By David Hosley

(This is part of our ongoing series, Lost Kinjo- a look at the more than 40 Japanese communities that disappeared after World War II. It is supported by funding from the California Public Library Civil Liberties Project and the Takahashi Family Foundation.)

When Shohei Ohtani decided he wanted to play professional baseball in America, it was not a coincidence, aside from lots of money, that he signed with the Los Angeles Angels of Anaheim. Not far from Angels Stadium is the Gardena Valley, home to two cities with the greatest percentage of residents of Japanese ancestry on the U.S. mainland. Now that he’s a Dodger, Gardena and Torrance are even closer.

Torrance is first in Japanese and Japanese American density and its neighbor Gardena is second. You can bet “Shotime” has lots of fans in both places, which trace their history back to the time the valley was a hotbed of berries and other fruits and vegetables that fed Southern California during boom times before and after World War I.

Gardena had the first Japantown in the valley, and today there are still many stores, restaurants, community groups, places of worship and even a language school to serve Japanese Americans and Japanese nationals who make their homes in the area. In the past few decades, a number of Japanese corporations have located facilities in the Gardena Valley.

The Japanese culture is reflected in Gardena through dozens of businesses, often in clusters and sometimes in entire malls. In two blocks of South Western Avenue, there are three gems featuring fresh tofu, mochi sweets and traditional meals and beverages.

The residents of Japanese heritage join other Asian Americans to make up about a quarter of Gardena’s population. African Americans are about 20%, while Hispanics are about 40%, Whites 8% and 1% Native American. It is a remarkably diverse city, with a history of settlement that goes back at least 10,000 years.

Meiji Tofu specializes in fresh soy milk and tofu. Its zaru-style or traditional Japanese tofu is made with a woven bamboo strainer as opposed to a mold and has many fans, both vegan and non. Customers are known to drive from all over Southern California for the high quality of its products.

Just down the street, Chikara Mochi’s artisans are hand making pristine treats whose beauty is matched by their flavor. The storefront is nondescript but it’s hospital spotless inside with rows of intricately designed mochi and manju in display cases. While the number of Japanese confectionaries is sadly shrinking in America, Chikara is well supported by the locals who are willing to observe the family store’s policy of payment in cash only.

Across Western Avenue from the sweet shop is Azuma Japanese Restaurant, featuring Izakaya style lunches and dinners. Chicken katsu with curry sauce, teriyaki beef, and tempura are mainstays. That’s comfort food for Japanese Americans who have been coming to Azuma for decades.

The depth of the current Japanese American community can be experienced in the Pacific Square Shopping Center on West Redondo Beach Boulevard. It’s anchored by the Tokyo Central and Main store, which includes a food court. Owned by the Marukai Corporation, it features Japanese products that range from basics like ramen and sushi to clothes and appliances. The company has had a presence in the region since the 1960’s, and calls itself the largest Japanese market in California, with a dozen locations.

Surrounding the mall’s anchor are Asian businesses, including a bakery, dim sum house, several wonderful noodle places, and Meiji Pharmacy, which has been operated by members of the Yamashita family since 1977. There’s even a hotel at one end of the mall, complete with its own Japanese restaurant.

Not far away is a unique setting for eating out—the Gardena Bowl Coffee Shop, which is at once a time warp and the latest in fusion cuisine. It offers Japanese, Hawaii and American cuisines, sometimes combined in the same dish. How about fried rice spam? Or Kalua pork and loco moco? Eat the old-fashioned way at the counter or relax at tables, at times filled with three generations of Japanese Americans who can trace their family roots in the Gardena Valley back a century or more.

Native American and Californio Beginnings

The initial human occupants of the valley were the Tongva, who lived throughout what is now called the Los Angeles Basin, and the nearby Channel Islands. Initial contact with European explorers included Spanish sailors in the 1500’s and an overland expedition via Mexico in the 1700’s, which resulted in a series of missions and the decimation and enslavement of the Tongva, whom the Spanish called Gabrielinos after one of the missions. Mexico took the missions from the Spanish in 1821, and U.S. citizens and others soon arrived in increasing numbers. The Spanish had established an agricultural economy and gave out land grants, including one of 43,000 acres encompassing today’s Gardena Valley, which is 10 miles southeast of Los Angeles International Airport and six miles inland from the Pacific Ocean.

That Spanish rancho was broken up over the years into smaller parcels, and settlers came west after the Civil War until the remaining Native Americans and Mexicans became the minority. Speculators divided one agricultural area into lots, and thus a new town grew in the Gardena Valley. A rail line, the Los Angeles and Redondo Railway, further created commercial connection of the rural agricultural area to population centers in southern California by the 1890’s.

The Making of Berryland

Strawberries, blackberries, and raspberries grew particularly well in the Gardena area because of the soil being watered by the Dominguez Slough. The Strawberry Park neighborhood got its name from its primary crop, and farm workers were needed to plant, prune and harvest the nearly year-round production. Starting in the 1890’s, many of the laborers were Japanese immigrants.

Single men from southern Japan who sought higher wages travelled the Pacific Ocean to west coast ports and were paid about a dollar a day in California. Joe Kobata left Wakayama in 1890 and took a ship from Kobe to Seattle, with his final intended destination stated on a manifest as Los Angeles. By 1905 he was living in Gardena, had a family and was growing flowers. Three generations would live there, wholesaling flowers through the L.A. Flower Mart, where a relative had a business.

After years of working, some of the immigrants saved enough money to enter arranged marriages. By 1910, Los Angeles had the highest percentage of Japanese in the country, its ranks bolstered by several thousand Nisei who fled San Francisco after the 1906 earthquake. Many chose to stay downtown in Little Tokyo or Boyle Heights, but others lived near the berry fields of Gardena Valley.

Asahiko Sawada was not a typical immigrant laborer. He arrived in 1901 at 26, leaving his wife back home on Kyushu Island. His plan was to get work and send a portion of his pay to his spouse. According to a magazine article, Sawada didn’t keep up with the support, and learned he was divorced in 1909. But then, Sawada had moved around the west, working on railroads and in agriculture. In 1918, now in his 40’s, Sawada started looking for an arranged marriage, requesting someone closer to his age.

He was put in touch with Urako Sakata, a woman in her mid-30’s from Kunamoto in southern Japan. She had been an unwed mother as a teenager, shaming her wealthy parents who dealt in the rice trade. After her son died in infancy, she was eager to start a new life. Urako and Asahiko met for the first time when her ship arrived in San Francisco in early 1920, and they wound up in Southern California where he worked in the fields and they settled in Gardena.

Building A Community

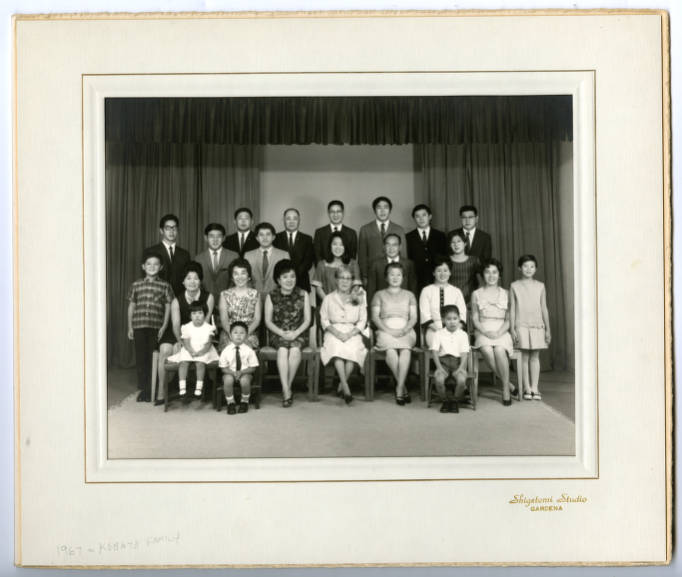

Immigrant couples usually started families, as the Sawada’s did, and those working in the valley helped Gardena grow by forming churches, community associations, and sports teams. Their children attended public schools; their regular school days augmented by Japanese classes paid for by their parents. Founded in 1912, Moneta Gakkuen was more than just a language school. It also transmitted the culture of Japan to young people, which was very important to their immigrant mothers and fathers. The school’s leadership changed its name in the 1960’s to the Gardena Valley Japanese Cultural Institute as its programs grew, playing a vital role in community building over the decades.

The mix of crops changed in the valley between the world wars, with berries losing out to ones that would bring a better return, and some farmland was soon devoted to new houses. In 1930 Gardena was incorporated as a city, including the rural communities of Moneta and Strawberry Park, with a total population of about 20,000. Although tiny in comparison to Los Angeles, its percentage of Japanese and Japanese Americans was significant. By then, the Sawada family had moved south to Huntington Beach. The 1930 U.S. Census shows them living among Japanese neighbors who worked on berry farms and a poultry operation. By that point Asahiko was a middleman wholesaling fruit.

Anti-Japanese Laws

There were consistent efforts in California’s legislature, and nationally, to limit immigration from Japan in the early 1900’s. Elected officials also acted to deny a path to citizenship for the first generation. Alien Land laws restricted acquiring property.

Home ownership in Los Angeles, for instance, was much less than other ethnic groups, or the population on the whole. Some Japanese immigrants got around the laws by putting homes and farms in the names of their children, who were citizens by birth, or by having friends hold title for them. The Kobata farms were in the name of a relative who had been born in the U.S. in 1902.

Harold Kobata, Harry and Umeno’s son, was born in Gardena in 1926, and talked about his growing up in an oral history interview. He recalled going to Amestoy Elementary School and then taking Japanese classes on Saturdays for a half dozen years at the Moneta Gakkuen. In junior high, he went every weekday after regular school was over since the language classes were held very near the campus. His Saturdays were often devoted to playing sports at the YMCA, and the whole family would go to Wakayama Kenjinkai picnics on weekends. The Japanese business hub in Gardena, according to Harold Kobata, was concentrated along Redondo Beach Blvd. and Western Avenue.

The Shock of Pearl Harbor

Everything changed with the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, although it wasn’t immediately evident to Kobata. “Then the next day we went to school as usual, and you know there was some commotion, but there wasn’t that much. I mean, people in Gardena they knew the Japanese quite well.”

Kobata says he didn’t become anxious until a few weeks later, in January, 1942. “We didn’t know what was going to happen and just anticipate what’s ahead for us.” Part of the Kobata family, including Harold, moved inland to Salt Lake City. That put them outside the zones that had been established in California, where restrictions in travel and curfews were in place for Japanese and Japanese Americans. “My older brother and Uncle Jimmy had to stay behind and sell off the Easter lily crop, because that was the main money crops.”

Because they stayed in Gardena Valley, both men were subject to the subsequent Executive Order 9066, which gave the government the power to assemble residents of Japanese ancestry. The pair were incarcerated at Santa Anita Assembly Center, held under guard while more permanent facilities were hastily constructed in the interior of the country. The Kobata’s had arranged for a minister to watch out for their holdings and live in their house. The foreman, a Mexican immigrant, managed the farming side of their floral business.

For Harold Kobata, his parents and other siblings, their new life in Salt Lake City was in great contrast to the fate of the more than 110,000 Japanese and Japanese Americans living in concentration camps starting in the late summer of 1942. Harold completed high school, working after school and on Saturdays as a gardener. Older family members had started a gardening business in Salt Lake City and everyone was expected to help out.

As the war wore down, Jimmy Kobata returned home first to Gardena Valley to get housing sorted out while Harold finished up his senior year in the spring of 1945. Diploma in hand, Harold, several siblings and a sister-in-law had driven back to southern California in the family car.

Harold went on to take classes at Compton Junior College, where a group of Japanese American friends formed a social circle they called “The Dinks.” In the summer he earned spending money working at a nearby nursery. Transferring to the University of Southern California, he majored in chemical engineering and took a heavy class load while also finding time to be a part of the Nisei Trojan Club on campus. He became the first in the Kobata family to finish college, and then added a Master’s degree.

Post War Gardena

Educational opportunities were but one of the enduring changes in the Japanese community brought on by dislocation during the 1940’s. Starting almost immediately in the fall of 1942, with work picking sugar beets and other agricultural work, those held in camps in the interior of the U.S. could be released for jobs in the defense industries, professional training, or to join the military.

After the war, veterans could use the GI Bill to get an education or purchase a home. In Gardena, a number of those who had worked in agricultural before Pearl Harbor helped establish gardening services. Startup costs were low, and there were an increasing number of homes to maintain.

There were other vocational opportunities as the war industries converted to peacetime businesses. California had become an aviation center during World War II due to its good weather for training pilots and support personnel. Shipyards had ramped up to produce vessels and supply lines for fighting in the Pacific Theater. Now those industries pivoted to serve a growing population as post-war marriages produced a boom of children.

The fields of the Gardena Valley started to grow houses where berries and other crops had flourished. Southern California soon had new freeways, part of the national vision for an interstate transportation system. Nearby, Walt Disney’s idea for a new kind of amusement park took hold. Boomer families would make it a magical destination.

Not every Japanese family from the Gardena Valley came back like Harold Kobata’s did. People who had been released from the concentration camps to work or study in Denver, Chicago, New Jersey and other urban areas found they liked their new surroundings enough to stay. Why go back to the Pacific Coast where they’d been singled out, vilified and then incarcerated? They had heard that homes of returning Japanese families had been shot at or firebombed, and city councils and county supervisors had passed resolutions opposing their return.

No Need To Leave

Gardena and other towns and cities in Southern California seemed to have more returnees than many other places that had Japantowns. The Central Valley particularly suffered a “brain drain” as second-generation Nisei and third generation Sansei sought college degrees at coastal colleges, and jobs in better paying industries than agriculture.

In the Los Angeles basin, there was little need for Japanese Americans to leave the area for better opportunities after the war. Jobs and educational options were close at hand. They resumed their lives, found partners, and started new families.

Ronald Ikejiri is part of the boomer generation, born in 1948 in the Boyle Heights section of Los Angeles and named because of his mother’s fondness for movie star Ronald Reagan. His father had been a “no-no” respondent to the government loyalty survey administered at Tule Lake Relocation Center. So his parents had been sent to the Crystal City Alien Enemy Detention Facility in Texas, probably because his father, a U.S. citizen, had been attending school in Japan during part of the 1930’s. The facility was smaller than the other concentration camps, and different in that it held German and Italian citizens who were living in the United States, about 3,300 total at one point.

When the Texas facility was closed, his parents moved to Redondo Beach, and his father became part of the trend of offering gardening services. The business did well, and with savings of a thousand dollars purchased a home in Gardena in the early 1950’s. “Growing up,” Ron Ikejiri recalls in a 2019 interview, “Japanese parents would talk about camp. I was a Boy Scout, so I figured it was like Boy Scouts or Girl Scouts they were talking about, which was not true.”

Ikejiri excelled in his scout troop and appreciated his youthful experiences. “Growing up in Gardena, I never felt any form of discrimination. Thinking about it, in junior high and high school, Japanese Americans ran the schools. We were active in sports, student government, drama, newspaper, whatever it would be. And so you never felt you were anything, but what you would be. So there was no cap. Gardena was a wonderful place to grow up.”

Ron Ikejiri in turn interviewed one of Gardena’s post-war political leaders, George Kobayashi, as part of an initiative to capture the region’s Japanese American history. Kobayashi was active in local politics as a series of Japanese Americans were elected to the city council and other offices, including the state legislature. Kobayashi recalled that when he attended Gardena High School, more than half of the students were Japanese Americans.

Real Estate Opportunities

The economy of Gardena after the war was in part driven by a real estate boom. Land was relatively affordable, and developers snapped up property on the edges of Gardena and other nearby communities and built houses. Agents marketing those homes were often welcoming to diverse buyers, and so returning Japanese Americans could do something that many of their parents hadn’t been able to do—buy property. Further, the restrictive alien land laws were rolled back in California. And citizenship was offered to first generation Japanese immigrants in the early 50’s who were previously categorized as aliens ineligible for citizenship.

Paul and Hideko Masuno Bannai were right in the middle of the changes taking place in Gardena. A veteran of the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, Paul returned to California and became manager of the Los Angeles Flower Mart before the couple moved their growing family to Gardena. They had faced discrimination trying to buy in other places. Paul became part of the solution, joining the Kamiya Mamiya Real Estate firm, and eventually starting Bannai Realty.

The Bannai’s youngster daughter, Lorraine, reflected on those boomer years in an interview done in 2000 for the Densho Japanese American Legacy Project. “Gardena was about, I think, a third Japanese American when I was growing up…It was very comfortable, I mean there were many people around me who looked the same as I did, who spoke the same broken Japanese as I did, who ate the same foods I did. And on top of that, there were a number of community leaders who were Japanese American.”

Perhaps because of her father’s work in real estate, she became aware of Gardena’s housing dynamics. “There was kind of a like a checkerboard pattern of housing, so there was one community of several blocks that had a lot of Japanese American families and then, the next checkerboard part of it would’t have any, and the next one would…It wasn’t until later that I realized that the reason it was that way was because of racially discriminatory covenants.”

What’s remarkable is that most of the post-war Gardena neighborhoods are still in place. The houses built in the 50’s and 60’s are small by today’s McMansion standards, making them relatively affordable to purchase now. Closer to the city center, there are also areas with homes built before the boom. Today, Gardena ranks lower than the national average when it comes to levels of poverty, and its housing stock is an asset.

Political Clout Builds

Paul Bannai became a stalwart community leader, active in groups ranging from Nisei Veterans Association of Southern California to Gardena Faith United Methodist Church and Boy Scouts.

Lorraine recalls her father running for city council when she was in high school. “We were very much involved in his campaigning. I remember sitting in open cars at Veterans Day parades, going down the street with him and posing for press campaign photos, and we canvassed door to door in the community for him, asking people to vote for him…he had little fortune cookies that has little messages inside that said “Bannai for you in ’72…It was a good experience. I learned about the political process. I met some interesting people. I remember meeting S.I. Hayakawa and Ronald Reagan.”

Paul Bannai served his community in many ways. He became Vice Chair of the Japanese American National Museum board and made history as the first Japanese American in the state legislature, winning four terms representing the Assembly district that included Gardena. He also was the first director of the Commission on War Relocation and Internment of Civilians, whose findings led to Congressional legislation awarding reparations payments to those whose civil rights were violated by incarceration during War World II. The legislation was signed by President Reagan in 1988.

Paul Bannai’s older daughter, Kathryn, was very much involved with the reparations effort as the president of the Seattle chapter of the Japanese American Citizens League. A human rights lawyer, she also devoted years to overturning conviction of Gordon Hirabayashi in 1942 for violating a curfew placed on west coast Japanese and Japanese Americans after Pearl Harbor.

Following in Paul Bannai’s footsteps to Sacramento is Al Muratsuchi, who first became a member of the Assembly in 2012. Muratsuchi spent most of his growing up years on U.S. military bases where his father was a civilian employee. But he became the first in his family to graduate college at UC Berkeley and then got a law degree from UCLA.

Before elected office, Muratsuchi worked as a prosecutor for the California Department of Justice and as Deputy Attorney General. He was a regional director for the Japanese American Citizens League. Focused on education and environmental issues, Assemblyman Muratsuchi is running for re-election this fall, and as he turns 60 early next month.

AsAmNews is published by the non-profit, Asian American Media Inc.

We are supported through donations and such charitable organizations as the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. All donations are tax deductible and can be made here.

Last day to get tickets for our fundraiser Up Close with Connie Chung, America’s first Asian American to anchor a nightly network newscast. The in-depth conversation with Connie will be held tonight, November 14 at 7:30 at Columbia University’s Milbank Chapel in the Teacher’s College. All proceeds benefit AsAmNews.