By Raymond Douglas Chong

(This is part of our ongoing series, Lost Kinjo- a look at the more than 40 Japanese communities that disappeared after World War II. It is supported by funding from the California Public Library Civil Liberties Project and the Takahashi Family Foundation.)

In the San Francisco Bay Region, Japanese Americans (population 435 in 1940) settled in San Mateo’s suburban city Japantown, providing services and working as domestics to the White elite.

Since 1906, the beloved Takahashi Market in downtown San Mateo has served the community through four generations of the Takahashi family. It is known for its iconic musubi (a Hawaiian dish of grilled meat between rice and wrapped in nori seaweed).

San Mateo Japantown

During the late 19th century, the Japanese sojourners and pioneers arrive from Imperial Japan to settle in San Mateo County to farm crops and harvest salts.

The community developed a flourishing Japantown in downtown San Mateo. They faced systematic discrimination by the White establishment. Racist laws denied citizenship to the pioneers. They were segregated to marginal housing downtown by racial covenants in property deeds and homeownership redlining in San Mateo Japantown. They were condemned to menial, unskilled, and domestic labor.

During the pioneer times, restaurants, boarding houses, bathhouses, grocery stores, general stores, community organizations, laundries, and tailor shops catered to a bachelor society. During the Picture Brides era, 1908 to 1924, a Nisei or second generation flourished with young families. Buddhist temple, Christian church, Japanese language school, Boy Scouts troop, social clubs, and sports clubs were part of the neighborhood.

S. Sato and K. Katoaka established Yokohama Laundry (1900). Tokumatsu Hata ran his Hata Merchant Tailor Shop (1901). Tetsuo Yamanouchi opened Imperial Laundry (1908).

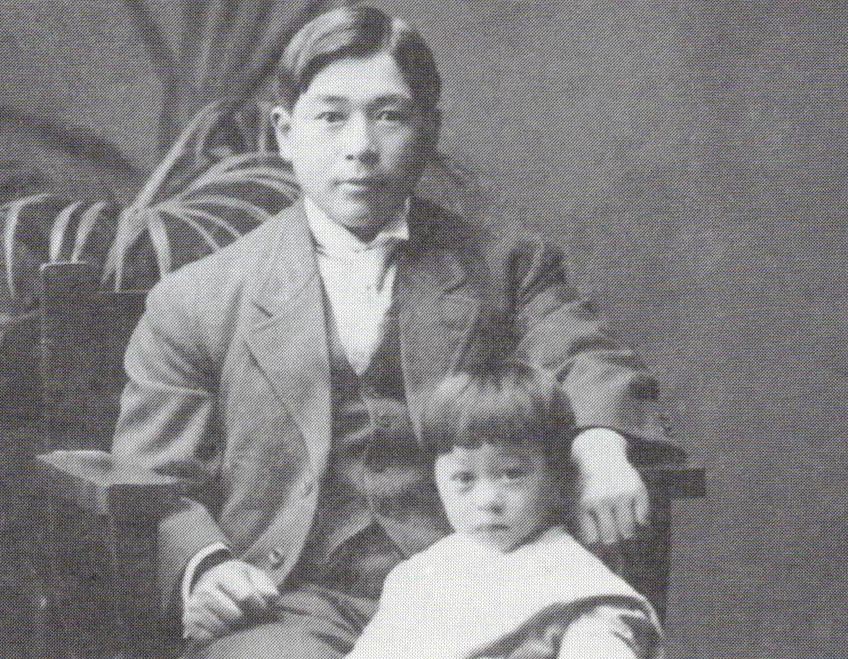

Tokutaro Takahashi opened his landmark T. Takahashi Grocery Store, selling Japanese groceries and merchandise in 1906. He delivered the groceries and merchandise by horse and buggy across San Mateo County. In June 1887, Tokutaro arrived in America from Wakayama-Ken (prefecture), Imperial Japan. He worked as a miner for Alvarado Salt Works in Alameda County. He married Ishiye, a picture bride, in Seattle on October 24, 1906. Tokutaro and Ishiye raised Noboru, son, Masa, daughter, and Kenge, son, in San Mateo.

Under the San Mateo Chapter Japanese American Citizens League (JACL), Gayle k. Yamada and Dianne Fukami wrote BUILDING A COMMUNITY: The Story of the Japanese Americans in San Mateo County (2003). They comprehensively told the development of San Mateo Japantown (1885 to 1942), the incarceration at Tanforan Detention Center and Topaz Concentration Camp during World War II (1942 to 1945), and the painful and fearful resettlement (after 1945).

Many Japanese Americans worked in the floral industry or in San Mateo County’s salt industry. Eikichi and Sadakusu Enomoto, brothers, brought land in 1906 to grow chrysanthemums. The floral industry flourished in the San Francisco Peninsula. Redwood City was known as the World Capital of Chrysanthemums.

Hideyoshi Kashima recalls that time:

As time went on, there were improvements, as far as covering with cheesecloth and black cloth. They call it black cloth because it shaded the plants to fool into [thinking it was] early autumn to shorten the days so that chrysanthemums would form their buds and bloom. But that lengthened the season. So those are the things that I’ve seen develop as my father was growing flowers.

Growing was a hard business even if the Japanese had honed their skills at it. If you had a good crop, it was beautiful. But when business was bad, you could see the stems just leaning over. Some families just left their crop out there because they couldn’t sell out. There were times like that. And it was a one-shot deal, too.

In 1901, the Redwood City Salt Works, and later Leslie Salts hired Japanese American miners in San Mateo County.

Fukami produced the documentary entitled Chrysanthemums and Salt that focused on Japanese American-run chrysanthemums nurseries and evaporation ponds used to mine salt.

The San Mateo Chapter of Japanese Association (1906) kenjinkai held regular meeting. Japanese Language School began in 1916. The Boy Scouts troop was formed in 1925. The Girls Blue Jay Club was formed in 1926. The children played baseball and basketball games in athletic leagues with other Japantowns.

Young Nisei established San Mateo chapter of the JACL on May 11, 1935. They elected Saiki Muneno as the very first chapter president. They wanted to seek their American path from the Issei generation and demonstrate their loyalty to the United States.

On February 20, 1910, the San Mateo Buddhist Temple held an inaugural ceremony. The Temple conducted services at various houses and in rented halls. In 1940, they purchased land to construct a meeting hall.

Issei (first generation Japanese) established a neighborhood Japanese Christian Church in 1924. Dr. Ernest Sturge dedicated a new building in 1938.

At the picnics, I know we took our Japanese bento, nigiri, and everything. They had races for the children – sack races, egg races. And then at the end, the older people would get costumes and wear them and have a parade. Some of the men would dress like women and put lipstick on and everything, which was kind of fun to watch.

- – Tomoko Kashiwagi

I used to ride my bicycle or walk—most of the time I’d ride my bicycle—to [the scoutmaster’s] home and the meeting place was held at the [American] Legion Hall. I think it was Troop 48, and their hall was located on East Bellevue between San Mateo Drive and the railroad tracks… And through the scouting movement, you learn all the necessary things like cooking and knot tying. At least I was exposed to this other area of scouting, which I think even today, people—kids—enjoy scouring and do better themselves.

— Yoneo Kawikita

Ben Takeshita, a Nisei, recalled his growing years in San Mateo Japantown before World War II (Ben Takeshita, interview by Virginia Yamada, March 11, 2019, Densho Visual History Collection).

Virginia Yamada: Let’s get started with you telling us where you were born and when you were born, and the name that was given to you at birth.

Ben Takeshita: Okay. I was born on August 2, 1930. My name was Ben Takeshita. “Ben” is the character used for that means to “study hard.” My parents wanted me to study hard. It didn’t work, but that was a character that was used to make my name. And it’s a Japanese name, not Benjamin, it’s a Japanese name, Ben.

Virginia Yamada: Well, what about your parents? What were their names and when and where were they born?

Ben Takeshita: Okay. My father’s name was Manzo and my mother’s name was Hatsumi, but they were both born in the southern part of Japan in Kyushu, the island of Kyushu, and the prefecture of Fukuoka. And so my father came to the United States probably in the early 1900s, and then my mother came to get married to my father, because my grandfather, who was on my mother’s side, he had come to the United States about 1890 or somewhere in there, working as a farmer. And he met my father and felt that my mother might be a good match for him, who was the daughter of him, so that’s why he called my mother over, and she got here about 1914, somewhere in there, and they got married soon thereafter as farmers in the San Leandro area of East Bay.

Viriginia Yamada: That’s okay. So, what kind of work then, did your father do?

Ben Takeshita: So, at the beginning, then, when he came, he was working as a farmer. But all our kids, siblings and so on were born either in San Leandro or Alameda, somewhere in there. And in 1934, my grandfather had moved to San Mateo to start a landscape gardening business, and so he wanted to go back to Japan in 1934. So, he asked my father to take over his gardening business in San Mateo, so all of us left Alameda and moved to San Mateo to take over my grandfather’s landscape business. So that’s why

Virginia Yamada: Were there other Japanese, Japanese American families in that area?

Ben Takeshita: Oh, yes, quite a few. In fact, they had a Buddhist church there.

Virginia Yamada: What kind of businesses, the Japanese-owned businesses do you remember in San Mateo?

Ben Takeshita: Well, I remember the grocery store, Takahashi grocery store that they had. There were, in fact, two cleaners in San Mateo, the Sunrise and Blue. But those were about the only kinds of businesses, and the rest were either landscape gardeners, that kind of independent contractors.

Virginia Yamada: So, what are some of your first childhood memories, then, of growing up in San Mateo?

Ben Takeshita: Well, we had to walk to school. So, we just walked from where we lived, and walked to Lawrence School, which was a pretty far walk. But we used to do that without any problems. My mother made lunch bags for us, so that’s what we took. So, it wasn’t… nothing that I remember that was frightening or whatever, we just walked. And then when we got to Lawrence School, then many of us Japanese Americans, we played handball, so we would play handball. Then, later on, before the war, some of the girls who were raised in Japan and had an education, they came back to the United States, and they knew a lot of the games that they used to play on dirt. So, we used to do a lot of that kind of, we’d meet on the, what they call Steal the Treasure, which were rocks, and you’d have to go around this area and get inside and get that rock and bring it back to your side. And then if you got tagged, then you’re out. It was primarily playing amongst ourselves, Japanese Americans, and not with the other Caucasians or other schoolmates. In class, we were naturally together and so on, but recess-time and so on, we normally stuck together amongst us Japanese Americans.

Virginia Yamada: So, what was your relationship like with your parents?

Ben Takeshita: My father didn’t say too much, but I think I was a bad boy or had very bad backtalk and that kind of thing, because I remember being tied up and put down in the basement for a while. [Laughs]

Virginia Yamada: From your father?

Ben Takeshita: Yeah, my father and them, so my mother, later on, would feel sorry for me and come and untie my… but he didn’t hit us, but I remember being stuck in the basement several times. So, I must have been a pretty bad boy. [Laughs]

Virginia Yamada: Okay, so that means you probably spoke Japanese pretty well when you were a kid?

Ben Takeshita: Well, the custom was, also, from grammar school we would go to Japanese language school. So, school ended about three p.m., so then after that we’d go to the Japanese language school and spend a couple of hours there and trying to learn Japanese and how to write the Japanese alphabet, phonetic alphabet. So as far as I was concerned, it really didn’t help us. When we had to talk to our parents, we had to use Japanese, because they didn’t understand English, so we had to do that, but we made a go of it, I guess, we communicated. But it wasn’t a fluent Japanese that you would speak in a business forum or whatever, it was just enough to talk to their parents and so on, that’s about it.

Virginia Yamada: Okay, so your parents spoke primarily Japanese?

Ben Takeshita: Yes.

Virginia Yamada: Did they speak more English later on?

Ben Takeshita: My father, naturally, was as a landscape gardener, he had to speak some language, and in fact, he worked as a gardener during the day, and then nighttime he would go wash dishes and so on and do that kind of work. So my father, I remember, would go to work at night after doing his daytime gardening work, and then we would wait for him to come back, because many times he would bring home cakes or desserts that he had at the, when he washed dishes and so on, and they gave him things to bring home. So, we used to wait for my father to come home and have the goodies that he would bring home. Not every time, but then when he did bring it home… and my father was, in a way, a joyful kind of a guy. I remember him, as I said, sometimes I guess I acted, did backtalk or something, because I did something bad to where I was tied up in the basement. But not too many times, but most of the time was a happy kind of an atmosphere, as I remember.

Virginia Yamada: Did he say anything to you when he would put you in the basement like that, or did he just kind of do it?

Ben Takeshita: He just did it. I don’t remember what I did to cause that to happen, but I do remember being put in the basement. And as I said, my mother would feel sorry for us, would come in. And my younger brother and I were the ones, and, as I said, my two older brothers were in Japan, so they weren’t involved in that. I don’t know what I did, but I must have been bad. [Laughs]

Virginia Yamada: So how long did you live in San Mateo?

Ben Takeshita: Well, we lived in San Mateo until the war started and then Executive Order 9066 was passed on February the 19th. And on May the 19th, we had to leave our home and go to Tanforan in San Bruno, California, to start our experience in these camps, so to speak. So, actually, after the war ended, we went back to San Mateo and then I grew up going to San Mateo College and also, from there, we moved to Berkeley and went to UC Berkeley that way. And then when I came to Berkeley, then I started to live in the East Bay, went to Oakland and then now in Richmond. So, until 1956 or something like that, I was living in San Mateo.

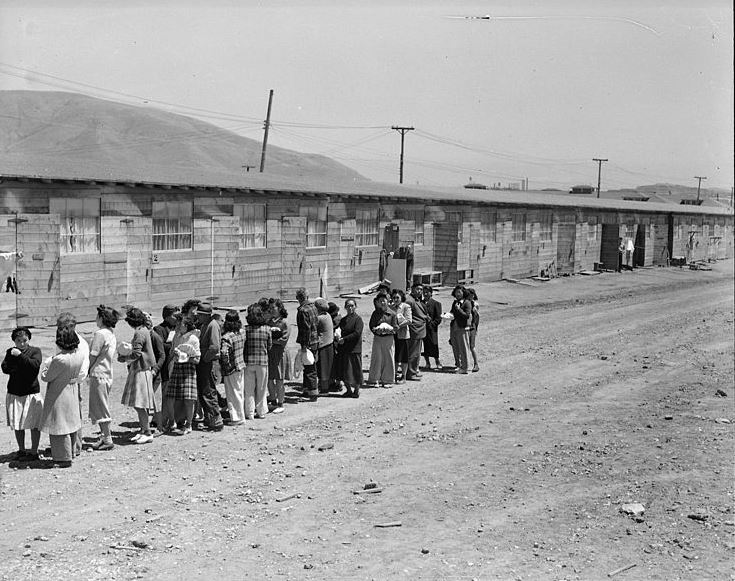

Incarceration at Tanforan Detention Center and Topaz Concentration Camp

President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 on February 19, 1942. He authorized the mass forced removal and incarceration of all Japanese Americans (120,000 total) from military areas on the West Coast. The War Relocation Authority (WRA) crudely imprisoned them in ten concentration camps in the desolate American West and Deep South.

The WRA wrongfully imprisoned the Takahashi Family, Tokutaro, Ishiye, Masa, and Kenge. Tokutaro entrusted his business to his landlord.

On May 9, 1942, the War Relocation Authority shipped the Japanese Americans of Santa Mateo County (a total of 891) to the Tanforan Detention Center. It was located at Tanforan Racetrack in San Bruno, California. The inmates lived in former horse stalls

It’s a sinful waste of energy, ability, brains, and productivity to look up thousands of people and force them to do nothing.

- – Tomoye (Nozawa) Takahashi

“There are two things in this camp that people want more than anything else – good food and toilet paper. With these two essentials in stock, I think that Toni and I are ready to join the ranks of the aristocrats of Tanforan. Thank you very much.”

- – Tamotsu Shibutani

The WRA shipped the Japanese Americans from the Tanforan Detention Center from September 11 to October 15, 1942, to the Topaz Concentration Camp. It was located at a dusty site in the Sevier Desert in desolate central Utah.

The amazing spirit of these people! They were not going to be defeated … in Tanforan, to start with, and Topaz, it was really the spirit of the people … and I think that’s remarkable.

- – Kyoko Hoshiga Mukai

“Ye Gods, it’s a terrible place here. The dust storms are awful—can’t see ahead of you, the rooms are dusty and even closed windows can’t keep out the dust. We eat, sleep, and live in the dust. Golly, how I miss California. I thought our stables in Tanforan were bad, but it’d be heaven if we could only go back. People about me are discouraged and disappointed–they say it’s no place for humans to live.”

– Riyoko Kushida

442nd Regimental Combat Team – Go For Broke

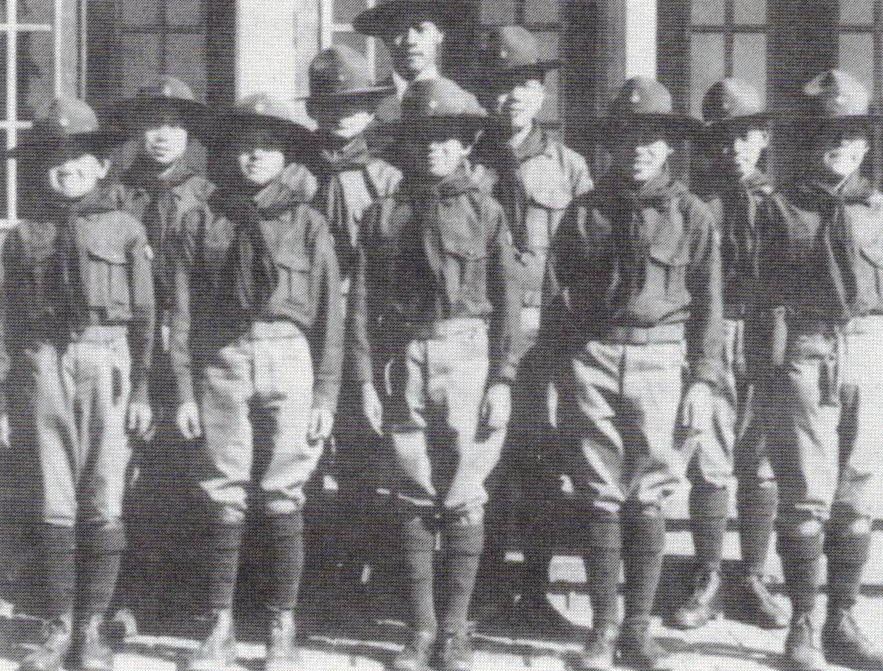

During World War II, the United States Department of War formed the 442nd Regimental Combat Team (442nd RCT), a segregated unit made up of Nisei from Hawaii and mainland concentration camps. They activated the 442nd RCT in Mississippi in February 1943.

The 442nd RCT fought in Italy, France, and Germany, in the Mediterranean Theater of Operations and European Theater of Operations until May 2, 1945, when Nazi Germany surrendered to the Allies. The 442nd RCT and the Nisei soldiers earned five Presidential Citations, over 4,000 Purple Heart medals, and 21 Medals of Honor. Go For Broke was their famous motto.

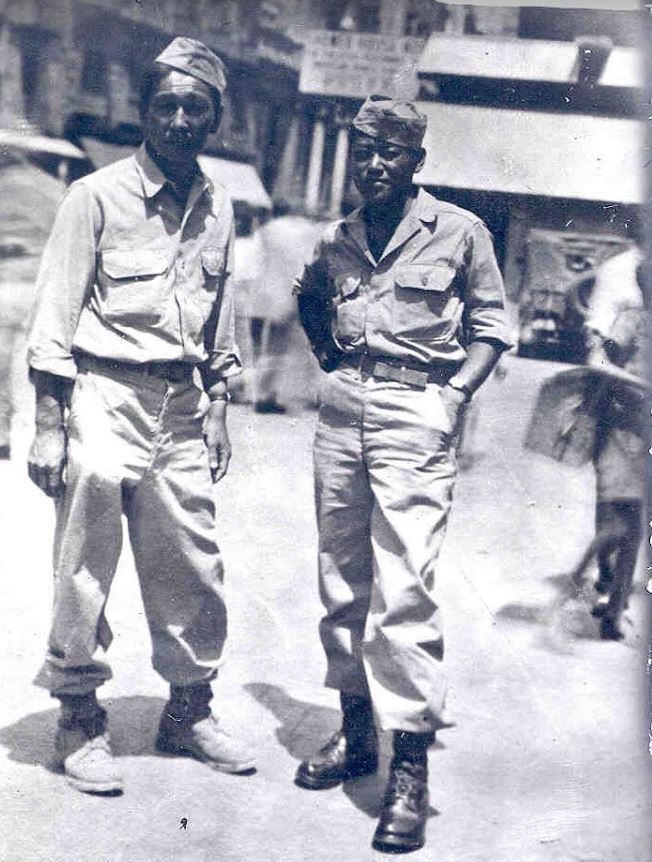

To prove his loyalty to America, Kenge Takahashi, son of Tokutaro and Ishiye of San Mateo. On April 13, 1944, he voluntarily enlisted with the United States Army at Fort Douglas, Utah. He trained at Camp Shelby in Mississippi.

Kenge was deployed as Private First Class (PFC) with the 442nd RCT in 2nd Battalion, Company C. He fought in France in the European Theater of Operations. On March 25, 1945, assigned to the 5th Army, the 442nd RCT arrived at Livorno, a port city on the west coast of Tuscany in Italy.

The 442nd RCT proceeded with the Northern Apennines Campaign (April 1-4, 1945) and the Po Valley Campaign (April 5 to May 5, 1945). Their purpose was the destruction of the German Army in Italy. They combatted along the Ligurian Coast from Massa to Turin to break the Gothic Line.

On April 7, 1945, the 442nd RCT fought in a battle at Massa near Mount Belvedere. Go for Broke National Education Center in Los Angeles wrote about the Po Valley Campaign.

On April 7, the 2nd Battalion pushed toward the wide rolling top of Belvedere. Veteran troops from the formidable Kesselring Machine Gun Battalion battered the attackers. The crack Nazi battalion wasn’t giving up ground. F Company Technical Sergeant Yukio Okutsu broke the deadlock. Twenty-four-year-old Okutsu single-handedly knocked out three machine gun nests. At the third, he captured four men. His heroism earned him a Distinguished Service Cross.

President Wiliam J. Clinton awarded a Medal of Honor to Yukio Okutsu of Hawaii on June 21, 2000, as an upgrade from the Distinguished Service Cross.

The President of the United States of America, in the name of Congress, takes pleasure in presenting the Medal of Honor to Technical Sergeant Yukio Okutsu (ASN: 30103687), United States Army, for conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity in action above and beyond the call of duty while serving with Company F, 2d Battalion, 442d Regimental Combat Team, attached to the 92d Infantry Division, in action against the enemy on April 7 1945, at Mount Belvedere, Italy.

PFC Kenge Takahashi was wounded in action on Mount Belvedere above the City of Massa. He was hit by shrapnel. He received a Purple Heart medal.

Kenge yearned to return to San Mateo. He said, “I wanted to come back to my grassroots. I was so used to everything. I’m proud I did what I did serving in the military and raising a family.”

On November 2, 2011, in Washington DC, the Congressional Gold Medal was presented collectively today to the U.S. Army’s 100th Infantry Battalion (INF BN), the 442nd Regimental Combat Team (RCT), and the Military Intelligence Service (MIS) – also known as Nisei Soldiers of World War. It recognized the Nisei Soldiers’ dedicated service during World War II.

Adam Schiff of California, House of Representative, praised the Nisei soldiers.

It was a thrill to stand next to the brave Japanese-American members of the ‘Go For Broke’ regiments and the veterans of the Military Intelligence Service today as they were awarded with the Congressional Gold Medal, the nation’s highest civilian honor, for their dedication to our country during World War II,” “These remarkable men left a segregated nation to fight and defend an America with no guarantee that their own freedom would be defended in return. These American heroes did defend our freedoms and ideals. Their true heroism lies in how they fought for the values of America – equality, justice, and opportunity – even when those values were denied them at home. And they paved the way for millions of other Americans to wear the uniform today proudly.

PFC Kenge Takahashi, the infantryman, received a bronze replica of the Congressional Gold Medal posthumously.

Resettlement After 1945

In re Mitsuye Endo 323 U.S. 283 (1944), the United States Supreme Court unanimously ruled that the federal government could not confine indefinitely American citizens of Japanese ancestry who were “concededly loyal” in the WRA concentration camps. The War Department issued Public Proclamation 21 that lifted exclusion of Japanese Americans from the West Coast. Beginning on January 2, 1945, the Japanese Americans resettled.

The resettlement was difficult for the returning Japanese Americans as they integrated into American society and the labor force. The Issei and Nisei families had lost their wealth during the incarceration in capital, properties, and businesses. They endured a climate of terrorism.

After Topaz Concentration Camp, the Japanese Americans faced an unknown future in San Mateo.

The Yamaguchi family stored all their things at the Chanteloup Laundry. They [the laundry owners] had given them a storeroom where they stored everything. Nob’s brother Terry was in the Army, so he came to check, and nothing was there. Everything that was stored at the Chanteloup Laundry was moved and stored at the Yamaguchi family house on Second Avenue. They had a garage with [an] upstairs storeroom, and they put everything up there with no door, and anyone could get in there and help themselves and it was not locked up. The house was rented that way. Some things were missing, but most things were there.

—Shizu (Yamaguchi) Tabata

“Coming back, it wasn’t hard for me, but it must have been awful hard for all the older people. It was terrible hard on her (my mother). It was emotional. She broke down everyone in a while. She would break down, not knowing how the future would be.”

- – Kaoru Ruth Saido

When we came back, we were two years behind in school, and I had to learn English again, and that was a stigma that stuck with me for a long time. I went back to Lawrence School where my friends that I had were, and I was ashamed that I was two years behind, so I became very withdrawn and very shy because of that experience. That’s why it was more difficult for me to try and assimilate. I remember our neighbors passing by, and there were more Black families at that time, and they were saying, “The Japs [sic] are here.””

- – Michiko Mukai

In a way, even now, I think, “Gee, when am 1 going to start my regular life?” Because we come back, and l figure, well, I’m going to start whatever career I’m going to go into and all that. But each year, ten years later, twenty years, “Gee, it’s about time I’m phis f start my lift’.” And here I’m eighty years old, and I still never got the point where! could pursue my career. Jr West seemed like with the war; it just went away.

— Shig Takahashi

I felt very bitter because it was the prime time of my life. It was a void in my life. Economically, job-wise, or profession-wise, that ten years was a void in my life between thirty and forty. That’s when all the Yuppies are making all that big money, and here in my life, it was zero. It affected my future: future investments and productivity years. So that was one thing that I lost: my productivity of ten years. Even before that, we had to get ready. We lost our jobs; we went to camp. Coming out, I moved ten times and no jobs, no money, so I had to borrow to start. I had no money to buy a car, no money to buy a house, so my wife went out to do catering. All that was the aftermath of the wartime experience. Life was not easy.

— Tad Fujita

After Topaz Concentration Camp, the Japanese American faces a housing shortage in San Mateo.

When we returned, we had to empty the rooms because we had one bedroom, and we loaned out another bedroom to another family, Mr. and Mrs. Kobayashi. The Ikedas rented one room and did their cooking in their room. Mr. and Mrs. Yutaka Kobayashi had rented their house, so they had to stay with us until their house was vacated.”

- – Mariko (Tsuma) Endo

“Many returned with no place to stay. They had to stay with family friends who were fortunate to have a home. Families with children had to have the older kids work as schoolboys and schoolgirls since there was not enough room for the whole family. They worked in Caucasian homes and did menial chores in place of room and board. The family structure was not a reality until the whole family was able to come under one roof by renting a house or buying one.”

- – Yoneo Kawakita

Many returned with no place to stay. They had to stay with family friends who were fortunate to have a home. Families with children had to have the older kids work as school boys and schoolgirls since there was not enough room for the whole family. They worked in Caucasian homes and did menial chores in place of room and board. The family structure was not a reality until the whole family was able to come under one roof by renting a house or buying one.

– Yoneo Kawakita

After Topaz Concentration Camp, the Japanese Americans faced employment discrimination in San Mateo.

When my parents came back [to the West Coast], they were in their sixties and seventies and come back to nothing. And my brothers are in the service, and their older daughter is in New York, and it must have been terrible. It was terrible. I remember going to visit them in Hayward… the nurseries and hothouses are just stifling and having to work in a place like that and starting all over again.

— Kumiko Ishida

Two hundred and fifty Nisei were there because there was a huge mattress factory at North Beach and all the men had gone off to war and now that the war ended, production started again, but there were no workers. So that was the first job because word gets around that there is a job there. It was the experience of my lifetime because I had never worked in a factory. [You should have seen] the type of people who worked there, compared to all the educated people the Nisei were. Later on, we worked side by side on the conveyor, people who later became bank managers or doctors, they were all there, working together.”

It was written up in all the papers, and the ACLU became involved, and it was a big to-do that this Montgomery Reynolds had succeeded in finding us a home in Baywood…And then the neighborhood, they didn’t go up in arms, but there was certain people in the neighborhood that was threatening to cause trouble because of our purchasing the house. But we did move in and eventually lived there for seventeen years, and eventually were good friends with everybody in the neighborhood.”

- – Tad Fujita

[T]he principal at the end had said very frankly that I had done very good work, but he could not recommend me for employment because the district’s policy was, you know, to hire Whites. And at San Francisco State [College], at the placement bureau-this was in 1952-they said also that they had a contract with the city of San Mateo, and the understanding was that they would send them only Caucasian applicants.

- – Kumiko Ishida

Traces of a Lost San Mateo Japantown

In 2024, one can find traces of a lost Japantown in San Mateo.

San Mateo Buddhist Temple, a spiritual and cultural center, built a new social hall dedicated in March 1952. They completed the chapel in July 1958. Later, they built the Education Wing and parking lot.

Sturge Presbyterian Church offers both Japanese and English worship services every Sunday

San Mateo Chapter JACL was reactivated on October 22, 1946, when they elected William Enomoto as president. The chapter tirelessly fought against civil injustices through prejudice and rampant anti-Japanese hate.

The City of Mateo established the Japanese Garden Central Park. In 1966, Nagao Sakurai, the landscape architect of the Imperial Palace of Tokyo, designed the Japanese Garden. It features a granite pagoda, tea house, koi pond, and bamboo grove.

San Mateo Japanese American Community Center, since April 9, 2003, as a nonprofit organization, primarily serves the elderly Shin Issei. This Center hosts various cultural events and activities, fostering a sense of community and preserving Japanese traditions.

On February 11, 2024, the National Parks Service listed the Yoshiko Yamanouchi House Historic District in San Mateo on the National Register of Historic Places. The property is significant for its association with the Japanese American community after World War II. Yoshiko Yamanouchi, an Issei, owned the Blu White Laundry and led the Japanese American community. It features a Ranch Style house, the Katsura Villa, and a Japanese garden.

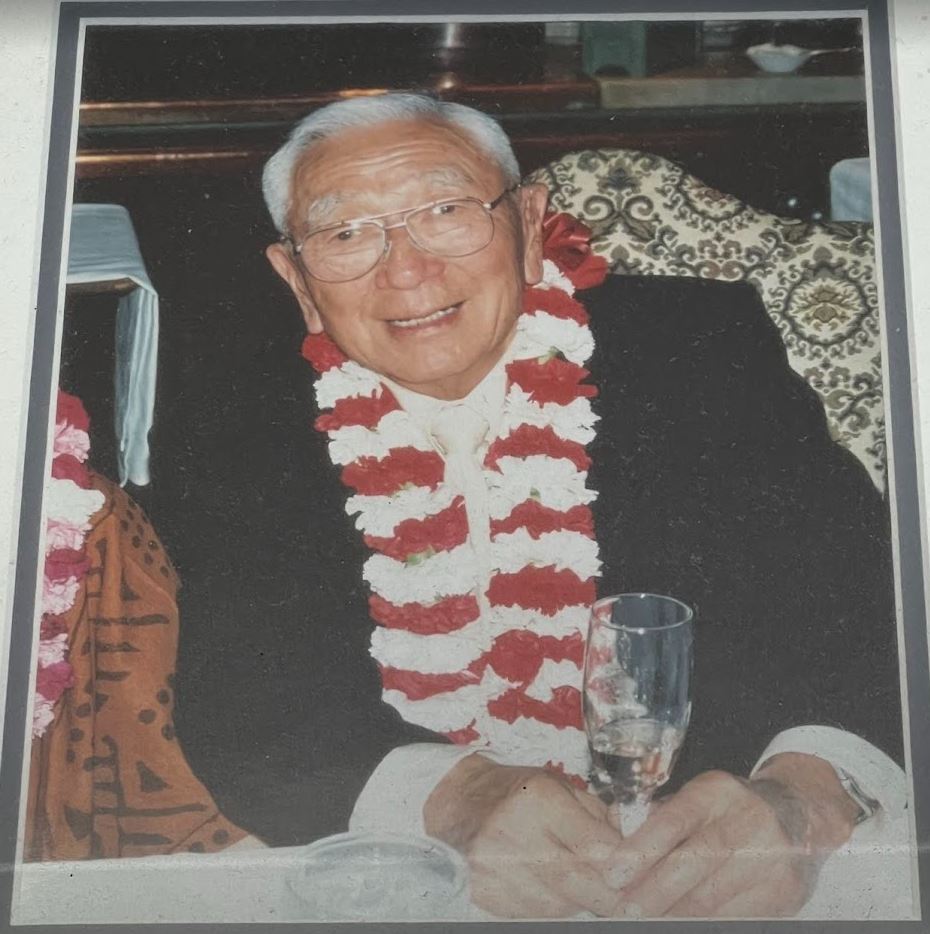

Takahashi Market

Takahashi Market is a historic family-owned market in San Mateo, since 1906 by Tokutaro Takahashi Issei immigrant. The market has been serving the community for over a century, offering a wide range of Asian and Hawaiian foods. It’s known for its musubi, poke, and other Hawaiian-style plate lunches.

- Tokutaro Takahashi: The founder of Takahashi Market, who saw the need for a grocery and general store catering to the Japanese American community.

- Kenge Takahashi: Tokutaro’s son, who served in the 442nd Regimental Combat Team during World War II and later ran the family business.

- Gene Takahashi: Tokutaro’s grandson continues the Market’s legacy with its Asian and Hawaiian products.

- Bobby Takahashi, Tokutaro’s great grandson, is the innovator who runs the kitchen where he creates new comfort dishes

Takahashi Market has been a cornerstone for the Japanese American community in San Mateo, providing Asian and Hawaiian groceries and creating cultural continuity. It has adapted over the years, expanding its products line to include a variety of Asian and Hawaiian foods to meet the needs of a diverse customer base. They are especially famous for their popular spam musubi and poke. Their business model focuses on their loyal and elderly customers and their associated families.

Takahashi Market offers a variety of musubi, fresh daily, including spam, salmon, salmon crawfish, pork lau lau, unagi & crawfish, unagi, loco moco, mochiko chicken, bam, bam (bacon & spam) & ebi tempura, bam and egg, and Portuguese sausage.

They make poke fresh daily including Ahi Poke, Spicy Tuna Poke, Salmon Poke, Tako Poke, and Hamachi Poke.

Their plate lunches include Pork Curry Luau Stew, Mochiko Chicken Curry, Curry Loco Moco, Keoki’s Port Lau Lau, Hawaiian Nachos, Chili, Kalua Pork & Cabbage, Loco Moco, Mochiko Chicken Loco Moco, Chili Loco Moco, Shioyaki Salmon, Teriyaki Salmon, Furikake Salmon, Mochiko Chicken, Furikake Chicken, Mila’s Chicken, Spam & Two Eggs, Aloha Tots,

They sell spam in cans with various flavors: classic, lite, bacon Jalapeno, hickory smoke, maple, tociono seasoning, hot & spicy, and turkey. One can find Diamond Bakery and Kauai Kookie shortbread cookies, Hawaiian Sun and Aloha Maid drinks, and Ono Giant shrimp chips

On its centennial, Tom Lantos of California, House of Representatives, recognized Takahashi Market in Congress on February 8, 2006. He remarked “I urge all of my colleagues to join me in recognizing the Takahashi Market for its 100 years of outstanding achievements on the Peninsula and extend my hope that many more generations of Takahashis enjoy the success and community involvement of the Takahashi Market.“

Gene installed a small commercial kitchen in 2006.

Close

In their “BUILDING COMMUNITY – The Story of Japanese Americans in San Mateo County,” Gayle K. Yamada and Dianne Fukami poignantly closed:

The impact of incarceration and racism was seared into every person, no matter how young or old, and it continues to affect the psyche of Japanese Americans more than fifty years later. The pain may have lessened, but has not gone away. … Many Americans have never learned about the forced eviction and incarceration, and still others cannot believe it every happened.

But it did happen, and it can happen again – maybe not to Americans of Japanese ancestry but maybe to some other group of people who become victims of fear and public hysteria.

We are still at risk. There is still work to do.

Takahashi Market symbolizes the gaman (perseverance) of the Lost Japantown in San Mateo. The Takahashi family display a tremendous resilience for one hundred and eighteen years. Gene deeply evokes the impact of his beloved Takahashi Market:

Since 1906, four generations of our family have continued the legacy of Takahashi Market. We are proud to have served the Japanese and Hawaiian communities for so long. And we deeply appreciate the love and support we have received from our customers.

– Gene Takahashi

AsAmNews is published by the non-profit, Asian American Media Inc.

We’re now on BlueSky. You can now keep up with the latest AAPI news there and on Instagram, TikTok, Facebook, YouTube and X.

We are supported by generous donations from our readers and by such charitable foundations as the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

You can make your tax-deductible donations here via credit card, debit card, Apple Pay, Google Pay, PayPal and Venmo. Stock donations and donations via DAFs are also welcomed.

This story makes me want to visit San Mateo’s Takahashi Market. Thank you, Ray!

This article sheds light on an often overlooked but deeply significant aspect of Japanese American history in the San Francisco Peninsula—chrysanthemum farming and salt mining. It’s fascinating to learn about the contributions and resilience of Japanese American communities, especially in areas like the Peninsula, where their cultural and economic impact helped shape local industries.

The piece does an excellent job of exploring how these farming and mining endeavors were more than just economic activities; they were a means of survival and a way to preserve cultural heritage. The dedication of Japanese American farmers and miners during times of hardship, particularly in the face of discrimination and the internment camps during World War II, is a testament to their strength and perseverance. These industries not only provided sustenance but also allowed for a deeper connection to their cultural roots and sense of community.

It would be interesting to dive deeper into how these industries influenced local culture and community life in the Peninsula. How did these Japanese American-run businesses shape the local economy, or interact with other immigrant communities in the area? Additionally, learning more about the legacy of these businesses—are any of the farms or mines still in operation today?—would help highlight how these early efforts continue to shape the region.

Overall, this article offers an invaluable glimpse into a rich part of American history that often goes unrecognized. It’s a powerful reminder of the strength, resilience, and contributions of Japanese Americans, and how their legacy is interwoven with the cultural fabric of the San Francisco Peninsula. It’s stories like these that help paint a fuller picture of American history and enrich our understanding of the diversity and complexity of this nation.