By Amy Xiaoshi-DePaola

Linda Yip’s journey into genealogy began with uncovering a small yellow card in her father’s desk.

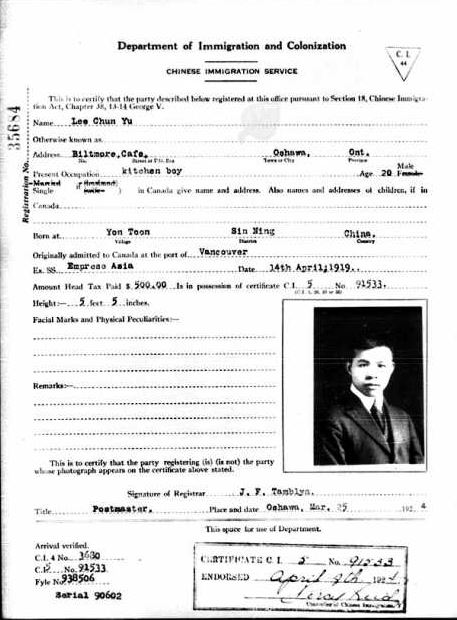

Yip’s father had been issued it at two years old in 1924, a reminder that the Canadian government took away his citizenship status during the country’s Chinese Exclusion Act. He carried the document with him until his death in 1989.

Yip’s family came from the rocky and arid area of Duhu (杜侯) in Shen Tang (聖堂) village, eight kilometers from the Chinese coast. Surrounded by farmers and fishermen, it was a constant struggle to survive, so Yip’s great-grandfather emigrated first to California in about 1870, then settled in Canada in 1880.

Though Yip’s ancestors were never able to share their struggles with their children, their stories continue to resonate. Yip, in particular, is moved by her father’s experience:

LATEST STORIES

“He was the one who paid the price for exclusion, and I was the one to reap the benefits.”

Yip can trace her lineage back twenty-four generations, and she hopes others can start to find their own stories through Ancestry’s free release of more than half a million digitized records from the Chinese Exclusion Act era in North America.

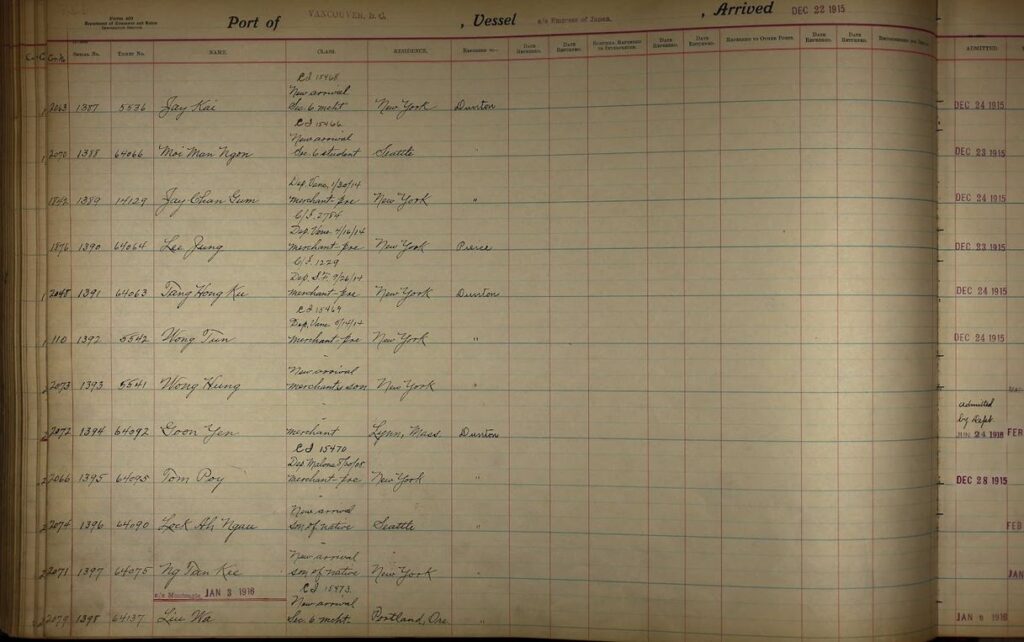

Among the records are photographs and other documents specific to North American Chinese history—including U.S. border crossing records and immigration case file indices, as well as the 1923 Canadian registry of Chinese residents—that can help detail what family members experienced; in particular, the Canadian registry has photos of over 60,000 people.

“We are very excited that Ancestry has made these Exclusion-era records available to the public,” said David Uy, the executive director of the Chinese American Museum in Washington DC to AsAmNews by email. “It is a significant piece to a larger effort to give attention to a largely underserved if not forgotten part of American history. For many doing genealogical research, this has been a missing swatch of information, once thought to be inaccessible.”

Ancestry approached Yip for the project—a timely moment, she said, as it marked exactly 100 years after Canada’s Chinese Exclusion Act, as well as the openings of Northern American Chinese museums in D.C. and Vancouver.

“It was a perfect opportunity for Ancestry to look at its collections and say, ‘What can we do to help further Chinese persons for finding our stories?’” Yip said in a phone interview. “It was a win-win for me.”

But the road to uncovering these individuals wasn’t as simple as entering a name and date.

Yip explained that for Chinese people, there are record gaps, particularly for photographs. Descendants can build on Ancestry’s free collection for their own research and for more details on specific family members.

“Chinese genealogy relies on finding that first document, then analyzing it for the next clue, be it census, city directory, or passenger list,” Yip explained. “Newspapers are a great resource, but historians might not find their ancestor mentioned by name but rather by a racially-pejorative term.”

For instance, Yip explained, if a White person’s store was robbed, a newspaper headline might read “Johnson’s store robbed,” while if the same event happened to a Chinese person, it would say “Chinaman’s store robbed.”

Yip also said that the method of “cluster research”—or finding a person in conjunction with other details such as family members, age, gender, images, location, occupation and time they were living in the area—was essential.

Still, her search through digitized records was an easier journey than when she first started researching Chinese gemology.

“There was nothing,” Yip said. She recalls interviewing family members and searching for mentions of any Chinese Canadians in the library, even purchasing texts from used bookstores and creating her own scholarship.

Ancestry has also released free records of underrepresented communities prior, including the eras of slavery, Reconstruction, the Holocaust and Japanese Americans during World War II. But the Chinese Exclusion Act is another key piece in history.

More than 100,000 Chinese immigrants were living in the U.S. at the end of the 19th century. Lynchings targeting the Chinese community were common, the most brutal involving the massacre of 10% of the Los Angeles Chinese community. Chinese laborers were scapegoated for declining wages, as they accepted lower pay for working in the gold mines, the Transcontinental Railroad project and more. Proposals for anti-Chinese legislation swelled in Congress, with “purely racist” arguments accusing immigrants as lazy, dirty, immoral and unassimilable, as detailed in Lisa See’s family memoir On Gold Mountain.

In the U.S., President Chester A. Arthur signed the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882, preventing the immigration of Chinese laborers. The Geary Act later threatened those who lived in the U.S. unlawfully with imprisonment for up to one year, deportation and denial of bail; as a result, not a single Chinese person entered the country in 1892. Canada passed its own version, the Chinese Immigration Act, in 1923; it forced all Chinese residents in Canada to register with the government. The natural-born, who had no prior certificates, carried the documents as proof of their status. Canada’s Chinese Exclusion Act was repealed in 1947.

In the U.S., the Chinese Exclusion Act remains the first and only federal law that barred a specific nationality from becoming citizens, as well as the catalyst of more immigration restriction laws. It remained in place until 1943 when China became an ally in World War Two. In Canada, the Chinese Exclusion Act was also the first and only federal law aimed at preventing a specific racial group from immigrating and naturalizing; the first federal law to target a specific racial group was the Indian Act.

Though lawmakers from both the U.S. and Canada have apologized, the impacts remain in both countries. Not only were families separated for decades and suffered the loss of roots and identity, Yip said, the pressure of having to prove themselves as American or Canadian citizens continues to ripple throughout generations.

“We sacrifice family connection for economics, and then we do everything to uphold what we see as success factors,” including higher education and prestigious careers, Yip said. Yet, despite contributing to the economy, their accomplishments are used against the community to this day.

Yip pointed to the rise of anti-Asian hate during the COVID-19 pandemic and the current debate on whether there are “too many” people of color in prestigious universities.

“Racism is a virus that never goes away. We like to say, ‘It was a long time ago’ … but that’s not true,” she said. “Our legacy is to inform ourselves, so we can tell the stories our parents couldn’t.”

Yip’s father’s C.I.45 card is currently on display in the Chinese Canadian Museum. She remembers sitting outside during the opening ceremony, dragon dance music playing, and beginning to cry.

“I had a full circle moment of ‘Holy cow, this is my story,’” Yip recalled. “Now, my story helps inform people to find their story.”

Ancestry is doing a deeper dive following the release of the Chinese Exclusion Act era records. The corporation will host a free virtual panel discussion on July 18 at the Chinese American Museum in Washington, D.C. Ancestry also had a Facebook Live event on July 11 with genealogists Crista Cowan and Yip.

“Our free online conversation on Tuesday, July 18, 2023, 6pm ET will not only touch on the new opportunities the Ancestry data provides, but also interesting parallels between Chinese exclusion in both the US and Canada,” said Uy of the Chinese American Museum. “I am fortunate to be joined by Mae Ngai, Lung Family Professor of Asian American Studies and Professor of History at Columbia University; Linda Yip, an author, researcher, and expert in Chinese Canadian genealogy; and Ted Gong, Executive Director, 1882 Foundation.”

You can browse and search in the Ancestry collections here at no cost, along with Yip’s tips to get started on uncovering family histories.

AsAmNews is published by the non-profit, Asian American Media Inc. Make a tax-deductible donation of at least $40 or pledge a monthly recurring donation of at least $10 by August 31 and receive a free copy of The Legend of Mu Lan: Heroine of Ancient China, the inspiration for the classic Disney movie. We are supported in part by funding provided by the State of California, administered by the California State Library in partnership with the California Department of Social Services and the California Commission on Asian and Pacific Islander American Affairs as part of the Stop the Hate program. To report a hate incident or hate crime and get support, go to CA vs Hate.