By Raymond Douglas Chong

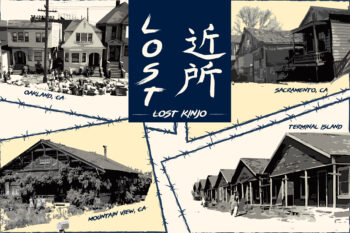

(This is part of our ongoing series, Lost Kinjo- a look at the more than 40 Japanese communities that disappeared after World War II. It is supported by funding from the California Public Library Civil Liberties Project and the Takahashi Family Foundation.)

Until 1942, a tiny Japanese American community thrived in Fowler Japantown, “The Blossom Trail City,” south of Fresno, in the agricultural San Joaquin Valley in California. According to the 1940 federal census, 159 Japanese Americans lived in Fowler.

Fowler Japantown

At the farming center, Fowler Japantown served residents and seasonal laborers. Just south of Fresno, it had Fowler Buddhist Church and a Christian church, two hotels, one restaurant, two Japanese language schools, five stores, three garages and several business associations.

After the incarceration, the Fowler Buddhist Church and a tiny Japantown formed on 4th Street until Honda Garage closed in 2008.

LATEST STORIES

During the diaspora from Imperial Japan, male Issei pioneers arrived from the Port of Yokohama to the Port of San Francisco. They came mainly to labor on the farms across California. The 1900 federal census showed 10,151 Japanese Americans, 9,598 (95%) male, a bachelor society.

After the 1908 Gentlemen’s Agreement between Japan and the United States, picture brides came through Angel Island Immigration Station to marry the Issei pioneers. Picture brides were a Japanese matchmaking practice in which a matchmaker matches the bride and groom using only pictures. The Ladies’ Agreement of 1921 ended the practice of picture brides.

In her Discover Nikkei article – Mukashi Banashi, November 25, 2010, Dr. Akemi Kikumura Yano interviewed several picture brides. During this early “Bachelor Society” period, Nihonmachi catered to a young male, a migratory population. Gambling halls, saloons, and brothels were attractive venues for vices. “Fowler’s Japanese community found thirteen business establishments (nine Japanese and four Chinese) four boarding houses, three pool rooms, three restaurants, and one barber shop,2 the numbers and kinds of establishments reflecting, in part, the character of the population that sustained them.”

Tora Renge recalled her life as a picture bride in Fowler Japantown with Yoshino Hasegawa on February 11, 1980, as part of the Japanese American Oral History Project now housed at the Fresno County Public Library.

Yoshino Hasegawa: How long have you lived in this country, Mrs. Renge?

Tora Renge: Well, I came to the United States in 1917.

Hasegawa: How old were you when you came to America?

Renge: Well, let me see. I know I was very young. Well I was born in 1895, and I came to America in 1917, so I was about 22 years old.

Hasegawa: In what part of Japan were you born?

Renge: I was born in Hiroshima-Ken, Hiroshima-Shi, Kabe-machi, Aza Kami-Machi. Today this is part of Hiroshima City.

Hasegawa: When you first came here, Mrs. Renge, how many Japanese families were there in the area around Fowler?

Renge: There was quite a number. When my husband came to Fowler, there were the beginnings of a Japanese town. All the Japanese lived in the area near the Buddhist Church. The Fowler Do-Shin-Kai was the second or third house from the south corner by the Buddhist Church. I think the members of the Do-Shin-Kai built that hall. I don’t know when they built it, but many activities were held there. Since there were so many people from Hiroshima-Ken, the people from Hiro-ShimaKen started a club. I have a good picture of 30 to 40 people who were members of the Hiroshima Kenjin Kai.

Hasegawa: Was that Do-Shin-Kai changed to Hiro-Shima-Ken-Jin-Kai?

Renge: Later, when most of the single men were married by the picture bride system or otherwise, and many children were born, the organization was changed to Japanese Language School.

Hasegawa: About how many students were there at that time?

Renge: Well, let’s see. There were quite a few. Anyway, my oldest daughter and oldest son went.

Hasegawa: Would there have been 50 or more?

Renge: I think about 50 students, but the number increased.

Hasegawa: Was there a Christian church in Fowler?

Renge: Not a Japanese Christian Church. We belonged to the Ku-Mi-Ai-Kyo-Kai (Congregational Church), and Mr. Oda and Mr. Matsura were Christian, too. Reverend Fukushima wanted to have a church built here, so the Japanese in Fowler were divided into two groups. Until then, Christian and Buddhist met together, even though our beliefs were different. That’s how we were divided, though. Too bad.

From Fresno County Public Library – Japanese American Oral History Project, on September 1, 1980, Kazuo Hiyama talked about his childhood on the Fowler farm with Irene Eiko Kozuki.

Irene Eiko Kozuki: What have you been doing for most of your life?

Kazuo Hiyama: Well, I was born on a farm, and I helped my father work on the farm. At that time, I went to school, and there was a lot of discrimination, and we figured there was no possibility of getting a nice job, so I might as well be a farmer.

Kozuki: Can you tell us what you can remember about working on the farm?

Hiyama: I did mostly what my father taught me; cultivating, plowing, irrigating, and pruning. Most of it was hard work. There were no tractors, so we had to drive the horses and plow. All the irrigation was open ditches. We had to wake up in the middle of the night and watch the water at nighttime, and usually get up early in the morning. When I was going to school, we used to help before school and after school when I got back. We would help our parents.

From Fresno County Public Library – Japanese American Oral History Project, on August 14, 1980, Harry Echiyu Hiraoka spoke about his childhood in Fowler Japantown with Yoshino Hasegawa.

Yoshino Hasegawa: As a child, were there incidents or evidences of racial prejudice directed against you?

Harry Echiyu Hiraoka: Not so much in the elementary days. I think the big prejudices then were against the Germans, and what were we involved in then? World War I? So the Germans took the brunt of it. So I didn’t notice too much prejudice. I don’t know, I feel prejudice comes as a person grows. You feel it more. I wasn’t aware of it as a child but when I went to high school I began to feel it because I wanted to join the DeMolays and that was closed to other ethnic groups. There were so many things you couldn’t do–student body officers, you had to be white. I remember in high school I inquired of the Dean of Students at one time– if I wanted to teach Spanish in school could I get a job? And she said no, for those jobs you have to be Caucasian or white. So it was then when I really became aware that prejudice was there.

Hasegawa: Did you attend social functions when you were in high school?

Hiraoka: Yes, I attended social functions, but it was just a matter of tolerance, not so much of acceptance. They accepted you for your presence, but they never invited you to their homes at that time, or invited you to have dinner with them.

Hasegawa: According to the article in the PACIFIC CITIZEN, November 23, 1979, you were compelled as a result of your father’s illness, to quit your education at Fresno State and take over your family’s 80-acre ranch. What are some of the problems, difficulties, and responsibilities that confronted you, especially in view of the depression that gripped the country in the 30’s?

Hiraoka: That was quite an ordeal for an 18-year old, because I was aware of the prejudice that existed, and especially when you had to go borrow money to operate your farm. There was a difference–there was a racial thing that existed, and you never got what you needed. And if they gave it to you, they limited you in time to repay the loan. It was quite difficult.

Hasegawa: Do you think it was because you were Japanese that you had these problems?

Hiraoka: I think 90 percent of the problem was because of our ethnic origin. I would say so, yes.

Incarceration

The War Relocation Authority (WRA) shipped the Visalia and countryside residents to the Jerome concentration camp on the marshy delta of the Mississippi River’s floodplain. Its complex of blocks included barracks, mess halls, and latrines. The camp also had schools, a library, a hospital, a newspaper, a cooperative store, a Buddhist temple, a Christian church, baseball fields, and basketball courts. A temporary community council governed the concentration camp.

The WRA operated the Jerome concentration camp from October 6, 1942, to June 30, 1944. After its closure, most prisoners were shipped to the Gila River concentration camp in Arizona.

Resettlement

Despite the fear of hostility and violence, Harry Echiyu Hiraoka was the first prisoner to resettle in Fowler in December 1944.

Hasegawa: When you came back to California was your place still intact, was it still the same?

Hiraoka: Well, I gave them all the proceeds so I just told them to take care of it. I had interplanted grapes with trees, peach trees. I had Malaga grapes and in those days Malagas were worth a lot of money, because they had to dry most grapes and Malaga wasn’t a drying grape, so I believe the wineries paid $140- $150 a ton for them. I gave them all the crop, because I felt that no stealing was necessary. This gave them incentive to take care of the place, and all I asked them to do was to do a good job of taking care of it.

Hasegawa: And who took care of it?

Hiraoka: My neighbor.

Hasegawa: Then when you came back everything was all right?

Hiraoka: Yes, but he didn’t anticipate that we were going to come back and he was in hopes that he could acquire this property, too. This is what the white people thought–that we would never come back. So he was somewhat surprised when I came back.

Hasegawa: Kind of put out, I suppose.

Hiraoka: I imagine, yes, I would say so.

Hasegawa: Then you didn’t have any kind of prejudice when you came back?

Hiraoka: I had a lot of interviews–The Fresno Bee, and other news media wanted to know if I had any fears. I said, “If I had fears, I wouldn’t be here!” I think the only ones I had to fear was some of the Johnny-come-lately who came from Oklahoma, Texas, and other states and who didn’t know the Japanese people and those who wanted their property. This happened in Orosi because they didn’t know the Japanese, and if they did, they wanted their land. But I had no fears, and of course I had a host of friends also. No I wasn’t afraid. What happens happens– I’ve always been a fatalist.

Hasegawa: You didn’t encounter this personal anti-Japanese feeling then?

Hiraoka: Yes, it was there. I went into a plumber’s shop and they threw me out. Yes, it was there. And I stopped at a gasoline station and they said, “We don’t serve Japs!” So I just said, “Thank you,” and left–I made no big deal about it. After all, that’s his privilege if he doesn’t want to serve me. That fellow who threw me out of the gasoline station is a Shriner. He is a Mason and a Shriner. At that time of course, Japanese weren’t Masons. I am a Shriner now, and many times he calls me and I have to give some kind of excuse not to go with him because I haven’t forgotten. People don’t change that much. I have no antagonism, I just feel that I don’t belong with him.

Hasegawa: How long did this anti-Japanese feeling persist after the war?

Hiraoka: I’d say about 10 years. Then treatment became normal. There were so many new people who came into the area who were the big agitators. People who knew you were–in a year or so, learned to accept, but the new people, some of them who had taken over Japanese farms, and they just didn’t want us to come back! They rented it or some bought it for a song, so these people were mainly the agitators who were against our returning to California.

On December 25, 1944, from the Gila River concentration camp, Kazuo Hiyama resettled to his Fowler farm home with his wife, Edith, son, Howard, 5 years old, and daughter, Bemice, 3 years old. During their incarceration, C. K. Oliver had leased the 40-acre vineyard.

Kozuki: Would you say you had experienced any prejudice in buying any land or in trying to acquire more land?

Hiyama: That law that said you couldn’t buy any land until you were a citizen and aliens couldn’t own land. I guess that was what you call prejudice. Other than that, you had to work hard and banks wouldn’t loan you much money. It was all on a cash basis.

Kozuki: You told me earlier that the few instances you had experienced prejudice usually had to do with land transactions, and you mentioned an escheat case. Can you tell me about that?

Hiyama: When we got back from the war, the State of California wanted to escheat our land, because they claimed we had violated the law. So, they were going to take our land away. So we had an attorney Einer Nielsen to represent us. At that time, he recommended that we compromise with the state by paying approximately $1,500 cash, and that all would be forgotten. Then they gave us the right to the land.

Kozuki: Were those kinds of cases common then?

Hiyama: I don’t know, but I think there were quite a few.

Kozuki: Has there ever been any legal effort to get that money back?

Hiyama: I don’t think so. We settled out of court, so they didn’t pay too much attention.

Kozuki: Do you remember any prejudice directed at you after you came back from camp?

Hiyama: We used to get threatening letters, especially when this news got out that we came back to California. Three or four crank letters, but there were a lot of nice letters, too, and they sent us some gifts.

Kozuki: Do you feel you were taken advantage of as far as having your farm? Did you have any trouble because you were Japanese?

Hiyama: There was talk that they wouldn’t buy Japanese products, that they would discriminate against the Japanese. But it never did turn out that way. Most of them treated us pretty good.

Kozuki: You had no trouble selling your fruit, then?

Hiyama: No.

From Fresno County Public Library – Japanese American Oral History Project, on August 29, 1980, Harley Mitsugi Nakamura spoke about his resettlement in Fowler Japantown with Mikio Uchiyama.

Mikio Uchiyama: Do you recall any kind of discrimination aimed at you because you were Japanese-American?

Harley Mitsugi Nakamura: No, the only experience we had was when we got back from camp in 1946. We didn’t know it but some of the people living over here attempted to burn down the houses of the Japanese around here, and accidentally they burned the house across the street instead of ours. They thought that house belonged to a Japanese.

Uchiyama: Who did it actually belong to?

Nakamura: An Armenian family.

Uchiyama: That was the racial experience you had. Any other experiences like that?

Nakamura: No, not that I know of.

Uchiyama: What major ethnic groups comprise your neighborhood? What nationality?

Nakamura: Caucasians like Mr. Blayney, who really helped us out when we just came back; and Mr. Harding, another old-timer who took care of our ranch.

Uchiyama: You had a good neighborhood with the least amount of bad feelings?

Nakamura: Correct.

On February 10, 1945, shotgun blasts struck the house of Frank Osaki. Soon more, six shotgun blasts struck the house of S.J. Kakutani as the family were dining.

Hiyama Farms, Inc.

Since 1933, the Hiyama family has successfully farmed the rich soil of Fowler with orchards and vineyards. Kazuo Hiyama proudly reminisced about Hiyama Farms.

Kozuki: About farming. Since you have been doing this for so many years, could you tell us something about the changes you’ve seen in the industry?

Hiyama: Well, what I’ve seen is from horse and buggy to this modern mechanization where we get on a tractor and disc on it. In one day, you can get 80 acres done. But, basically, the raisin industry hasn’t changed too much as far as drying the raisin. So, recently, I’ve been experimenting with a method of trying to mechanize some of this hard work and some of the problems they’ve been having in the grape industry. Last couple of years we’ve developed some equipment, about four, and what is known as the Double T Trellis. There is a caneflipper, a sprayer where there is high volume and low pressure, some vertical striking rods for a harvester. This is for harvesting grapes for raisins.

Kozuki: Could it be used for anything else?

Hiyama: This trellis can be used for table grapes; also for winery.

Kozuki: So the basic change is the trellis?

Hiyama: Yes. Basically the trellis system. And then the equipment that we made.

Kozuki: Are these things patented?

Hiyama: We’re working on it now. We have a few patents already.

RECOGNIZING HIYAMA FARMS HONORABLE. GEORGE RADANOVICH OF CALIFORNIA IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Tuesday, May 1, 2001 Mr. RADANOVICH.

Mr. Speaker, I rise today to recognize Hiyama Farms for being named Industry of the Year. The Fowler Chamber of Commerce will present the award to Hiyama Farms at Fowler’s annual Community Recognition Banquet. Hiyama Farms is truly a family operation. Kazuo and Edith Hiyama purchased 20 acres of vines in Eastern Fowler during the 1930’s. Over the years the farm has gradually grown, increasing their acreage and focusing on growing tree fruit. The farm currently produces Zante currant raisins, cherries and tree fruit. Howard, the son of Kazuo and Edith, operates the farm with the help of his sons, Darren and Gene, and his brother Dean Hiyama. Hiyama Farms is one of the original growers to associate with the Fowler Packing Company and they share many of their innovative farming inventions with them. Kazuo invented agricultural equipment called ‘‘automatic movable platforms.’’ His invention greatly improved pruning and thinning of fruit trees. Before the advent of mechanized farming, Hiyama Farms utilized ‘‘dried on the vine,’’ mechanical raisin harvesters, and other efficient farming practices. The Hiyama sons’ current goal is to continue to improve the mechanization of the farm. These innovative farming methods singles out Hiyama Farms of Fowler as a leader in agriculture. Mr. Speaker, I rise to recognize Hiyama Farms for their Industry of the Year Award presented by the Fowler Chamber of Commerce. I urge my colleagues to join me in wishing the Hiyama family and Hiyama Farms many more years of continued success.

Fowler Buddhist Church

Since 1923, the Fowler Buddhist Church spiritually serves the Nikkei community of Fowler.

From Fresno County Public Library – Japanese American Oral History Project, on April February 13, 1980, in Fowler, the Honorable Mikio Uchimaya, judge, chatted about the Fowler Buddhist Church with Yoshino Hasegawa.

Yoshino Hasegawa: I see. Now what is the position of the Buddhist Church in the Fowler Community?

Mikio Uchiyama: Well, as far as a religious organization, the membership in the Buddhist Church, I think, has been highly respected. The opinions of JACL or the opinions of the Buddhist Church or Christian Church here, are all taken into careful consideration by the community. And the community more or less looks to them for some leadership. And we intend to participate in what goes on.

Uchiyama: There’s quite a few. As far as the Buddhist Church in Fowler is concerned, we have a hundred families, or thereabouts.

Hasegawa: The Buddhist Church, it seems to me, they are active.

Uchiyama: Yes, it is. It’s active in the sense because we have organizations starting from the junior YBA which is a younger group to senior YBA in adult group. And then the Buddhist Church women’s group, and then the Boy Scout group, so that there’s quite a bit of activity all the time.

Hasegawa: Would you compare it to the Mormon Church?

Uchiyama: No, we’re not that well organized. Again, the Buddhist Church is a voluntary membership so that we have our problems. Fowler Buddhist Church is a member of the Buddhist Churches of America but are not like the Mormons and its hierarchy.

Hasegawa: Well, I was thinking of the Mormon Church in terms of family and closeness.

Uchiyama: Well, yes, that’s there because the Japanese family like the Buddhist Church, you’ll find that Fowler, when something is going on like a community program, everybody helps and participates and everybody’s equal.

Hasegawa: What percentage of the Japanese in Fowler would you say are Buddhist?

Uchiyama: Maybe 90 percent.

Hasegawa: When did they start the Buddhist Church there?

Uchiyama: Oh, this was before the war, just before the war.

On July 10, 2023, during the Fowler Dharma School Centennial, Reverend. Brian Kensho Nagata wrote:

I recalled the history of our Fowler Sangha and the Fowler community, noting that Hoichi Sumida was the first Issei to purchase land in Fowler in 1889. Japanese Americans have been living in Fowler for at least 134 years. At one point in Fowler’s history, the mayor, judge, city attorney, and head of the hospital board were all Buddhists.

The beginnings of the Buddhist Church of Fowler go back to 1901 when Fowler became the first branch “Howakai” of the Fresno branch of the San Francisco Young Men’s Buddhist Association.

Once the Nisei generation started to emerge, Reverend. Itsuzo and Mrs. Kiyo Kyogoku of the Fresno temple encouraged members of the Fowler church to establish a Sunday School for the growing Nisei population.

The Issei and Nisei Farmers of California

Ron Inatomi, founder of Japanese Americans in the Produce & Floral Industry poignantly reflected:

The Issei and Nisei farmers farmed land nobody would consider. They saw beyond the brush, tree stumps, and rocks. They made the land fertile, growing unique fruits and vegetables in California.

They certainly had a green thumb, blood, sweat, and tears.

The farmers in the surrounding areas where the Japanese farmed were jealous. The pioneer Japanese fathers and mothers worked their fingers to the bone simply for the “Sake of the Children.”

The Isseis and Niseis farmed at all ten concentration camps, forever changing the agricultural landscape.

Before World War II, the Isseis and Niseis were responsible for 40% of the commercially grown produce in California. If left alone, there was no telling how far they would have succeeded, but the war brought it to an abrupt halt!

Over 120,000 Japanese (2/3rds natural citizens) were rounded up and placed in detention centers, with filthy conditions that reeked of animal urine and feces. They were transported again to the ten incarceration camps made in haste.

Our pioneers had to immediately figure out ways to cover openings in the wood to keep out the elements. Unbearably hot during the summers and unbearably cold during the winter, dust was in their eyes, nose, ears, and lungs. They had to contend with bugs and reptiles. Use the toilet and showers with no privacy. The War Relocation Authority said even if a person was 1/16th of Japanese blood must be incarcerated. They searched the orphanages and took away adoptees, too. Yet such a tiny fraction of the approximately 1.2 million Germans and approximately 1.6 million Italians living in America were incarcerated.

When they were finally released from prison, they were given $25.00 and a one-way transportation to their choice. In 1945, $25.00 is equal to $433.79 today. How could you reestablish yourselves with that amount in a hostile area, no matter where you went? Food, shelter, employment, transportation…I cannot comprehend it in my mind.

Close

Despite the loss of Fowler Japantown in 1942 during World War II and the denial of their American civil rights, the Japanese American community has shown resiliency. Hiyam Farms Inc. continues to succeed in the agricultural business, and the Fowler Buddhist Church continues to serve the Nikkei souls.

We went through some hard times, but I think it’s those rough times that make you work harder. When you’re hungry, you try harder. I think it’s a good philosophy. You have to suffer to know what real hardship is. When you attain it, you really appreciate it.

Kazuo Hiyama, Hiyama Farms Inc. founder (1980)

AsAmNews is published by the non-profit, Asian American Media Inc. Follow us on Facebook, X, Instagram, TikTok and YouTube. Please consider making a tax-deductible donation to support our efforts to produce diverse content about the AAPI communities. We are supported in part by funding provided by the State of California, administered by the California State Library in partnership with the California Department of Social Services and the California Commission on Asian and Pacific Islander American Affairs as part of the Stop the Hate program. To report a hate incident or hate crime and get support, go to CA vs Hate.