By Raymond Douglas Chong

(This is part of our ongoing series, Lost Kinjo- a look at the more than 40 Japanese communities that disappeared after World War II. It is supported by funding from the California Public Library Civil Liberties Project and the Takahashi Family Foundation.)

Until 1942, Lompoc Japantown, the “Flower Seed Capital of the World” in Santa Ynez River Valley,” thrived on California‘s Gold Coast. According to the 1940 federal census, 190 Japanese Americans lived in Lompoc.

Background

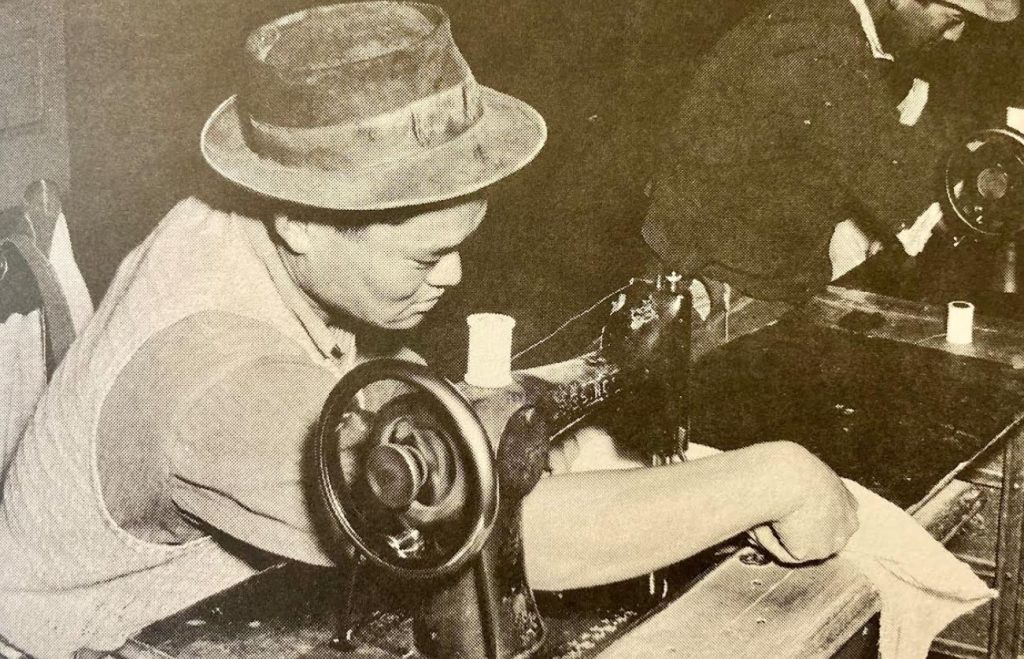

Lompoc Japantown emerged as a farming center for the Nikkei community. In 1940, 20 businesses flourished along Ocean Avenue, including Hinode Store, H.S. Iwamato General Merchandise, and New China Café (Chop Suey).

Harry Iwamato, owner of H.S. Iwamato General Merchandise, was hugely successful when he grandly opened the West Side Food Center in October 1941. Nobuijiro Inouye owned the busy Hinode Store. Genzo Murakami served Chop Suey dishes at his New China Café.

Burpee Seed Company cultivated flower seeds at its Floradale Farms. Setsuo Aratani’s Guadalupe Produce Company owned 100 acres of farmland with a packing shed. Chitose Kitaguchi farmed his asparagus field.

In his dissertation, Dr. Kent Edward Haldan wrote, Our Japanese Citizens: A Study of Race, Class, and Ethnicity in Three Japanese American Communities in Santa Barbara County, 1900-1960 (2000). He recognized Lompoc Japantown as “a more egalitarian community than that of Guadalupe.” In 1940, most household heads were farmers, shopkeepers, farm managers, and laborers.

Incarceration

The War Relocation Authority incarcerated Lompoc Japanese Americans in the Manzanar concentration camp in the high desert of Owens Valley in California and the Gila River concentration camp on an Indian reservation in Arizona.

Dr. Harlan mentioned the desire of White farmers to remove Japanese American farmers from the Lompoc Valley and Santa Maria Valley in the aftermath of the Pearl Harbor Attack. The Western Growers Protective Association bitterly complained that Japanese farmers owned the best farmlands. They wrote, “American farmers have not been able to compete with them due to their low standard of living.”

Tony Armas, mechanic for Jintaro Fukawa, was interviewed about the evacuation situation in Lompoc as part of the Lompoc Oral History Project by the Lompoc Museum and Lompoc Valley Historical Society.

Tony Armas: They’d just go up to the house and knock on the door and ask for so and so and they knew where all of them were. They had a record, I guess, of all of them. And they went to the house where my boss lived and he was in the shop where I was working on a tractor. And so she told them what it was. They came over there and took out their billfold and a badge of some kind and said they were the authorities. And I happened to look over and I could see some other Japanese that I knew. They came in caravans – they wanted them all at once. And they took every Japanese alien, men, from this valley, I believe, in the first day.

Interviewer: What did they do with the families then?

Armas: Families just stayed and tried to find out what’s gonna happen next. And they just brutally took their people away from their families. That’s the way I could put it.

Interviewer: They didn’t give them time to pack?

Armas: They didn’t give them time, no more. My boss asked if he could get an overcoat in the house, and one of the officers went with him. They came back out and started to get in this truck, an army truck – it was green on the side. You could see it was a military truck. Then there was also a bus. I think the bus was mostly government people in case there was trouble or anything. Then no more than when he got ready to step up on the truck, (the tailgate was down), he took out his billfold and his wife started to cry and he gave his billfold to his wife.

Interviewer: They didn’t get to take anything?

Armas: They didn’t get to take nothing. They did allow them to go in and get an overcoat.

Interviewer: Were these families compensated in any way?

Armas: They didn’t give them nothing. They lost everything they had.

Interviewer: And then the families had to leave?

Armas: Later the families had to leave. I wasn’t there when they took the families. It was about a month or two later, the families went to join them wherever they was at. I heard they had taken some down to Santa Anita Racetrack. They took the horses out and made housing for them to live in there. They took them to different parts of California. Some of them they took clear back into Colorado.

Interviewer: Did the government actually sell their land to other…?

Armas: They didn’t own their land. There were only two Japanese families that owned land in Lompoc and that was the Inouyes and the Kitaguchis out here by Rivaldis. They were the only two that I know that owned land because they were American citizens. They couldn’t even have the lease in their name. They had an American citizen that used to sign all the leases in Lompoc for all the Japanese.

Interviewer: This was before the war broke out?

Armas: Before the war broke out. He would sign all the leases. George Nishimura, he was about 35 or 40 years old – he was an American citizen. He was the one that had a packing shed here, and he signed all the leases for all the Japanese. And these two people that owned the land – they couldn’t take it away from them. People just started farming it because it was vacant. But they came back. These two families came back. The rest of them tried to come back and start businesses here and the attitude of everybody – all the farmers in the valley – banded together and they would just not lease a piece of ground to a Japanese. Now Guadalupe was a little bit different. They did come back there and started farming there.

Interviewer: The ones that left here then, more or less, just had leases?

Armas: Just had leases.

Interviewer: The two that came back then, were they able to regain their property?

Armas: They were able to start farming their property. One of them I knew real well. I was farming their ground because I went to school with one of the daughters.

Interviewer: Which one was this?

Armas: Inouye, Toshi Inouye’s folks owned the land right back over here. There was fifteen acres in one spot and about ten acres in another spot. And I, on the side, was doing some farming. So I farmed that ground for them toward the end of the war. I mean, at first I don’t know who had it. Some person let it grow into weeds and nobody had it and then somebody went in there and worked it up and planted it. They lost all their equipment. Most of these farmers had tractors, big tractors, Farmall tractors, planters, rollers, everything it would take to farm vegetables. They just left it sit and most of them were paying on that so much each year. A lot of it got repossessed by the companies they had contracts with and some of it was sold for whatever they could get. Who was in charge of that I don’t know but I heard that Grossman was in charge of quite a bit of selling some of the equipment. They got little or nothing for it.

Interviewer: Your boss’ name was……..

Armas: He was George Fukawa.

Resettlement

When the Japanese resettled in Lompoc Japantown after their incarceration in 1945, they found housing and employment challenges. They had no place to stay as their properties had all been sold or confiscated. Whites had burglarized or vandalized their properties during their incarceration. They vandalized the Japanese Language school. They abandoned the New China Cafe. The White farm employers boycotted their employment. The White residents were antagonistic against them. The White racists blatantly terrorized them to leave again.

John V. McReynolds authored a subliminal book, Vanished: Lompoc’s Japanese, The story of Japanese Americans who lived in Lompoc before World War II. It’s about the successful efforts of local and state officials in pushing for the evacuation of Japanese Americans from the Pacific Coast. One of the greatest tragedies of this forced removal.

T.M. Tom Parks, Parks Packing owner, Sydney Andrson, Santa Barbara County Farm Bureau advisor, and Ralph Kelly, Santa Barbara County Deputy Sheriff, led the terrorist campaign against the resettled Japanese Americans.

During the reign of terror in Lompoc, the Nikkei community faced:

- Threats sent to them in anonymous letters

- Fires that mysteriously broke out

- Clauses in farm leases that excluded Japanese Americans

- Retailers that refuse to do business with them

- Discrimination in hiring

- Harassment of children

- Signs at gas stations that bluntly stated “No J*ps and Germans Allowed” at gas station

Armas recalled when an oil company refused to sell diesel fuel for farming to Victor Inouye.

Interviewer: The two who came back, was there strong feelings against them by the farmers in the valley?

Armas: Yes, I heard it from the horse’s mouth that an oil company that was supplying diesel fuel refused to deliver diesel fuel to this one Japanese that wanted to start farming. He just flat refused to deliver fuel to him. This was Inouye, and they wrote to the oil company that they had credit with, Union Oil Company, that they refused to deliver diesel fuel to them. They were all banded together in Lompoc. They wasn’t gonna let Japanese back into Lompoc and they did a good job of doing that, because you don’t see any of them farming in Lompoc. I mean, I think there is one or two that were born here. They’re farming here. The company wrote to this oil company man and told him “You will deliver fuel to Inouye.” He made the brag that he wasn’t going to deliver any fuel to them, and later I heard the company gave him strict orders that he’d lose his dealership if he would not deliver fuel to them.

Interviewer: This was a representative here in Lompoc?

Armas: Yes, the delivery man. Delivered here for years. There’s a few of the die-hard farmers, the bigger farmers here in the valley, that just didn’t want to see them come back. You see, they had gotten so poor while they were farming here. They figured they could do it good. We didn’t need the Japanese anymore. But the Japanese came in here and showed them what they could do with these parts.

Interviewer: Anything else about the Japanese that you remember?

Armas: Well, all I could say I enjoyed working for near five years for the one that I worked for. That’s the first job I had. After my dad passed away, he leased thirty-five acres. He didn’t even get a crop out of it. The river took it. He gave me a job knowing that I was alone. He helped me out with his equipment to do the farming. The rest of the farming that my dad used to do was with horses. My boss had these two big tractors and he says, “You getting ready to farm your ground? Here, take my equipment.” Never charged me a penny. Even furnished the fuel.

Eric Thomsen, District Relocation Officer for the War Relocation Authority, assisted the Japanese Americans to resettle in Guadalupe from 1945 to 1946.

In his final report, Thomsen noted the poor treatment they received from the Santa Barbara County Sheriff. “We have only high praise for the Sheriff’s office in Santa Barbara County with the exception of the deputy in Lompoc, Kelley, who has often made it his business to obstruct relocation in ways which made it difficult to pin anything on him.”

Thomsen recognized the White opposition against their resettlement. “The Farm Bureau and their camp followers, some of them in the Extension Service, and some in the American Legion… resisted relocation wherever they could, especially in Lompoc, Guadalupe, and Santa Maria where they were determined insofar as they could prevent it, we should never get a single person back.”

Thomsen chatted with Sydney Anderson, Santa Barbara County Farm Bureau advisor. “The most intense, and in the long run the most serious opposition, came from the Farm Bureau crowd and by implication, the Agricultural Extension Service. I had been in town a month but Sydney Anderson, the Farm Advisor for Santa Barbara County, hopped all over me for “trying to find leaseholds for our enemies.” When I challenged him on “our enemies,” he said he meant anyone of Japanese ancestry and protested that every bit of available would be needed for “our boys” when they returned from the war. He called it “mere quibbling” when I replied that I too was looking for land for “our boys” since naturally under the Alien Land Act it had to be the native-born Americans, the Nisei, the very boys who were up to their necks in gallant battle for their country and ours, yes, also against Japan.”

Thomsen reported that the Lompoc Agricultural Employers Council boycotted the employment of the resettled Japanese Americans. “In Lompoc, as late as November, an area of agricultural employers voted against only two dissenting votes to hold the lines and refuse all employment to the Japanese.”

By 1948, only two families remained. The Kitaguchis farmed their asparagus fields. The Inouyes farmed and operated their Hinode Market, selling groceries, fresh meat, fish, wine, beer, notions, and housewares The terror campaign ultimately destroyed the resettled Nikkei community. By 1950, only one business, Hinode Market, remained, and only three people, the Inouyes, lived in Lompoc. Before in 1940, 20 businesses and 190 people. Victor and Toshi Inouye retired in June 1968 when they closed Hinode Market.

Close

In 1942, Lompoc Japantown, a thriving Nikkei community, vanished forever. The terror campaign by the White farm industry successfully crushed the resettlement of the Nikkei community. No remnants of the Lompoc Japantown exist now except for memories and archives.

A stony monument in Lompoc silently reads:

IN MEMORY OF THE JAPANESE PIONEERS OF LOMPOC VALLEY

AsAmNews is published by the non-profit, Asian American Media Inc.

We are currently funded by our readers and such charitable foundations as the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, AARP, Report for America/GroundTruth Project & Koo and Patricia Yuen of the Yuen Foundation.’

Find additional content on Bluesky, Facebook, Instagram , Tiktok, X, and YouTube. Please consider interning, joining our staff, or submitting a story, or making a tax-deductible donation.

You can make your tax-deductible donations here via credit card, debit card, Apple Pay, Google Pay, PayPal and Venmo. Stock donations and donations via DAFs are also welcomed. Contact us at info @ asamnews dot com for more info.