By Abe Levine

(This is part of our ongoing series, Lost Kinjo- a look at the more than 40 Japanese communities that disappeared after World War II. It is supported by funding from the California Public Library Civil Liberties Project and the Takahashi Family Foundation.)

When Charles “C.F.” Seabrook faced a wartime labor shortage to power his industrial farm, he turned to incarcerated Japanese Americans. This audio story follows the journey of Tamihei Hashima and his descendants from Brawley, California to Seabrook New Jersey, pulled by opportunity and forced displacement.

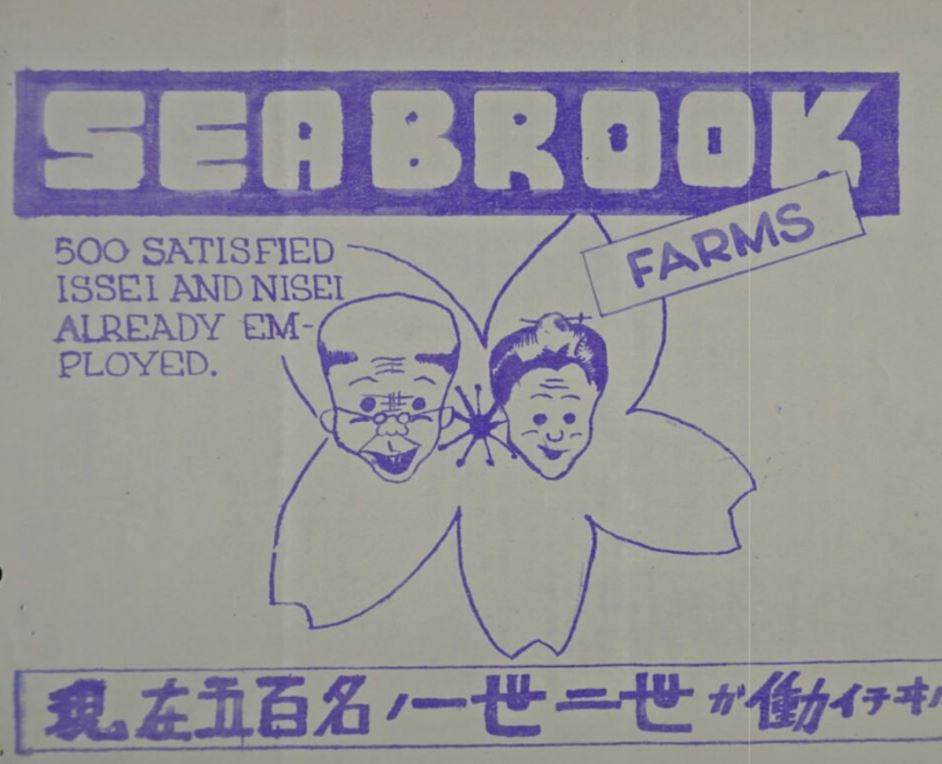

Photo from Seabrook Education and Cultural Center via Rutgers University.

Transcript

Masaru “Mas” Nakawatase: You know it’s interesting how we, In this country, we get all these sort of romantic notions about immigrants and how we built this country, which is true -except when it actually happens, people don’t want em.

Abē Levine: Japanese immigrant farmers made historical impacts on California’s agriculture. They transformed undesirable land into fertile ground and drastically expanded harvests. But, both the local communities where they lived, and the federal government, responded to them with fear and retribution rather than gratitude.

LATEST STORIES

Masaru Nakawatase, or Mas for short, was born in an incarceration camp in Poston, Arizona in 1943. Just a few decades earlier, his grandfather Tamihei Hamashima immigrated to the Imperial Valley in Southern California. Mas says his grandfather arrived…

Mas Nakawatase: Pretty early in the 20th century. I mean, somewhere around 1908

Abē Levine: Hamashima settled in the city of Brawley. He worked alongside other immigrant farmers who leased land from White owners.

Mas Nakawatase: It was a multiethnic area. I mean, you had, besides Mexican Americans, you had a lot of South Asians.

Abē Levine: Hamashima helped found an agricultural association to organize fellow farmers. But being a community leader had consequences.

Mas Nakawatase: After Pearl Harbor, he got picked up by the FBI because he was part of the leadership class.

Abē Levine: On February 19th, 1942, President Roosevelt signed Order 9066, placing all Japanese Americans living on the west coast into incarceration camps.

Mas Nakawatase: Somebody was keeping tabs, because he got picked up right away, within a few days of the bombing of Pearl Harbor.

Abē Levine: Mas’s grandfather was among 48 notable Japanese men detained during an FBI raid of the Imperial Valley.

Mas Nakawatase: He was incarcerated in North Dakota, and he was in North Dakota until I guess this late spring, early summer of 1942.

Abē Levine: Eventually he was reunited with his family, including his daughter Aiko, Mas’s mother. Aiko met Mas’s father, Kenzo while imprisoned behind barbed wire in Poston, Arizona. Though he was only a baby at the time, his parents told him about the living conditions there.

Mas Nakawatase: Poston, Arizona was very hot, and it could get very cold. And the barracks that they lived in were uninsulated.

Abē Levine: After a year in prison simply for being Japanese, Mas’s family relocated to Arkansas. Although there were two incarceration camps there, Mas’s family found work on privately owned land - a 65,000 acre plantation owned by the Wilson family.

Andy Urban: The history of Japanese American incarceration is a labor history, right.

Abē Levine: That’s Rutgers University labor historian Andy Urban.

Andy Urban: The federal government almost immediately thought about how it could redeploy these kind of displaced persons for wartime needs.

Abē Levine: And that’s how Mas’s family, and 2500 others like his, ended up in Southern Jersey in the early 40’s. A major agribusiness called Seabrook Farms in Seabrook, New Jersey took advantage of this newfound labor supply.

ARCHIVAL VIDEO: 1940s New Jersey Travelogue from Periscope Film

New Jersey is called the Garden State. A large share of the frozen foods of the world are grown here on highly mechanized farms. So critical is the time element in processing these crops, that field supervisors are equipped with radio telephones for constant contact with their headquarters. Lima beans that left the ground a few minutes ago are processed in huge machines.

Abē Levine: Seabrook Farms was the world’s largest supplier of frozen vegetables in the 40’s and 50’s, and they had large government contracts to supply military rations.

Mas Nakawatase: The deal was that Seabrook Farms would provide jobs, they would provide housing, and some social services.

Abē Levine: Charles Seabrook (C.F. Seabrook), who founded the company, recruited Japanese Americans from incarceration camps, as well as other displaced populations domestically and overseas.

Andy Urban: In 1943, 44, Seabrook Farms learns about the new availability of incarcerated Japanese American labor and begins partnering with the War Relocation Authority, as well as some other federal agencies that are involved in these programs, to bring them to New Jersey.

Abē Levine: Mas’s mother found work packing vegetables, and his father worked as a mechanic.

Mas Nakawatase: And in the summer, I mean everything was going gangbusters in terms of the crops coming in, you basically had 12-hour shifts. When the adults went down for… because they had been working on the night shift. You didn’t mess with that. You know?

Abē Levine: At its peak in 1947, Seabrook was home to the largest concentration of Japanese Americans in the country.

Mas Nakawatase: You had kids that looked like, sounded like you, ate like you. You know, all of that. We had our own kind of sense of ourselves.

Abē Levine: Japanese Americans in Seabrook formed their own associations, as they had in the Imperial Valley. Cultural celebrations like Obön, a festival to honor ancestral spirits continue on today.

Mas Nakawatase: There were two churches, there was a Buddhist temple and a Christian church. I mean there were boy scouts.

Abē Levine: He says-

Mas Nakawatase: When you grew up in a community like that, I think there was much more security.

Abē Levine: But working and living conditions weren’t ideal for everyone.

Andy Urban: Seabrook Farms is kind of at the forefront of this early attempt to use refugee status to exploit workers and put them in dangerous and precarious jobs.

Abē Levine: Japanese Americans worked alongside European refugees, Caribbean guest workers, and Black migrant laborers from the south.

Andy Urban: And that dynamic, that fear that Seabrook Farms is going to bring in too many Black migrants, is going to establish a permanent Black community in the region, really drives the effort to look into Japanese Americans.

Abe Levine: Japanese employees came in successive waves and under different terms. They had diverging experiences of adversity and exploitation.

Andy Urban: So after the war’s end, more Japanese Americans were coming to Seabrook Farms, and this is where it gets kind of really interesting.

Abē Levine: The mass incarceration campaign transcended national boundaries. Thousands of Japanese Latin Americans were deported and placed in incarceration camps. The majority were taken from Perú.

Andy Urban: In August 1946, roughly 300 Japanese Peruvians are paroled, very specifically paroled to Seabrook Farms. So they have to continually report to the Immigration and Naturalization Service in Philly. You know, they’re essentially kept under, kind of, restricted movement and so forth.

Abē Levine: One formerly interned Japanese Peruvian, Seiichi Higashide, said it was like living in partial confinement rather than total confinement.

Andy Urban: You get another group of roughly 300 individuals known as the Renunciants and Enemy Aliens. Five thousand American citizens of Japanese descent renounce their U. S. citizenship. These individuals then end up in federal prisons. They bounce around. So a lot of them are eventually granted release. But they’re actually in New Jersey subject to what’s called relaxed internment. So even stricter than the Japanese Peruvians, they’re not allowed to leave the company grounds for more than six hours, and they’re not allowed to go more than six miles. They have to report any movement to company officials. And so essentially they’re kind of like a type of prison labor.

Abe Levine: But, For families like Mas’s, staying in southern Jersey, was preferable to returning back west.

Mas Nakawatase: I think there was probably a lot of reluctance about going back west,

a lot of a lot of California is Washingtonians and Oregonians, you know, wanted them the hell out

Abē Levine: County supervisors in Brawley organized a rally urging the governor, the U.S. congress, and the president to keep Japanese families out of the Imperial Valley. Ultimately, Japanese settlers and their descendants were effectively exiled from the Valley. Mas has one message about the displacement of Japanese American communities that reverberates today.

Mas Nakawatase: There’s no Asian that’s more than a generation away, you know, from a camp or a prison or forced migration. And none of these things happened in isolation from one another. The incarceration of Japanese Americans came within an anti-Asian climate that had been nurtured for years.

This project was reported and produced by me, Abē Levine. The music you heard came from Blue Dot Sessions. Archival footage of pastoral New Jersey came from the Internet Archive. This story is part of Lost Kinjo, a series on Japanese American communities displaced due to mass incarceration. It was made possible by funding provided by the California State Library Japanese American Civil Liberties Program and the Takahashi Family Foundation.

AsAmNews is published by the non-profit, Asian American Media Inc. Follow us on Facebook, X, Instagram, TikTok and YouTube. Please consider making a tax-deductible donation to support our efforts to produce diverse content about the AAPI communities. We are supported in part by funding provided by the State of California, administered by the California State Library in partnership with the California Department of Social Services and the California Commission on Asian and Pacific Islander American Affairs as part of the Stop the Hate program. To report a hate incident or hate crime and get support, go to CA vs Hate.