By David Hosley

Cortez Growers Association Celebrating 100th Birthday in 2024

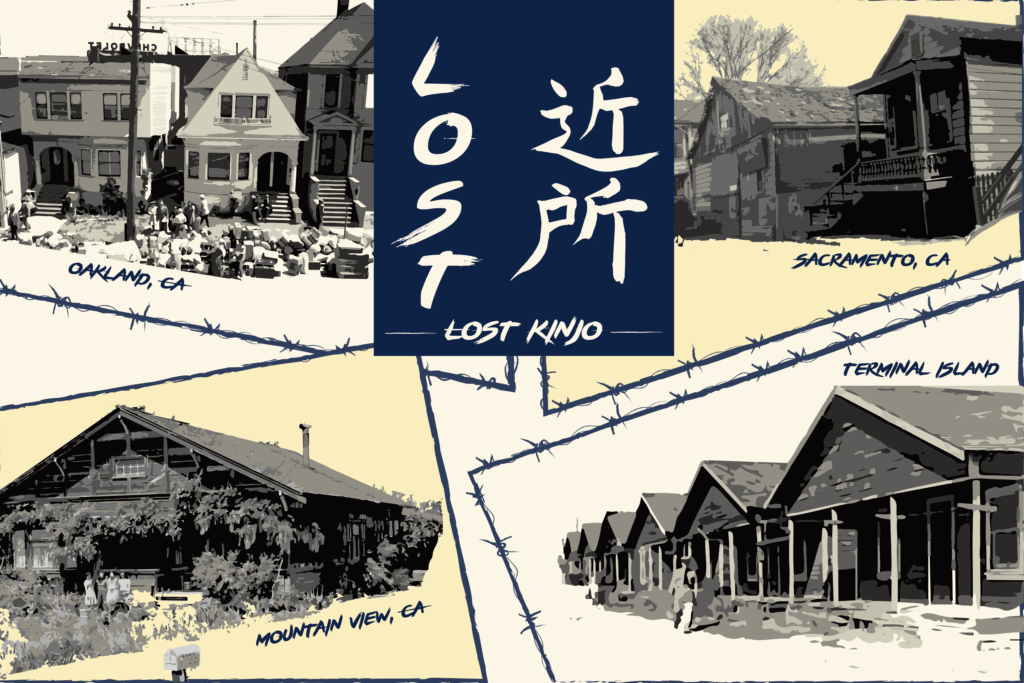

(Editor note: Lost Kinjo is a year-long project funded by the state of California and the California State Library’s California Civil Liberties program and the Henri and Tomoye Takahashi Charitable Foundation. We take a closer look at the more than 40 Japanese American neighborhoods in California that disappeared after World War II.)

Japanese immigrant farmers in California’s Central Valley came together a century ago to start the Cortez Growers Association, which aided in forming a partnership during World War II that protected their property when it seemed all might be lost.

The association fostered cost savings and new markets for its members in the 1920’s and through the Depression. And in its infancy built relationships with other local leaders who faithfully oversaw their assets in a unique trust while the owners and their families were held in concentration camps in the interior of the country after Pearl Harbor.

Today, the Japanese American community in Cortez has faded from its heyday in the 1930’s, but the unincorporated area in northern Merced County still has a Japanese American presence that will be celebrated when the growers association founded in 1924 marks its special anniversary later this year.

Last of the Abiko Colonies

While there had been a small number of Japanese immigrants settling near the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe train line in north central Merced County in the 1910’s, the purchase of 2,000 acres of land by Kyutaro Abiko just after World War I ended the catalyst for development of Cortez.

Abiko was an early immigrant from Japan, having arrived in 1885. He was an entrepreneur who did especially well as a middle man between farmers seeking labor crews and young Japanese men from farming area in southern Japan, which was experiencing social upheaval and an economic depression. He also had started a Japanese language newspaper in San Francisco, and had used its significant outreach to attract newcomers to colonies he’d started in Livingston in 1907 and Cressey in 1918.

The initial colonies around Livingston, about eight miles away, provided an economic and social center for the newer ones to the east. Abiko’s vision was being realized, and in 1919 Cortez moved forward.

The colony around Cortez was again divided up into 20 and 40 acres parcels of sandy soil. Families were formed as first generation Issei returned to Japan to find a wife, or sent a photo and met their intended at a West Coast port. The grooms had something special to offer—they could buy their land directly from Abiko, and thus were less likely to be renters or field hands like many of the initial Japanese in California were.

Fostering Opportunity—The Cortez Growers Association

With crops coming in on a regular basis, and a host of infants being born in the Cortez area in the early 1920’s, some of the Japanese farmers started talking about ways to improve their business outcomes. Those conversations turned to action in early 1924, when a handful of farmers established the Cortez Growers Association on April 18th. Nenokichi Morofuji, Seitaro Yoneyama, Yonekichi Kuwahara, and Zenshiro Yuge wanted an agricultural cooperative, similar to ones they had known in Japan, which could obtain better prices on products to improve crop yields and reach new customers for their grapes, strawberries, carrots, eggplant, onions and other truck crops.

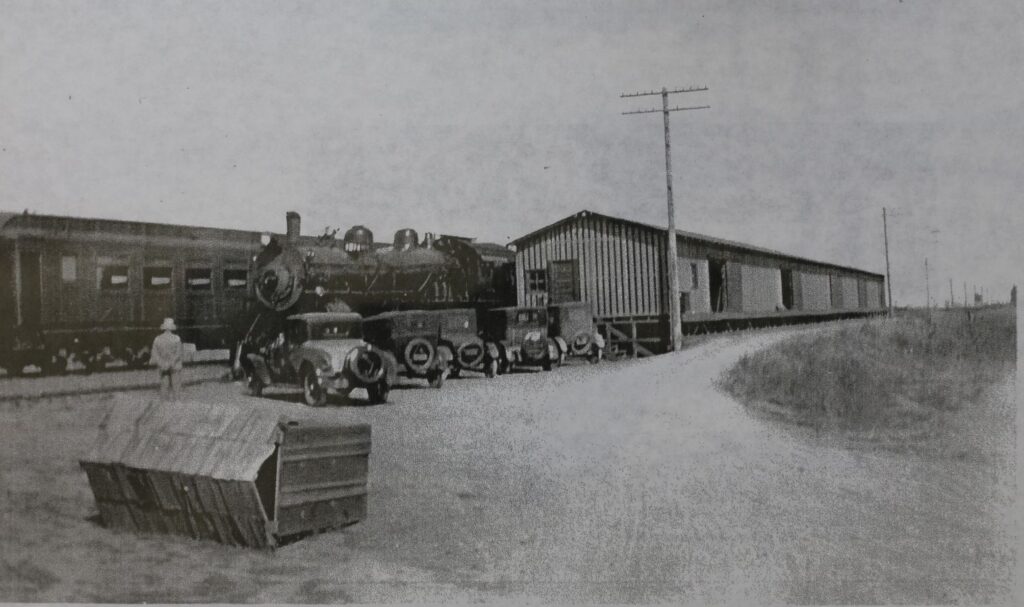

It cost $50 to join the CGA, and by the end of the year, seven more members had joined the founders. The association built a packing shed which would aid in shipping by train, as well as distribution within Central California. The shed was enlarged the next year.

The Cortez Growers Association was initially overseen by part-timers for the harvest season, but in 1932 Sam Kuwahara became its first full time manager. He was just 22 and had been doing bookkeeping. One of his first moves was to purchase a truck that increased access to customers in the San Francisco Bay Area. Having an expanding economic impact meant more local jobs, and so the town of Cortez grew. But it also meant more business for nearby Livingston, and Turlock, both bigger places with a greater variety of stores, not to mention movie theaters.

As families added children, there was more demand for educational services as well. The Japanese American kids, the Nisei generation, became a significant portion of the students attending public schools serving northern Merced County. The majority of Cortez children initially attended Ballico Grammar School, two or three miles away, depending on where your farm was. Those who lived closer to Vincent Road attended Vincent School near Delhi. Kenso Miyamoto, in an oral history recorded in 2002, recalls Vincent was a two-room building, with fewer Japanese American students than Ballico. “Everybody was nice. We had a great time. I went there for eight years.”

Miyamoto observes that his father had foresight and determination. “Father had the say so, Mother went along. “Their advice was basic. “Be honest. Be good to your brother and sisters.” The Cortez teens would go on to Livingston High School. “In our days, in high school, there were a lot of Japanese in Livingston-Cortez area. We were used to the Caucasians most of the time. We weren’t on a segregated basis.” But it was understood, if not said, that there was no interracial dating.

Kenso Miyamoto took a practical approach to his classes at Livingston High. “I was very interested in business.” He took typing and bookkeeping and started working for the Cortez Growers Association, which was weathering the storm of the Depression. For income earned by Miyamoto and his siblings, a little spending money came out, but the bulk went to support the family.

In the 1940 U.S. Census, Township #5 included the towns of Livingston, Cressey, and Cortez. While the population in that area was 8,406 residents, about 600 lived in the Abiko colonies, or 6% of the total.

Unforgettable Wedding Reception

Sam Kuwahara had been leading the Cortez Growers Association for almost a decade when he married Florice Morimoto in the spring of 1941. He was 30 and she was 22, with a year of college in hand. Both were from farm families. They had put off their wedding reception until after Thanksgiving, when the harvests were over and their family and friends could more easily attend.

Today there is a scholarship in Sam and Florence’s name.

They arranged a place to hold it in Merced, the American Legion Hall, setting the date for December 7th. Catering was arranged from a Chinese restaurant. But the Sheriff’s Office called before the reception had started with the news of the attack in Hawaii. The location was moved to Cortez, perhaps because it was thought to be safer. The food was taken along, too. When they got there, and it became clear the anticipated happy day was ruined, the party was cancelled and guests were offered meals to take home.

Any concerns for safety were well placed. The Central Valley of California was home to some of the most virulent opposition to Japanese immigrants, particularly when it came to moving above working as hired field hands or renting farmland. Merced County had some of the highest rates of agricultural land ownership in the country by Japanese and Japanese Americans thanks to the colonies started by Kyutaro Abiko. Japanese Americans controlled less than 4 percent of California’s farmland in 1940, but they produced more than 10 percent of the total value of the state’s farm resources.

It’s hard to tell how much of the maltreatment of Japanese immigrants and their children was based on weakening economic competition. Merced County had formalized opposition two decades earlier, forming the Merced County Anti-Japanese Association, whose president was Elbert Adams, the publisher of the Livingston Chronicle. The association’s leadership included a number of leaders from local farm bureaus. Merced County is the place where a billboard was constructed saying “No More Japanese Wanted Here,” in the 1920’s. Now, with America at war with Japan, it seemed they were not wanted at all.

A curfew was put in place, and travel greatly restricted for residents of Japanese heritage, citizen and alien alike as 1941 came to a close. Cortez residents could still go shopping in Turlock or Livingston, but 10 miles from home was the limit.

Kenso Miyamoto was in an unusual position, in that based on age he was required to register for the draft in October of 1941, and had received a very low lottery number. But when a local doctor gave him a physical, he received a “flat feet” deferment. So on December 7th, he wasn’t in uniform but working on that Sunday morning, hustling beyond his Growers Association office job to pick up extra money packing carrots. “What could Pearl Harbor be?” he wondered. “We didn’t know.” And so he went back to finish the day’s task. “There wasn’t too much discussion. We were in a quandary.”

The Army soon had plans for him, though, for in January of 1942 Miyamoto got reclassified to 1A. On February 13th, he took a government chartered bus from Merced to the Monterey Presidio. He was the only Japanese American on board. Miyamoto came across two others at the induction center. Even though he worried it would be a hardship on the Cortez Growers Association, he remembers being ready to serve. “Abide by the law and do the best you can.” All three of the Japanese Americans got sworn in together.

Executive Order 9066 Triggers Innovative Trust

There was a great deal of uncertainty, but the efforts of the first generation of Japanese immigrants had built infrastructure, trust, and leadership skills among the community of farmers. On March 9, 1942, several Cortez Growers Association members met with Livingston and Cressey farmers to consider acting in concert to protect the property Japanese and Japanese Americans owned in northern Merced County. The same day, the U.S. government established penalties for those who did not comply with orders to assemble and be incarcerated at regional holding places. Public Law 77-503 created fines up to $5,000 or a year in prison.

On March 18th, The CGA membership met and appointed eight men to firm up a legal structure that would protect the farms of their members. The two Livingston organizations did the same. Together, lands that Abiko’s companies sold to immigrant farmers were protected by a trust that held their deeds and acted to identify tenants to keep the land in use. In some cases, the manager of the trust and his board, all of them Caucasian business leaders from the area, hired someone to operate farms at their direction. Howard Taniguchi described how it worked in a 2003 interview, detailing the communication between farmers held near Amache, Colorado and the trust officers back home.

“My Dad did a lot of correspondence because he was on the board of Cortez Growers Association, telegrams and letters.” He added: “We never lost our property, because someone took care of it. It was rundown, but at least it was there.”

Taniguchi and most of the Japanese and Japanese American Cortez area residents, including Sam and Florice Kuwahara, were registered at the American Legion Hall on 16th Street and taken by bus to the hastily built structures on the fairgrounds. It has been but three months since their ill-fated wedding reception.

“The Merced Assembly Center was a hell hole,” Mark Kamiya recalled bitterly. “Black tarpaper barracks attracted the sun. It was stifling hot, just like an oven during the day.”

There wasn’t a lot to do for young and old alike. It was such a change for people who had done the physical labor necessary to grow food that fed their families during the Depression and gave them a small profit in most years. Now they were idle.

Classes were started, some recreational, some a disjointed variation of elementary school. The teenagers had a lot of time to hang out with their friends. There were some sports to play, with teams representing towns in which they no longer lived. There was a desultory graduation for those seniors who had missed the last few months of their final year of high school.

The Cortez Growers Association’s Sam Kuwahara was chosen as a leader of those incarcerated, described as the Ward “D” Officer on a Divisions and Personnel list issued June 24, 1942. He also was named Commissioner of Safety, overseeing the evacuees who saw to fire protection, curfew observation and other aspects of safety. He reported to White civilians hired by the War Relocation Authority.

At the end of the summer, almost every one of those held at the fairgrounds was moved by train to Colorado, where the biggest concentration camp in terms of acreage had been built. The Granada War Relocation Center, as it was official titled, had a total of 10,000 acres. Only a small footprint, about one mile square, had buildings. It was known by those who were incarcerated there as Camp Amache.

Almost immediately, the disbursement of those uprooted from the western U.S. began. Hundreds of evacuees volunteered to pick the local Colorado crops, which addressed a severe labor shortage since many men working in agriculture there had joined the war effort. In that first winter of 1942-43, many of the Californians suffered because of the cold and winds which swept through the barracks and fields. The Cortez farm families and others from the Central Valley didn’t have clothing for the freezing weather.

The nearby Arkansas River and other water sources helped provide bumper crops inside the camp in 1943 and the surplus, including onions, corn, potatoes, was shipped to other camps.

Release and Dislocation

There was also opportunity to be released from Amache to attend college or other educational institutions. Others could work in agriculture. Mark Kamiya noticed a sign in the compound seeking help outside of camp. He applied and was released to a farm 100 miles away in September of 1942. He was picked up in a beet truck. “We were herded like cattle,” he remembered, to fields where he topped sugar beets by hand. “It was backbreaking work,” with the only place to bathe being a lake. They had to buy their own food. Cooking facilities were rudimentary. Later, the lake froze over.

Kamiya said he then picked cantaloupe for three months before returning to Amache for a week. A new job took him to Kendall, Nebraska to work for 50 cents an hour to sort potatoes. The drudgery inspired him to apply to college, and he was surprised to be accepted by Brigham Young University, later transferring to the University of California in Berkeley.

After the government administered a disastrous survey that was supposed to measure loyalty of those incarcerated to the nation that had taken away their freedom in violation of the U.S. Constitution, a number of those who refused to fill it out, or failed to pledge loyalty were sent to Tule Lake where dissidents were concentrated. In return, Amache got a group held in northern California who didn’t mix well with the relative cohesive evacuees in Colorado, who were smallest in number of all the relocation centers.

For the men of service age who had pledged their allegiance to America in the survey and said they would serve, a good number of them almost immediately received draft notices. Others volunteered and joined them in an all Japanese American military unit that served with distinction in Europe. Some who demonstrated strong Japanese language skills joined the Military Intelligence Service and prepared for duty in the Pacific Theater.

By 1944, the U.S. government recognized that Japanese would not be invading the Pacific Coast, and spurred further by court cases upholding the civil rights of Japanese who had sued, took steps to close the concentration camps.

Mark Kamiya indicated in a 1982 interview that there was a deep sense of no matter how tough things are, you must pull through it. Coming out of concentration camps, being far from everything you know on release from imprisonment, or returning from fighting overseas, that inner strength was critical to recovery. “Within the Japanese community,” he reflected, “there is a word for duty or honor, that we have to fulfill these things. It is still with me.”

Fading Of Japanese Communities

The children of the Nisei generation, if their parents had returned to Merced County and its agricultural economy, lived a very different life as boomers. Yes, if you lived on a farm, you might be expected to do chores before or after going to school and help with planting and harvests. Nancy Sakaguchi told AsAmNews her husband Rodney said he drove a tractor on Santa Fe Drive when he was so young he could barely see over the steering wheel, which caught the attention of a California Highway Patrolman.

Some of the Cortez residents stayed in tents next to the Cortez community center while waiting for leases to expire on farms that had been rented by the trust. Services at the Presbyterian Church and Buddhist Church resumed. The Japanese American Citizen League Cortez chapter reorganized, and annual picnics for the community were held, along with Obon festivals to honor ancestors. Later on, Japanese classes were resumed at the Buddhist Church, and in another sign of coming together, they were taught by the Presbyterian’s minister.

For those who were able to plant crops, there wasn’t income until the vegetables and fruit could be harvested. The Growers Association resumed operations, with Sam Kuwahara back at the helm until 1946. He felt drawn to farming full time, and was succeeded as manager in 1947 by Ken Miyamoto, who had also come back to CGA.

Ann Kubo Osugi remembers Cortez residents in the decades after the war coming together to support each other. Her father Shizuma Kubo had started to plant new almond trees one year during the 60’s, when one of his parents died unexpectedly. While Shizuma was taking care of family matters, neighbors pitched in and planted the rest of the orchard.

Cortez Growers Association was not just about business. It was also a place where farmers gathered on a regular basis to talk about growing conditions, commodity prices, and perhaps sports or local politics. CGA was, in short, a community center as well as a processing and packing facility.

While playing sports and cheering on teams at Livingston High, Sakaguchi says there was always a focus on getting further education, whether that was Modesto or Merced Junior College so you could save money by living at home or going directly to a four-year school. “It was expected of all of our generation to go to college.”

She attended Fresno State and got a degree focusing on communicative disorders, which led to a long career teaching the deaf and hard of hearing for the Merced County Office of Education and also in the Ceres Unified School District. But she reflects on others in her high schools, especially her third-generation male classmates. “Boys went after engineering and other degrees. Most of them didn’t come back to the farm.” The jobs they studied for were primarily in urban regions along the coast, with technology starting to bloom as a major economic driver in California.

There were also other trends that drove the decline in family succession on farms. Sam Kuwahara cited one in a 1982 interview. “The trend of all farming is fewer and larger farms I think that will be a part of this area, too.”

Mark Kamiya recalled the phone call when his son shared that he wasn’t going to make his living on the family farm. The young man wanted to be a lawyer. “I was hoping he would take over the farming enterprise. One hundred sixty acres plus 60 leased. I thought it was worthwhile for a family or two. I was hoping he’d take over. There wasn’t much I could do. He went with the law, and I sold out. It was sad, something you put your life into.” Kamiya’s daughter wasn’t interested, either. Just ten acres were retained for retirement living.

What farms in the region were producing was changing a lot as well. Peaches started to fade over time, in part due to closure of nearby processing plants. The original mainstays of other fruits and vegetables shrunk as well. Almonds trees replaced some of the declining crops, and the Cortez Growers Association leadership foresaw and adjusted to the trends. Its board voted to construct a new plant in 2005, which significantly expanded capacity to hull and shell the nuts.

The CGA plant today is all about almond processing. On one 24-hour shift towards the end of 2023, 676,628 pounds went through the association’s machinery, a new benchmark. The record for pounds per hour was also smashed.

The committee planning the 100th anniversary celebration on June 24th in Modesto includes CGA staff and current and former board members. They are: Art Gardner, Michelle Hammond, Galen Miyamoto, Victor Roman, Victor Yamamoto and Dennis Yotsuga.

The Cortez Growers Association is led by general manager Dave Thiel. He, like other managers before him, knows the industry and the community well. He’s been with CGA for 22 years, and its head since 2016. His plant operations manager, Victor Romer, has worked at the association since 2001, and held his leadership position since 2010.

There’s now an interesting connection between almonds and the Japanese. Twelve percent of California’s almonds are exported annually to Japan, the number two international customer behind Germany. Almonds grown on land in California once farmed a hundred years ago by Japanese immigrants now go to 88 other countries as well.

This summer, during 4th of July week, the town Oban Odori activities, sidelined by COVID for two years, are coming back 101 years after the first Oban was held in Cortez. It comes at the end of Tomodachi Gakko, a week of fun and learning about the Japanese culture for youngsters, some of it led by volunteers who once took similar classes in the town. Taiko drumming will likely be heard—it’s taught at a nearby elementary school, and there are adult taiko groups elsewhere in the region.

A Buddhist service will be held that week, one of four times a year in-person worship takes place in Cortez. The remaining times are virtual now, once a month. The Presbyterian Church is long defunct, its Sunday school first shut down due to having no children in the dwindling congregation. The Cortez Japanese American Citizens League chapter has faded away, but there’s an annual dinner at the Merced Fairgrounds around the Day of Remembrance each February where the entire community is welcome.

Nancy Sakaguchi still lives on a portion of Sakaguchi Farms. She, along with Ann Kubo Osugi and Mikala “Miki” Baba, are writing a book about the Cortez Growers Association and the community in which it plays such a central role. The book should be ready for the CGA’s anniversary dinner.

“Because I’m working on the book,” says Sakaguchi, “ when you look back at what’s been done, it’s a rich life. You don’t realize the magnitude of what they went through to give you an education and foster what you’ve achieved. I’m grateful.”

AsAmNews is published by the non-profit, Asian American Media Inc.

We are supported through donations and such charitable organizations as the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. All donations are tax deductible and can be made here.

Please follow us on Instagram, TikTok, Facebook, YouTube and X.

Love these articles about the little known and rural Japanese American communities. Thank you Mr. Hosley! I remember seeing you at the taiko concert held many years ago in Mt. Shasta City (Shasta Yama).

The way we treated the Japanese is horrible