By Rachel Phua

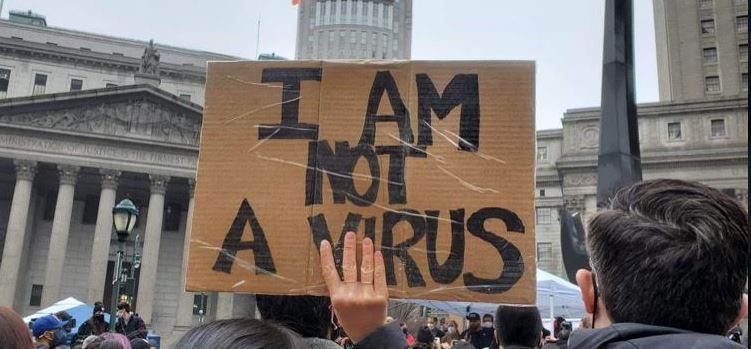

It was exactly 1,195 days since the U.S. declared Covid-19 a national emergency that Amy Cheung got pushed down the stairs at a 5th Avenue subway station where the 7 train stopped in New York City. Between the declaration and the incident, most Americans went into panic mode, and many lashed out at people of Asian descent. Hate crimes against Asians doubled, businesses in Chinatowns across the country suffered, and people were harassed non-stop online and offline.

But this year, life seemed to be going back to normal. The emergency status was taken down, people were walking around maskless, and returning to offices and restaurants. Cheung’s rude awakening came on June 21, 2023, a little past 2 p.m.

“Oh great…you’re in my way,” the 47-year-old Christian ministry worker remembered the words the man in front of her said before he pushed her down the stairs. He had been walking up the stairs while she was with a friend, walking down. Cheung said the entrance was wide and she tried to move out of the way for the man — who she remembered being muscular and around 5 ’10 — but had little time to react. She fell on her back and her hip was bruised.

The man and Cheung exchanged verbal insults, but Cheung, still in shock, couldn’t chase after the man. She didn’t report it to the police because there were no other witnesses in the station, and she did not see any surveillance cameras, she said.

LATEST STORIES

“Right now, I’m feeling a combination of being scared and extra careful and also being very angry,” said Cheung in an interview about 10 days after the incident. She is also “so worried” for her mother- and father-in-law, who take the train to Chinatown every day.

Cheung’s story is one of the many that is still happening three years into the pandemic across the U.S. Just earlier this month in New York City, an Asian woman was beaten and berated in a subway train. In Portland, Oregon, a Japanese diplomat was pushed to the ground by a woman in June. In Las Vegas, a man was left bloodied and bruised after his neighbor attacked him.

This comes even as official statistics show that hate crimes against Asians have fallen since the height of the pandemic. Open data from the New York City Police Department (NYPD) showed that anti-Asian hate crimes fell from 111 in the first half of 2021, to 58 and 23 in the same period in 2022 and 2023 respectively. In California, anti-Asian hate crimes fell to 140 in 2022 from 247 in 2021. And in Los Angeles specifically, hate crimes and incidents are both down so far this year compared to 2022.

The Manhattan District Attorney’s Office in New York is still prosecuting many hate crime cases. As of August 2nd, 2023, there were 131 hate crime cases pending. About a third of them (41), were anti-Asian cases, said Hannah Yu, the hate crimes unit chief.

Anti-Asian hate still high

“Unfortunately, anti-Asian hate crimes, we’re still seeing an all-time high number of cases being prosecuted as hate crimes in Manhattan,” Yu said. She added that a single indictment can contain charges related to multiple incidents. The office can add on a hate crime charge even when it wasn’t initially reported as one by the police if prosecutors discover evidence of racial bias during their investigation.

Data collected by advocacy groups show that the number of hate incidents are more than what officials report. For example, the Asian American Bar Association of New York found 233 anti-Asian incidents in New York City over the first three quarters of 2021, compared to 118 hate crimes the NYPD reported. Dr Elaine Chiu, one of the paper’s co-authors and a law professor at St. John’s University, said they use a combination of official and media sources for their tally, noting that her report’s figures include “potential” hate crimes.

“We were trying to sit in the perspective of just an ordinary community member. Because in our community, people were getting incredibly frightened,” Chiu said. “They weren’t just learning about these incidents from the official report to the police, they were learning about them from the media. And so any incident that a journalist would write is a possible hate crime that made them scared.”

The NYPD did not respond to requests for comments.

Nationally, figures from groups like Stop AAPI Hate and Committee of 100 were higher than what the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) reported too. Stop AAPI Hate reported about 11,500 acts of hate between March 2020 and 2022. A joint report by Columbia University and Committee of 100 found that about three out of 10 of nearly 6,500 Chinese Americans it surveyed in 2022 were verbally or physically harassed.

Meanwhile, the FBI’s data showed a total of 1,025 anti-Asian hate crimes in 2020 and 2021. \

Why not every incident is a crime

Granted, not every hate incident is a crime. As Stop AAPI wrote, most hate incidents are non-criminal, such as the use of racial slurs, which is generally protected under the First Amendment.

Shuai Hao was riding a train in August in Brooklyn, New York, when he got stabbed in the neck and near his eye by a homeless man.

Fortunately, the attack was not life-threatening. Once others in the carriage saw he was getting attacked, they quickly intervened and fended the man off. The man got off the train and was arrested after the police subdued him, Hao said.

Hao said the crime was not considered a hate crime by the police because the man did not have a record of making xenophobic comments, nor did he use any racial slurs during the attack. The case is still awaiting trial.

But Hao, who is Chinese, believes the attack was racially charged. He was the only East Asian in the carriage, he said.

“Emotionally it is hard to accept (that it’s not a hate crime), but rationally I know it’s just impossible to categorize it as a hate crime,” Hao said. The 27-year-old software engineer moved out of the city afterward.

“It doesn’t make sense to continue to live in the big cities, especially New York City. I don’t feel safe having my future kids ride the subway,” he said.

Some say they were discouraged from reporting the incident, Committee of 100 noted based on the responses it got. It said those who reported bias and hate incidents to authorities “did not receive any follow-up actions or were discouraged from further pursuing accountability.” Experts have also previously said hate crimes are likely undercounted.

John Eterno, a Molloy University criminal justice professor and former NYPD captain, said police numbers should only be looked at as a kind of gauge, and should be triangulated with data from other sources, including data from advocacy groups and emergency room visits for assaults.

“Sometimes it’s a lack of trust in the police (why crime is underreported), particularly in minority communities” Eterno, who recently co-edited the book How Countries Count Crime: An Exercise in Police Discretion, said. “Or the police may actually willfully not take a report. That can be for a number of reasons (such as) laziness.”

Eterno co-wrote a paper in 2016 based on an anonymous survey of 1,770 retired NYPD officers. More than four in 10 of the officers said they were personally aware that crime reports were changed to improve crime numbers due to pressure from management to make it seem like crime was falling. Eterno said the police should hire external auditors to look at their data and how cases are processed.

Hard to prosecute

Hate crimes are also known to be tough to prosecute. The FBI says the crime has to be “motivated in whole or in part by an offender’s bias.” In New York State, the bias belief has to be “in whole” or a “substantial part” of the crime. The City reported earlier this year that in New York City, only about 15% of hate crime arrests result in a hate crime conviction, based on data from the city’s five district attorney’s offices. The conviction rate is 23% in Manhattan.

Yu emphasized the need for the motivation to be substantial, “because then, any attack against pretty much anyone would amount to possible hate crime.”

She added that sometimes, even when the prosecutors argue that a case is a hate crime, juries may not. “Unfortunately, the way these incidents happen we’re not going to get…complete admission,” she said. “I think it’s a matter of juries needing really clear evidence of motive.”

The Asian American Bar Association of New York wants the state and city to lower the standards needed to prove a hate crime, partly by changing the phrase “in substantial part” to “in part,” and including all offenses — unless explicitly excluded from the law — as possible acts of hate.

Chris Kwok, a board member of the association, said they are engaging with state lawmakers to introduce a bill to update the law.

No bill has been introduced to change hate crime laws in either legislature. Yu did not comment on the bill. A Manhattan DA’s Office spokesperson said they are “waiting to see the final bill language once it is introduced.”

It is not just an undercount of anti-Asian hate crimes, or difficulty convicting hate crimes. Many Asians don’t feel comfortable stepping forward as well.

Cheung, the woman who was pushed down the subway stairs, said she did not report the incident to the police because there were no witnesses around aside from her friend, and she did not see any surveillance cameras in the station. “It didn’t occur to me that this fits the description of a hate crime,” although she said that if it happened to others, she would think of it as a hate crime.

Taking hate seriously

Culturally, Asians tend to downplay incidents as victims, said Derrick Leon, the executive director of the New York City-based advocacy group Asians Fighting Injustice. “If your parents are immigrants, the way that they survived was to keep quiet, keep their head down and work hard, right?” he said.

Many Asians also think that unless the incident was physical and serious, there is no point reporting because nothing will happen anyway, Leon added. And if they do not speak English and their immigration status is in a “gray area,” they may be even more hesitant to report. To be sure, the NYPD stated it does not ask about immigration status and investigators who can do language translation.

Eterno said the fact that Asians are still afraid of going to the police means they have to do a “far better job” of engaging the community. They also need to hire more Asian officers — the NYPD diversity data showed that while 14.1% of the city’s population is Asian, only 10.6% of officers are Asians.

Though not every ethnic slur is a hate crime, the police should still step in if they overhear the comment, Eterno added.

“Bias incidents need to be taken very seriously… and they should ask you, ‘Is everything okay? Are you all right?,” Eterno said. “They need to make people feel comfortable in public spaces. That’s their job.”

While the pandemic may have subsided, ongoing anti-China rhetoric has caused Asian Americans to feel scared they will continue to be discriminated against.

Yang Chen, the Asian American Bar Association of New York’s executive director, said the ongoing US-China tensions will affect foreign policy rhetoric at the federal level.

“Before Covid came, Trump had already reoriented the US-China relationship. Covid set Trump on fire,” Chen said, adding that while Biden’s rhetoric is not as crude, he has kept Trump’s anti-China policies such as tariffs and restricting the sale of advanced semiconductor chips to China.

Ongoing anti-Asian sentiments have left many Asians in America afraid, even if they have never been physically assaulted for their race.

“I don’t buy the narrative that these people…pick someone random,” Yixi Chen, a doctoral student at Columbia Business School, said in reference to the death of Michelle Go, who was pushed in front of an oncoming train. “Why do they always pick Asian women?.. Every time I’m in the subway I become extra vigilant. My whole body tenses up. I’m still afraid.”

“Covid was just a trigger,” Yixi Chen said, hoping that authorities and members of the public will continue to take anti-Asian incidents seriously. “It’s always been there historically. The pandemic just aggravated and legitimized Asian hate.”

AsAmNews is published by the non-profit, Asian American Media Inc. Follow us on Facebook, X, Instagram, TikTok and YouTube. Please consider making a tax-deductible donation to support our efforts to produce diverse content about the AAPI communities. We are supported in part by funding provided by the State of California, administered by the California State Library in partnership with the California Department of Social Services and the California Commission on Asian and Pacific Islander American Affairs as part of the Stop the Hate program. To report a hate incident or hate crime and get support, go to CA vs Hate.

Vitally important to keep anti-Asian attitudes at the forefront of all instances of intimidation and violence against Asians.

Would be great if Asians had a self defense mentality … but we don’t seem to. First video of anti-Asian hate I saw was of two elderly Chinese males in San Francisco Chinatown, getting beaten, and robbed. That intersection was very crowded but all everyone could do was watch with their mouths open. No calls to stop. No pot banging. No nothing.