley, Bancroft Library

Courtesy: WRA Photo Collection, UC Berkeley, Bancroft Library

Many of these families never returned to Berkeley, even when they were permitted to return to the West Coast. Helen Harano Christ’s father found work in Nebraska and the family stayed. Ted Nagata’s family remained in Utah. It wouldn’t be until 1945 that the first Japanese Americans would return to Berkeley.

Housing was the biggest problem when they returned home. Aside from the fact that most Japanese Americans had been renters before the war, the post-war housing shortage in the Bay Area combined with on-going prejudice posed a big challenge. Once again, the community churches played a big role, this time acting as hostels to provide shelter for the newly returning Japanese Americans. In a 1999 Densho interview, Ryo Imamura talked about his father, Kanmo Imamura, and part in helping others resettle:

“And then we returned to Berkeley, Calif.,

where my father was still the resident minister

there at the Buddhist temple.

I think he had started there right before the war,

around 1939. And like all the temples,

they were a kinda like repositories

for the belongings of people that were taken off to camp.

Of course this is where they came back to after the war

’cause they didn’t have homes any more.

So I think they did the same thing up in Berkeley

for people coming back, until they were resettled.

And so it’s a big part of my early life was living

with a lot of, lot of different Japanese Americans

who I didn’t really know, who just stayed

for varying lengths of time.”

Kazuko Iwahashi was 15 years old when she followed her father back to Berkeley, leaving her mother and younger siblings at Topaz until the camp was shut down:

“I stayed at the Berkeley Methodist Church because it was serving as a hostel until I could find a place to stay. Strange part of it is, it never occurred to me to ask my father where he was staying ’cause he didn’t stay at the church. So I have feeling he was renting a room someplace and doing his work, ’cause he was doing gardening… But my mother and brother and two sisters, because they had no place to go when the camp actually closed, went to Hunter’s Point in San Francisco where a lot of people went. And they stayed there a couple of months or I don’t know for how long, but then when my father found the house then they moved over.”

Those who owned property often came back unable to move into their homes with renters unwilling to leave or stored property gone or vandalized. Those who had thought their belongings had been safely stored in government warehouses were surprised as Ted Nagata revealed in his 2008 Densho interview:

The government said at the time that they would provide warehouses to store all this stuff, and, but there was one catch and that is you had to assume all the risk of storage, meaning that if they were stolen or damaged, the government cannot be held responsible. And so we put all of our things in the warehouses that the government provided, but after the war, we were notified that we could not come back to pick ’em up, because they were all gone, and where they went, I have no idea. But I think that happened to most of the people that put them in there.

Nagata’s family was one of many that never returned to live in Berkeley after the war. While incarcerated at Topaz, his mother suffered mental health issues and was not able to join the family went they left.

“And even after the war, when we came to Salt Lake,

we were, my sister and I were put into an orphanage

because my father couldn’t quite handle us

and finding a job and trying to find a place to live.

So we spent a year in St. Anne’s orphanage,

which by the way is still here,

and it’s quite a large Catholic church.”

Members of the Christian Layman Church found that their church had been rented out to the War Relocation Authority for public housing while they were gone and their stored belongings put into a WRA warehouse. When they arrived back in Berkeley in 1945, the tenants at the church refused to leave and were evicted in 1946, opening the way for church members to live there until they could find permanent housing. It’s not clear whether those stored possessions at the WRA warehouse was related to Nagata’s experience of never finding his belongings.

During their time away, the Japanese Americans discovered that Berkeley had changed. The storefronts they used to rent were replaced by new retail shops; most of the first-generation Issei no longer had the energy or finances to begin their businesses again. Many of the buildings the Japanese had occupied, both residential and businesses, still existed but had changed hands. As families struggled to get back on their feet, they moved farther away from what had been the unofficial anchor area for the pre-war Japanese community in south Berkeley. The foundations of what remained were essentially the Japanese American churches. Currently three still remain where they were built before the war: Berkeley Buddhist Temple on Channing Way, Higashi Honganji Temple on Oregon Street, and Berkeley Methodist United Church on Carleton Street.

In 2007/2008 the historical project Preserving California’s Japantowns researched and documented the remnants of the state’s pre-war Japanese American presence in nearly 50 locations, including Berkeley. Project leaders Donna Graves and Jill Shiraki worked with cartographer Ben Pease, who based on their information, was able to create the 1940 Berkeley map that was mentioned previously. At that time, a good number of pre-war businesses were still existing, albeit not necessarily being operated by Japanese Americans. But much has happened in the past 17 years, and many of those buildings that were still standing in 2007 are also now gone.

What has changed though is a newfound respect for the history of Japanese Americans in Berkeley and their contributions. In 2008, the City of Berkeley recognized Pilgrim Hall at the First Congregational Church with a plaque acknowledging that it was the assembly point for Japanese Americans in 1942 when they were forcibly removed. Professor Chiura Obata’s contribution as a Berkeley resident was honored in 2009 when the Berkley Landmarks Preservation Commission designated his art studio and shop at 2525 Telegraph Avenue as an historic and cultural landmark. Then in 2016, the City of Berkeley honored him with a mural painted across the street from his studio and a plaque.

On the 75 th anniversary of the forced removal from Berkeley, in 2017, recognition was bestowed upon an unexpected building. The University Laundry, located on Blake and Sutter, which had been run by five immigrant families that included the Fujiis, was designated landmark status by the Berkeley Landmarks Preservation Commission. In his application, historian Steve Finacom wrote: “The story of the Fujiis and the other Japanese-American families in establishing lives, homes, and businesses in Berkeley mirrored the experience of many other Japanese-Americans,” Finacom wrote in the application. “The University Laundry building is a tangible and physical reminder of this story and part of Berkeley history, as well as the broader history of discrimination against, and accomplishments of, Japanese-Americans.”

Courtesy: Dianne Fukami

Courtesy: Donna Graves

American families in the early part of the

Courtesy: Dianne Fukami

Today many of the physical linkages to a Berkeley Japanese American community are gone. The nurseries, cleaner and laundries, stores, and florists are memories. But what remains is the will to remember: in October 2024, the Berkeley Historical Society and Museum will be debuting a Japanese American exhibit to jog the memories of those still present and to educate those who will pass on the history for future generations.

AsAmNews is published by the non-profit, Asian American Media Inc.

We are supported through donations and such charitable organizations as the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Donations to Asian American Media Inc and AsAmNews are tax-deductible. It’s never too late to give.

Please also follow us on Instagram, TikTok, Facebook, YouTube and X.