By David Hosley

(This is part of our ongoing series, Lost Kinjo- a look at the more than 40 Japanese communities that disappeared after World War II. It is supported by funding from the California Public Library Civil Liberties Project and the Takahashi Family Foundation.)

El Centro hosted one of the last Japantowns to be established in California, but that’s because the Imperial Valley was so remote, hot and dry that only the taming of a wild river and laying tracks across sand dunes made it possible to grow food and prosper as first-generation immigrants.

The Japanese community reached critical mass for only three decades, cut short by racism and changes in government policies. “There was a significant population before World War II,” Tyler Brinkerhoff, archivist of the Pioneers’ Museum in Imperial, tells AsAmNews. “But just a few returned afterwards.”

Transforming A Desert Sink

A combination of harnessing the Colorado River and improving transportation modes made one of the least habitable places in the United States into a highly productive source of vegetables and fruit in just a matter of years in the early 20th century.

Almost all of the Imperial Valley is below sea level, in parts more than 200 feet below. El Centro is the largest city in the U.S. below sea level. Its unique climate features eight hours of sunlight in the winter, the most in the country. Parts of the valley can freeze in the early months of the year and has a record of 121 degrees in summer.

Japanese immigrants to the West Coast were recruited in the 1890’s to work on extensions of the Southern Pacific railroad, including the Sunset Route leg from Yuma to Los Angeles, and a spur that went south from Imperial Junction to Mexico.

The spur had been completed by 1904, bringing with it several thousand new residents. Among them were three Japanese. But almost immediately there was a break in the Alamo Canal, a 14 mile conveyance that connected the Colorado to the head of Alamo River. Construction of the canal had started in 1900 and it was first used the next year. But problems with control gates and erosion got out of control and formed the Salton Sea. The developer ran out of solutions and funds to pay for them, and Southern Pacific had to step in and set things right with the water supply.

Young, Single Men

By 1907, according to Planted In Good Soil author Masakazu Iwata, that number had risen to 16 Issei farmers in Brawley and more to come. Three years later the Japanese population in the valley was 80. The first Japanese religious entity in the region was founded in 1913. It was a Christian Church.

Tim Asamen, coordinator of the Japanese American Gallery at the Imperial Valley Pioneer Museum, tells AsAmNews the bulk of immigrants over the next two decades came from southern and western Japan, especially Okinawa, Hiroshima and Fukuoka prefectures.

The climate of the region was an exceptional advantage, once there was a reliable supply of water for irrigation. The Imperial Valley warmed up earlier than most growing regions in the West, and the railroad connections both east and west opened up metropolitan markets—El Paso, Dallas and Houston in one direction, San Diego and Los Angeles in the other.

By 1914, Southern Pacific was shipping four thousand railway cars a year of cantaloupes to urban parts of the country, aided by improvements in refrigeration that made it possible to reach Chicago, New York and Seattle with fresh fruit and vegetables.

New highways put El Centro on the map for motor cars and trucks, adding more options for getting produce to consumers. Improvements in infrastructure were rapid, with construction of drinking water and sewer systems. That same year, just before World War I, the Imperial Valley boasted 25,000 residents, including more and more Japanese immigrants, most of them young single men.

Opposition To Asian Immigrants

Not everyone welcomed the newcomers. Once recruited after the Chinese Exclusion Act of the 1880’s, Japanese immigrants had been essential to California’s agricultural growth at the turn of the century. Mostly from the southern part of Japan, they brought agricultural skills that included planting, pruning and irrigation. They had come to America to seek better wages, reportedly twice as much as they’d been making. In part, antipathy aimed at the Chinese had been transferred to the first generation, known as the Issei.

The Japanese Association of America was founded in 1900, in part to advocate for continued immigration and rights for those now in the country, but opposition was growing. A quasi government pact, called the Gentlemen’s Agreement, was reached in 1907 and 1908 to ease tensions. The U.S. would agree to allow wives, children and parents of recent immigrants from Japan, while the Japanese government would deny passports to Japanese males who wanted to work in America.

To get around the restrictions, men who had been been in the U.S. long enough to set aside some savings entered into arranged marriages. Some of them were done in absentia after exchanging pictures with the prospective bride. Others met their intended at ports on the coast from Seattle to San Francisco and participated in mass weddings nearby. In other cases, immigrant men returned to Japan, married there and then brought the new bride to America.

A series of alien land laws passed in the California legislature restricted ownership, but had been amended in 1913 to allow short term leasing. Other western states adopted copycat measures. Increasingly there was federal interest in restricting immigration.

Increasing Presence in Imperial Valley

Zensuke Uchimiya was one of the early Japanese settlers in the Imperil Valley. He was from Iwata, not far from Mount Fuji in central Japan and had been trained as an electrical technician. Aboard the Maru Tosa, he arrived in Seattle in March of 1907 with 60 dollars, stating he was going to San Francisco. He was 22, and would take more than a decade before he earned enough money for an arranged marriage to Ren, a woman from his hometown. She arrived in San Francisco in the fall of 2018 at age 28.

Their first child, Yuichiro, was born in El Centro in 11 months later. His first elementary school teacher couldn’t pronounce his name and gave him the name of George. In a 2007 oral history, Yuichiro “George” Uchimiya provided details of his growing up in the Imperial Valley with four siblings—sister Noboku and brothers Joe, Roy and John.

Like almost all of the Japanese farmers in the region, the Uchimiya family lived on rented land. George said his father initially focused on lettuce and melons, but moved north to Niland to grow tomatoes on about 10 to 20 acres. He said they moved every few years “so land could rest.” As Zensuke prospered, he could rent more land, later farming 70 acres of melons further south in the valley.

“I went to school, but I had to work around the farm, too.” He began his elementary education at Jasper Elementary, built in 1906, but continued at Mt. Signal and then Westside in El Centro. He split his high school days between El Centro High and Calipatria in the northern tip of the valley, playing football, baseball and basketball at 5’ 6” and 160 pounds. “There were a lot of Japanese,” he noted, “so we didn’t run into too much discrimination.”

Before he had an operator’s license, George’s father had taught him how to drive a tractor. The Uchimiya children grew up eating a lot of fermented soy beans, and farm families had chicken coops to provide eggs and meat. Most kept cows as well. Fish was delivered to local stores once a week from San Diego.

In the summer, as soon as crops were harvested, the family would pack up for a month or more and go somewhere cooler. They often rented a house in the San Diego area, or went camping. Interstate highways were being upgraded in the 1920’s, including Imperial Valley, and getting to coastal California was a smoother and faster trip.

Building Community

Ren Uchimiya had been a teacher in Japan, and George remembered his mother instructing children using a Japanese curriculum at Saturday school in Niland. First generation parents felt it was important for their children to learn the Japanese culture, including the language. Sundays were devoted to religious observance and community social activities.

Churches serving Japanese immigrants and their families were an important part of community building. Reverend Jingoro Kokubun founded Christian churches in Calexico and El Centro in 1920. He was from Fukushima and had been ordained in Japan but immigrated in 1908, spending several years in Iowa as a student. The he made his way to San Pedro, where there was a significant Japanese population, a few years later. By 1917, he married Iso Kokshun and served as a minister in San Bernardino before coming to Calexico with their two children.

Mrs. Kokubun had been also been an educator, and together they ministered to Japanese families all over the valley. That included leading worship in Calexico on Sunday mornings followed by driving to Union Church in El Centro for services mid day. Two more children were born in the mid-20’s, filling the small home they had next to Independent Church.

In El Centro, the Buddhist Church and Union Church were both on Commercial Avenue , part of a Japantown that ran from 4th to 6th Streets between Broadway and Commercial. Brawley also had a Buddhist Church in the 1920’s and 30’s, served for a time by Reverend Tainen Hirota.

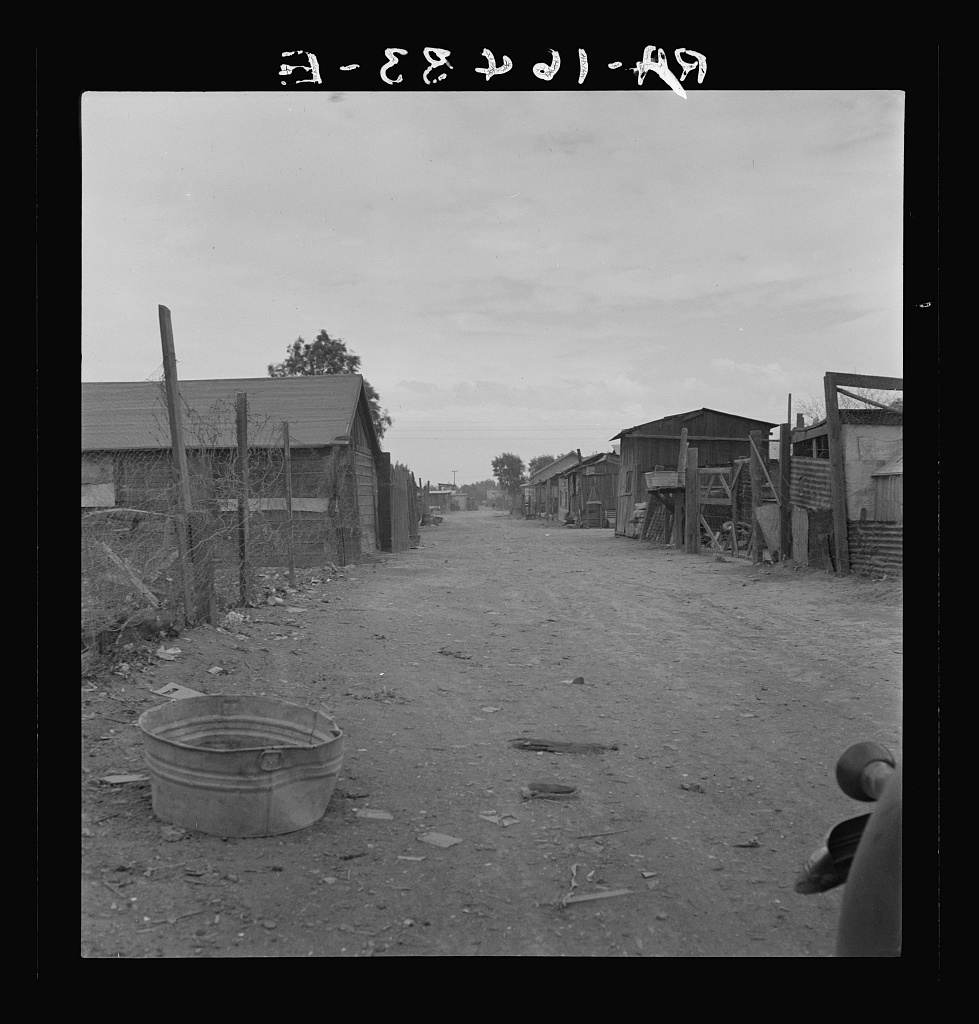

Half of California’s farms were under 50 acres, a quarter under 20. Farms operated by Japanese were almost always on rented land and centered around seven towns of Imperial Valley. El Centro and Brawley had the largest Japanese business districts.

In an interview recorded in 2012, Minoru Tajii described the towns when he was growing up in Imperial County. “There was Brawley, that was the biggest one. And then they had Niland, which is right there by Salton Sea, bottom of the Salton Sea. There you had Imperial, it’s a real small town, and then El Centro. El Centro, Brawley were bigger, then Calexico was small. Then they had a little place called Holtville, that was more towards Yuma way. There was other smaller place like Seeley and things like that, but they’re just maybe one little store or gas pump. Just your Brawley, El Centro and Calexico, Holtville was about the biggest, all the rest are too small.”

Tajii knew most of them intimately, because his family is listed in records as having lived in or near six of them, including Heber and Westmoreland. Minoru’s father had come from Hiroshima to the United States in 1914 while in his late teens. He went back five years later to marry a woman from his home prefecture and they returned on a Japanese ship.

Finding A Way

Minoru, born in 1924, was the second of four children. Among his lasting memories from his childhood are the early methods of housekeeping, including an ice box. “The ice man used to come around once or twice a week,” he recalled, “and you buy a 25-pound cube of ice, and you put it in the top to get the cold air to come down. You never open the top where the ice is, cause the ice would melt too fast…we just cook enough so that they had one or two pieces (of chicken) for the kids to take to school, and keep it cool in the ice box.”

Water for drinking and cooking also required special care. It came from the Colorado River via canals and irrigation ditches, with silt carried along making it tan. So rural families like Tajii’s had to be careful. “We had what they called a sand filter, and then you put the water in a bucket, and then you have a tube that came out from the sandstone, and you have a bucket at the bottom. You suck on the pipe to get the water coming, and then you put that down in the bucket and that’s your drinking water, cooking water.”

There was a special brush used to clean the sandstone, which had to be cleaned and rinsed out about once a week. The family had two mules for plowing, a dog and chickens, and for the animal’s water they’d tap into the irrigation ditch and store muddy water in a pond so the silt would settle to the bottom.

Tajii and his brothers had ready snacks in the fields. If they got hungry, they could go pick a cantaloupe or dig into a watermelon. He observed that they preferred to eat the heart of the melon, and take the rest back to the house, because no farm family could waste food during the Depression.

The Depression

In the 1930 U.S. Census, Jitsuo Tajii is listed as a farm foreman, and the households nearby were headed by men from Tennessee, Nebraska, Mexico and Japan. Sadly, there were only three Tajii children by then. Their three-year-old daughter had died when she tried to cross a canal by herself using a narrow plank, fell off and drowned.

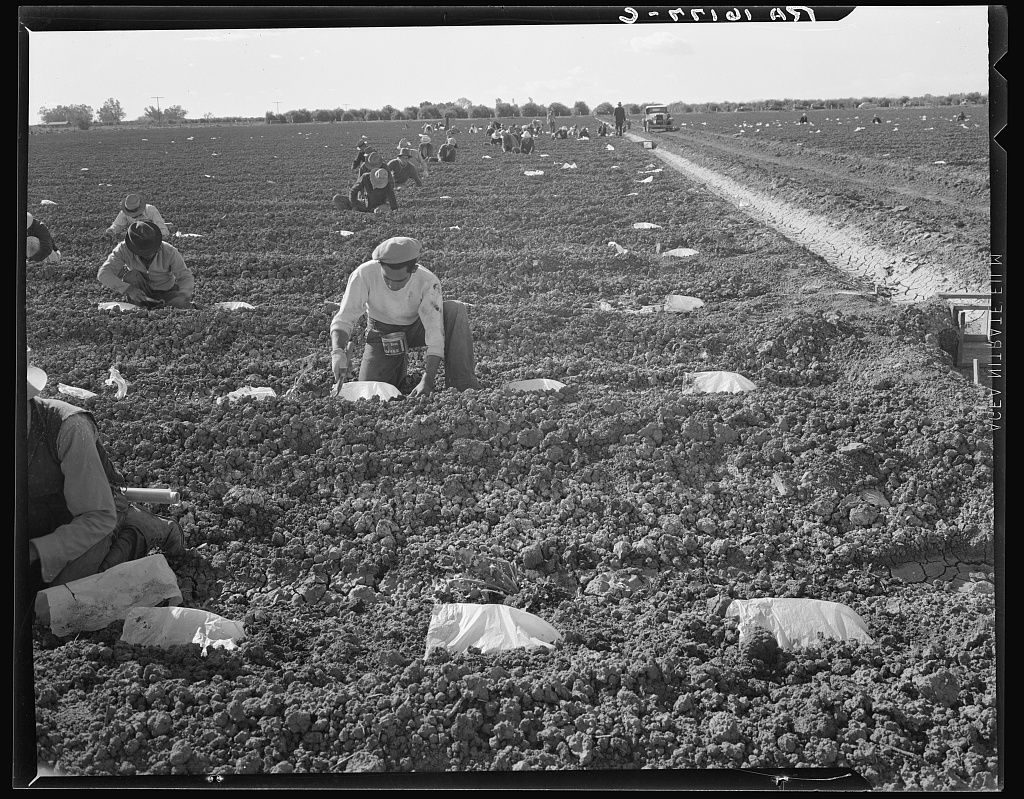

First generation Issei farmers formed a company, the Imperial Valley Growers Association, to better look out for their interests. Gorge Kawanami and son Ken from the Mount Signal Produce Company built a brand for their melons, but that was unusual. Some farmers were sharecroppers, getting one third of the proceeds at the end of the season. Distribution companies were owned by Caucasians, which meant they controlled how much Japanese farmers received for their crops.

The 1930’s were in some ways the peak of the Japanese community in El Centro and its surrounding towns and fields. But it was also a time of change, because the Depression caused an influx of destitute refugees from the Dust Bowl, including would be laborers from Oklahoma, Texas and Arizona. Mexicans had been “guest” workers for a decade, but the influx to the Imperial Valley from south of the border increased in the 1930’s.

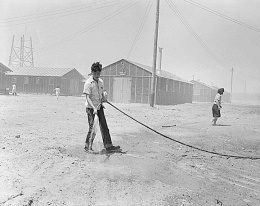

The hardships were inhuman. Pay dropped for field hands, working and living conditions were deplorable. It was an advantage for those who owned or rented land, as their costs for planting and harvesting dropped. But desperate people were earning less than it cost to live in some cases, and the government struggled to provide relief.

From 1930 to the end of the decade, unions tried to organize workers in the Imperial Valley. In writing about labor organizing among Japanese immigrant communities in California, Yushi Yamazaki describes the demands that included “a minimum wage of fifty cents an hour; a fifteen-minute rest period after every two hours of work; abolition of child labor, equal pay for equal work; free ice to be furnished by growers; better housing; better water; and no racial segregation.”

Labor unrest went on year after year. Strikes were broken up by the county sheriff and his officers. Some of the union organizers were jailed, some of the Japanese immigrants involved with strikes were deported. Vigilantes also suppressed organizing, including Associated Farmers, funded by a group of growers in Imperial Valley. Things got to the point where the Mexican government got involved.

The California legislature in 1931 passed the Alien Labor Act, which forbid any business holding a contract with the state to employ aliens in public works projects. In the end, the owners busted the unions, some of whom were accused of being Communist fronts, which Yamasaki confirms in part.

Nine Communist organizers were sentenced from six to forty-two years in state prisons for violating the Criminal Syndacalism Act which made it illegal for individuals or groups to advocate radical political and economic changes by criminal or violent means.

With the appearance of this militant labor movement led by Communists, white-supremacist vigilante groups became increasingly aggressive in California. These included the Associated Farmers, a powerful right-wing group of growers in the Imperial Valley such as Brawley and El Centro, the Silver Shirts in San Diego and a revived Ku Klux Klan in the Central Valley.

First Of The Season

There was a race with mother nature to grow the first produce to market. Because of the desert climate, Imperial Valley farmers had an early growing season. The growers used several techniques to protect seedlings, including covering them when temperatures got into the 30’s.

The Tajii’s work force had become Mexican, and Minoru described an interesting dynamic his parents used for setting the pace of weeding crops with a short handled hoe. “You bend over all day cutting the weeds,” he observed. “because you don’t want to be hurting the plants that you got growing, otherwise you’ll cut the cantaloupe. That was backbreaking work. My mother and father used to go out there and hand (weed), You don’t go slow, you have to lead the Mexicans. So my father would be in the front and my mother would be in the back, and they got to stay in between there and keep up, and all these Mexicans got to work that way. That a very back breaking job, when you’re bent over. Now, it’s against the law.”

When not working, the farm families lived simple lives. Electricity hadn’t come to rural parts of the area until the 1930’s. Leisure time was in short supply, as there were chores to do every day of the week. Weekends offered the best opportunity to be in community with others.

The Japanese Christian Church was complemented by Buddhist Churches in El Centro and Calexico, which had Saturday instruction in Japanese for children whose parents worried that they were losing the language. Similar classes were taught in several other nearby towns.

Public schools were segregated in the major towns, but the only group forced to attend segregated and inferior facilities was the African Americans. Unlike a number of cities in California, there was no separation out of Asian American students in Imperial County.

A Sudden Change

With the Nazis waging war in Europe, and tensions with Japan rising, the U.S. began building its armed forces, including registration for the draft. George Uchimiya continued his education after high school, attending junior college in Brawley. He was drafted into the Army in October of 1941 and started basic training at Camp Roberts near Paso Robles. Then Japan attacked Hawaii, and Uchimiya was transferred to Fort McClelland in Alabama, where a half million troops would be trained during World War II.

Pearl Harbor’s impact on the Japanese community in the Imperial Valley was delayed by a day, because December 7th was a Sunday. The news was unsettling. No one knew what was ahead.

But on Monday, when Minoru Tajii went to class, things were dangerously different.

“We went to school, and hey ‘You’re A J-A-P,’ “he recalled. “They started pushing us around. Oh, yes, because, well, we were Orientals, and you don’t have many Orientals there. And they were all farmers’ kids and we were told not to fight, that they were White, so they’re gonna take it out on the parents. So we were told not to do anything. So we were very quiet.”

A round up of Japanese men had begun on December 8th as well, and continued over the next few weeks and months. Tim Asamen has counted more than one hundred men from Imperial Valley taken into custody during the uncertain time of late 1941 and early 1942. That tally includes his father Zentaro, who was picked up as part of a mass raid on February 19, 1942, the day President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 1066. The order set in motion removal of all those deemed a threat to commit espionage and sabotage in time of war.

Another of those detained was Minoru’s father, Jitsuo. “He was farming out in the field and the FBI came and told him ‘You’re Tajii?’ He said yes. They just handcuffed him and took him away. And we didn’t know where he was for three days. He had no change of clothes or nothing. They just took him out there with the dirty farming clothes.”

Minoru thought his father was removed to Tuna Canyon Detention Center north of Los Angeles because he had been on the board of a local growers association. After initial interrogation, the Japanese prisoners were transported to federal holding facilities as far away as North Dakota.

Closed To Aliens

While the government tried to decide how the evacuation of more than 120,000 residents could be done logistically, families jettisoned possessions they thought might link them to the Japanese nation, including treasured keepsakes and items like radios and guns, which had been confiscated in earlier raids.

The March 3, 1942 headline on the front page of the Imperial Valley Press revealed further restrictions: I.V.Included In Vast Area Closed To Aliens. The United Press article underneath it affirmed forced removal was near:

“The Army today declared the western half of Washington, Oregon and California and the southern half of Arizona a military area from which enemy alien and American born Japanese will be ousted progressively to rid the Pacific coast of a potential fifth column threat.”

The story noted that Imperial Valley was included in the prohibited area. The next day’s Press carried a piece that seemed to back up the threat posed by members of the Japanese community. The headline was: El Centro Spy Operations Told. The article itself relied on comments made the day before in Los Angeles. They were attributed to Kilsoo Haan, a member of the Sino-Korean League, who claimed Japanese agents in El Centro had possessed a timetable for Tokyo’s war plans in advance of Pearl Harbor.

Haan, raised in Hawaii, had been speaking frequently in the western U.S., urging expulsion of Japanese and Japanese Americans. He garnered a good deal of media coverage, but his claims were generally discounted by federal and state officials.

The U.S. Department of Defense, wanting inland aviation facilities in case fields on the coast were attacked, acquired the Imperial County Airport to use as a Marine Corps air station. With 350 days a year of good flying weather, the two runways and weapon ranges were an asset in ramping up defenses.

Ordered Out

On March 29, 1942, the Army general in charge of carrying out the executive order issued a proclamation for forced removal of all Japanese and Japanese Americans in the restricted zones. They were given little time to prepare for departure.

Those facing incarceration sold their business and household goods as best they could, sometimes for pennies on the dollar. Some belongings were stored in churches, temples, and garages. Where leases were in place, arrangements for overseeing the farms were made with neighbors or friends.

Imperial Valley’s Japanese and Japanese American residents were ordered to report to two churches so they could go by bus directly to the Colorado River Relocation Center near Parker, Arizona. It was located on two adjacent reservations, and commonly called Poston, after an Arizona pioneer from the area.

“We lost everything,” remembered Minoru Tajii. “Everybody that had furniture and anything else, you lost everything. Especially your clothes and like that, the only thing we had is the one suitcase.”

Some of his family’s possessions were stored in an airplane hanger. A year after going into Poston, a notice was sent from the hanger’s owner that they had to get everything out of storage. They had no way to do that, except they had kept possession of their car’s pink slip. It was sold for $200, far below value.

Moving To A Reservation

Just over 1,500 adults and children registered at the Union Church in El Centro and the Japanese Methodist Episcopal Church in Brawley. Now in custody, they were driven to the partially completed barracks, some of which had been built by the Del Webb company, later famous for its retirement developments. In fact, the majority of those incarcerated at Poston did not first go to an assembly center before going to the more permanent camps.

A national remote broadcast from Poston was arranged by CBS Radio, with Chet Huntley interviewing one of the initial arrivers, Florence Mori, in late May. Huntley would later become famous for the Huntley-Brinkley Report on NBC TV. Poston had its own newspaper, starting with Poston Information Bulletin, first published May 13, 1942. A second paper had a short run and then the Poston Chronicle with a staff of Japanese Americans, was published from Christmas, 1942 to October of 1945.

Stuff It With Hay

Minoru Tajii’s first impression was bleak. “There’s nothing there. It’s wide open, and when we went into the barracks they told you was going to be your home, there’s gaps in between the wood, the floor has gaps, and when the wind blew, all the dust came in. So it was terrible. We just didn’t like the place.” Adding to his dismay was being directed to pick up a bag and stuff it with hay. It would be his bed, initially in Unit 5-B, Block 59.

Another of the early arrivers was George Fujii, who was asked to help those coming in by bus to get oriented to new surroundings. He was a Kibei, whose family had returned to Japan from 1924 to 1934, his teen years. He was at the University of Southern California when the war started, majoring in international trade, and had witnessed the evacuation of Terminal Island within 48 hours of Pearl Harbor. While in college, he had speculated on land in the Imperial Valley and owned 200 acres there.

Fujii would jump on the buses as they arrived and explain what the process was for those moving in. No more than five family members per room and other requirements. He also gave some help tips, like taking salt tablets daily. He especially dealt with the Issei, as his decade in Japan had given him good language skills.

No Respect

The elders bridled at being ordered around by the government managers. They felt disrespected, and were dismayed to be eating such a strange diet, which was initially made up of mostly surplus items like wieners, sauerkraut and cereal. Fresh milk came all the way from Los Angeles. Apparently the OIA managers planned to have the evacuated farmers do for the barren reservation lands what they’d done for Imperial Valley—turn it into a self sufficient bounty of fruits and vegetables.

While the government spent a lot of money on infrastructure, including bringing in water from the nearby Colorado River, the vision of a permanent agriculture enterprise wasn’t realized. Chickens and hogs were kept, along with flowers and vegetables. Even growing plants to produce rubber was tried.

Feeling he’d been put in a bad position as a go-between, Fujii soon quit his job as an interpreter. Tensions continued to rise as more and more Issei and Nisei arrived in the summer, most of them from southern California. Big city families were mixed in with those who had been farming inland. There were language barriers as well.

Some Distinctions

Poston didn’t have guard towers, the thinking being it was so remote few would try to break out. The closest town was 16 miles away. It was also different in that there were three sets of barracks and support buildings, spaced by a mile or more from each other. The population at its peak in the fall of 1942 was more than 17,000, the second biggest after Tule Lake. The northern-most barracks were twice as big as the other two. Poston was the third largest “city” in Arizona, with no one knowing whether it would be a permanent residence or not.

Another contrast to other facilities was that Poston was overseen by the Office of Indian Affairs initially. There were a number of problems with the OIA administration of Poston, based on both agency philosophy and operational capacity. The War Relocation Authority decided it needed to step in to share oversight almost immediately, and then take over complete control in August, 1943 of what some dubbed the reservation within a reservation.

There had been attempts on the part of OIA staff to foster participation in some of the decisions about how the camp would operate. But a requirement that only Japanese Americans could run for elected council representation did not sit well with the first generation, who were largely not eligible for citizenship. Accusations that the advisory members had become tools of the administration widened the generation gap. It came as social cohesion crumbled with teens and young adults much freer to spend time with their friends, including at meals, sports and social events.

Poston did have an industry of a sort. A camouflage net factory, to aid the war effort, was to start up shortly after the camp was fully populated. Material to weave the nets arrived in October, 1942, but potential workers balked at the proposed $16 a month wage. Something close to outside pay for the same kind of work was desired. Negotiations dragged on, not helped by a labor shortage since so many had left for jobs on the outside. Finally the wage issue was resolved with creation of a reserve fund, and a routine was in place by the end of February, 1943. At its peak, 500 residents worked making nets, but the factory didn’t last much more than a year.

Resistance Behind Barbed Wire

The problems with the camouflage initiative were just one element of the strife at Poston in the fall of 1942. In mid-November, things came to a head after the beating of a man some considered to be a lackey of the camp’s managers. Kay Nishimura, who had suffered numerous cuts and bruises requiring stitches from multiple attackers, had ties to the Imperial Valley. He had gone to El Centro to become a rice farmer in 1940 and had been the executive secretary of the Imperial County Citizens Welfare Committee. Nishimura had reportedly been a translator for the Immigration and Naturalization Service staff in El Centro, and possibly the FBI.

Fifty men were apprehended by camp police, and two of them, Isamu Uchida and George Fujii, became the prime suspects with the possibility of being tried in the Arizona court system. Both were leaders of the Poston Judo Club, which had many members and a reputation that they were not to be messed with.

Efforts by supporters to get the pair released back into the general population initially failed and in protest the elected community council of Japanese Americans resigned. So did members of an advisory group composed of first generation Issei. A general strike followed while negotiations dragged on. After more than a week of unrest, Uchida was released and then Fujii, no formal charges having ever been filed.

Fujii was asked in an interview many years later about the causes of the strike.

“People had strong doubts toward society and government and the administration,” he responded. “And they lost a sense of judgement and got carried by emotion.”

The Poston strike certainly damaged trust—both between the camp managers and those being held solely because of their race, but also among the pioneer immigrants and those who had been born in America. Relations normalized somewhat after the strike, but the facility’s population was diminishing, a trend that would continue to accelerate.

Further Displacement

Leaving imprisonment for higher education or jobs to aid the war effort started almost as soon as Poston opened. Requests were made for men to harvest sugar beets in May, 1942 and that continued for other crops through the summer. Later, if you could get into a college or a trade school, permission would be granted to travel to the new opportunity.

Men of military service age could volunteer to enlist, and after a loyalty survey was given in early 1943, recruitment of volunteers for an all Japanese American fighting unit was commenced. Another choice, for those with Japanese language skills, was to join the Army’s Military Intelligence Service and train for assignment to the Pacific Theater.

In January, 1944 the government instituted a draft of Japanese Americans held in the 10 camps, with 107 eligible men refusing to comply at Poston. It was among the highest number of all the camps.

George Fujii felt the draft was wrong. He put it in writing, opining in postings at Poston and letters to government officials including President Roosevelt and Governor Earl Warren. In one of the missives he wrote that if a young man “were drafted without being recognized as a citizen and then were to die, you would have died in vain.” That got the attention of authorities, and he was jailed for his views. Faced with a trial on sedition charges, Fujii took his chances with an Arizona jury. He was acquitted.

At some point in his time at Poston, Fujii had been approached by a real estate broker about selling his land in Imperial County. He had given up on the idea of rice farming, and after commissions reported he made about $800 profit on the deal. Selling out made sense, given the anti-Japanese environment in the state, especially rural areas.

Starting Over

At the end of 1944, the U.S. government declared the period of military necessity for the removal of Japanese Americans from west coast areas to be over. Governor Earl Warren stated Japanese and Japanese Americans in California would have “the full recognition of their constitutional and statutory rights.”

Some political leaders of Imperial County did not agree. Nor did a number of leaders of agricultural enterprises in the region. A rally was held in December, 1944, in Brawley. It featured John Lechner, who had made news up and down the state for his anti-Japanese rhetoric. Lechner’s message was that return of Japanese to the area would be disastrous and cause civil discord. Also speaking in opposition were Brawley Mayor Elmer Sears and Imperial County Supervisor B.M. Graham.

Beyond racial hate, economics played a role. The Japanese farmers had been gifted at growing produce that was desired in markets across the west and beyond. Caucasian farmers may not have wanted competition after the boom years of the war, when prices were high because of the war effort. They also did not want field workers to be organized. In fact, there was a new supply of hands because of the Braceros program, which allowed Mexican workers to more easily enter the U.S. It was such a popular program with the agriculture industry that the government extended it several times in the later 1940’s and again in the 50’s.

In 1945, eight bills were introduced in the California legislature to prohibit Japanese American land ownership. In the summer of 1945, the legislature placed Proposition 15 on the 1946 ballot to enshrine the existing Alien Land Law in the state constitution. Approval was advocated by the California Chamber of Commerce, Native Sons of the Golden West, Native Daughters of the Golden West, California Grange and the California Farm Bureau.

Opposition was led by the Japanese American Citizens League and ACLU. The measure lost in the November election by 300,000 votes out of a total of about 1.9 million. Real estate covenants denying ownership to Japanese and other Asians lasted until 1948. The state’s Alien Land Law wasn’t repealed until 1956.

Decimation of Imperial Valley’s Japanese Community

The Pioneer Museum’s Japanese American Gallery coordinator Tim Asamen estimates only 200 Japanese and Japanese Americans returned to Imperial Valley after the war. The Buddhist Church in El Centro was sold in 1947 and now houses a Sikh Temple. Brawley’s Buddhist community faded away, as well. The Japanese Methodist Episcopal Church in Brawley also became defunct. Its last resident minister had been Susumu Kuwaro, who served the congregation from 1932 to 1942.

The children of those who did come back most often sought higher education and jobs in California’s coastal communities. A number who were born in the Imperial Valley achieved great success after they left it. Among them were Wakako Yamauchi, Yoshihiro Uchida and George Taniguchi.

Yamaguchi was born in Westmoreland, and spent her early years on a farm. She left Poston after 18 months and went to Utah and then Chicago, where she continued an interest in writing. She returned to California to write short stories and plays, including several set in the Imperial Valley before and during World War II.

Uchida was born in Calexico, and became an accomplished judo competitor. He attended San Jose State before being drafted into the Army, where he was a medical technician while most of his family was in camp. He returned to complete his degree and was the head judo coach at the college for more than seven decades, also coaching in the Olympics. Uchida died earlier this year at 104 years of age.

Taniguchi was born in El Centro and raised in Mount Signal and was a teen while incarcerated at Poston. He served in the military, then pursued a career in Hollywood. While seeking a role in Go For Broke he was introduced to horse racing, and as a jockey in the 1950’s and 60’s won 1,597 races. Taniguchi kept a photo of the finish of all of them, and they are part of his archives, along with his racing gear, at the Japanese American National Museum. He passed away in 2021.

Tim Asamen describes for AsAmNews what he witnessed as a third generation Japanese American. “When I was growing up as a Sansei in the 1970’s and 80’s, there were maybe 15-20 ethnic Japanese families spread out throughout the county (around 100 individuals). there was a JACL chapter and a Japanese women’s club that jointly organized an annual Christmas party and in the spring a Keirokai banquet held in honor of the few remaining Issei. That was the extent of a sense of ‘Japanese American community.’ Neither organization exists today.”

Asamen believes there are ten residents of the Imperial Valley who trace their ancestry back to families who lived in the region before Pearl Harbor. He adds that there are a handful of other Japanese Americans who have moved there for work opportunities.

Not Forgotten

In the 2020 decennial census, 1.5% of the El Centro’s population of about 44,000 is of Asian heritage. Of the handful of restaurants serving Japanese cuisine in the city, one has a Japanese sushi chef.

But the valley’s Japanese heritage is recognized, both by those who live locally, and others who travel out of respect for the pioneers and the lives they lived in the 20th century.

The summertime rides that Imperial Valley Japanese families used to take in the 1920’s and 30’s to escape the valley’s incredible heat are now reversed by San Diego community members coming to honor the Issei and Nisei.

Continuing a tradition that goes back more than six decades, members of the Buddhist Temple of San Diego travel east to conduct cemetery services. They not only visit the Buddhist graves, but stop at some of the Japanese Christian sites as well—Brawley, El Centro, and Calexico among them. The Japanese graves are in the older parts of the plots, but not forgotten by those meditating in gratitude.

Most of the sojourners from the coast, including some from Los Angeles, also want to see Japanese American Gallery at Pioneers’ Museum in Imperial. It’s one of 15 exhibitions on the various ethnic groups that are part of the Imperial Valley’s history. The museum is open Tuesday through Saturday, 10-4, and Sunday noon to 5 p.m.

AsAmNews is published by the non-profit, Asian American Media Inc.

We are supported through donations and such charitable organizations as the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. All donations are tax deductible and can be made here.

Please follow us on Instagram, TikTok, Facebook, YouTube and X.

I currently live in Central Coastal CA

From an adapted Poston FAR; Mixed Marriages:

1. Benjamin & Thelma Cornejo entered from Brawley 5/2/42, exited 9/3/42 to Cupertino CA. [Benjamin and Thelma names used in Luis Valdez’s “Valley of the Heat” … ca 1914]

2. G.S. and Haru Dequin entered from San Juan Bta 7/1/42, exited 9/8/42 to Gilroy CA

My info says this was done “on the fly” and interesting ‘variations’. Notably NO children NO exit allowed. Another related ‘variation’ noted.

The above 2 of @30 to/from Poston. I believe to/from 10 camps XXX+