By Dianne Fukami

(This is part of our ongoing series, Lost Kinjo- a look at the more than 40 Japanese communities that disappeared after World War II. It is supported by funding from the California Public Library Civil Liberties Project and the Takahashi Family Foundation.)

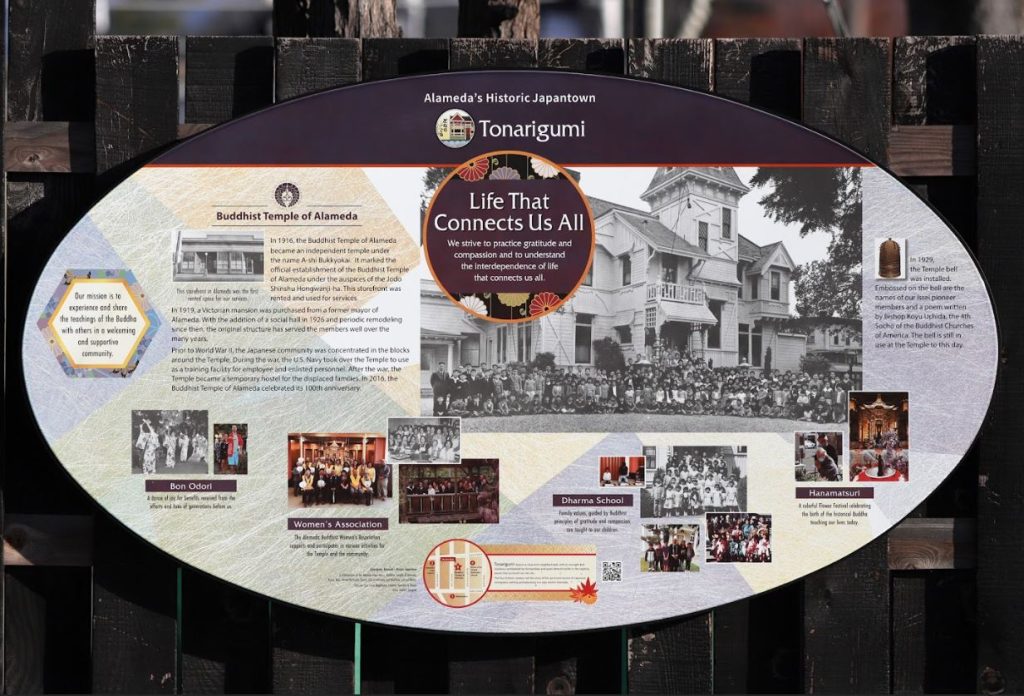

In the East Bay city of Alameda there are new reminders of the Japantown that used to exist there. Four historical markers are placed at landmarks in what used to be Japantown, attempting to tell the story of the thriving Japanese American community that was never the same again after World War II. Known as the Tonarigumi “neighborhood association” project, the first marker was unveiled in November 2023 at the Alameda Marketplace, the heart of old Japantown.

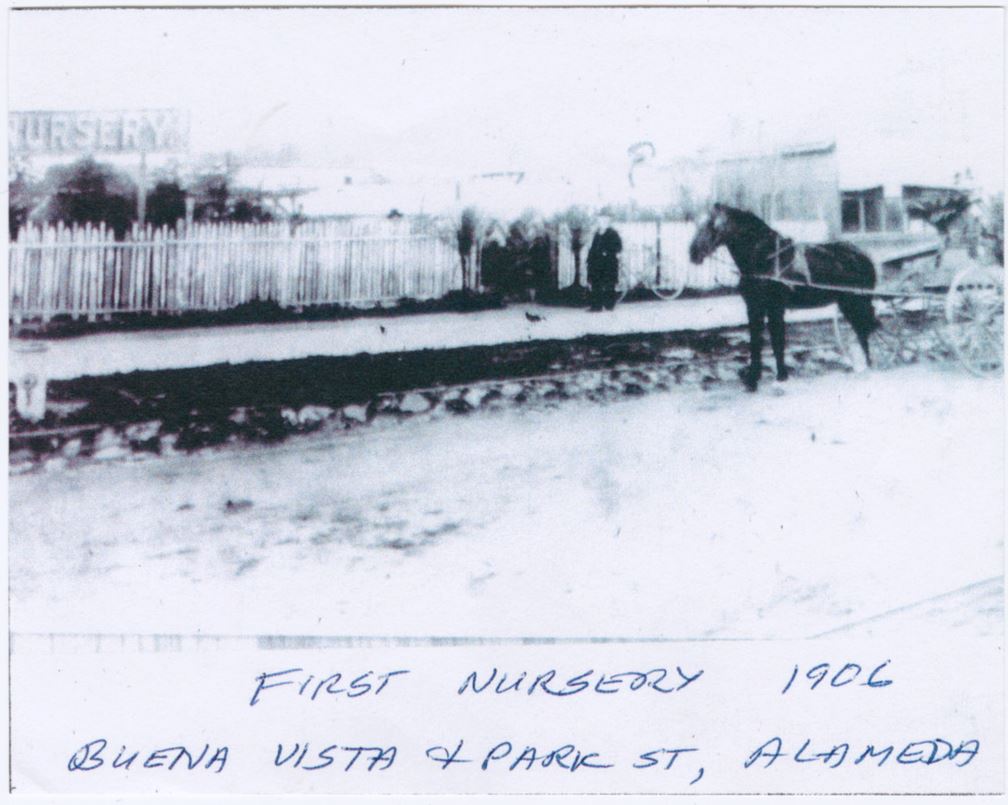

The first known Japanese immigrant to Alameda was Hirokichi Hayashi, who arrived in 1889 and opened a plant and retail store. Alameda had only become an incorporated city in 1872, and its population started growing in the 1860s as people working in San Francisco and Oakland found easy transportation to their jobs.

By 1893 Hayashi was joined by other Japanese immigrants, most of them like he, from the Fukuoka prefecture in Japan. Eisaburo Tomoeda opened a shoe repair shop, Masataro Sato had his grocery store, the Narahara Hotel opened on Park Street, and a group of the Gakyu-Kai was formed by a group of Japanese school boys living in Alameda. (Note: in that era a “school boy” was a houseboy student, generally for wealthy families in San Francisco, who went to school by day and worked as domestic houseboys.)

LATEST STORIES

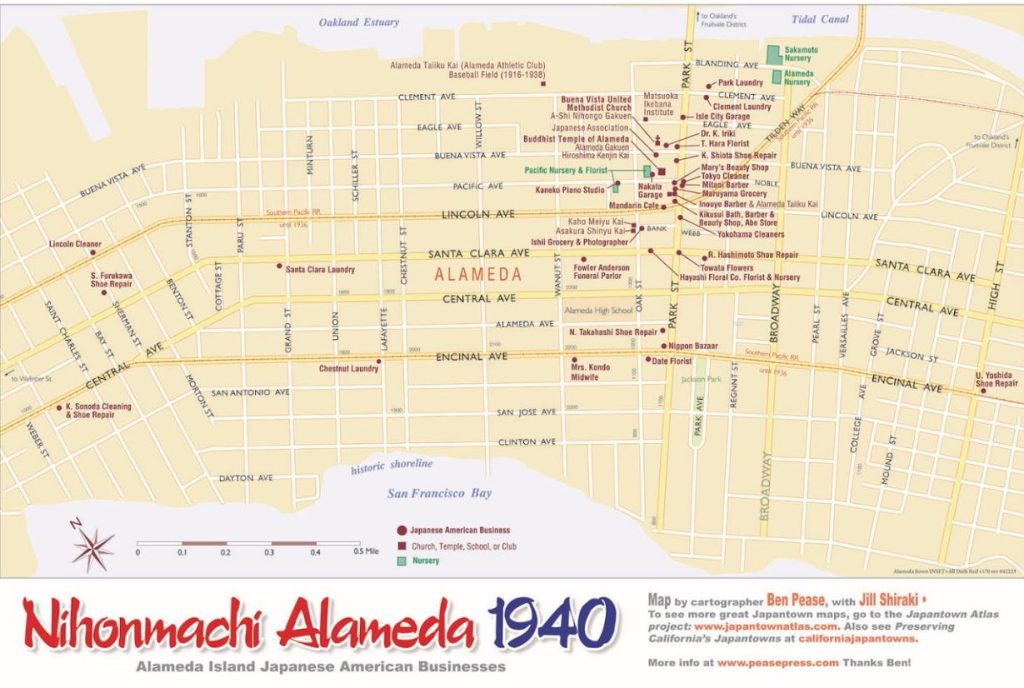

This burgeoning Japanese community was roughly bounded by Park Street, Santa Clara Avenue, Walnut Street, and the Oakland Estuary, with businesses mostly on Park Street between Pacific and Santa Clara streets, due to discriminatory covenants in place at the time, restricting where Japanese could live and run businesses.

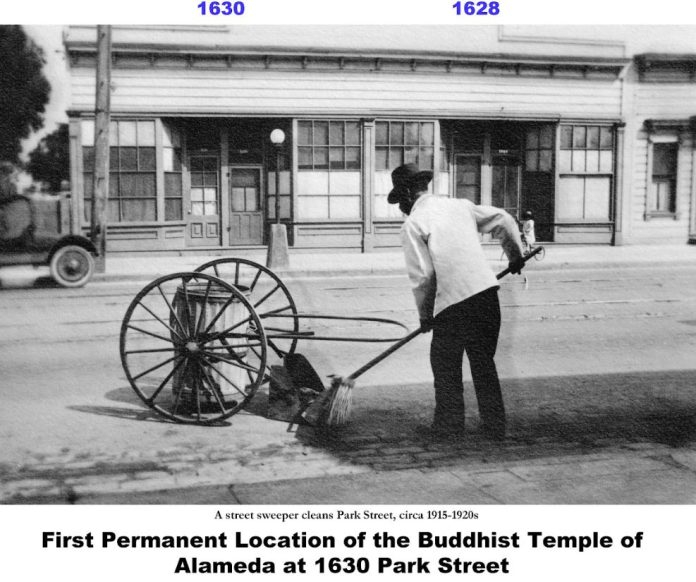

Over the next ten years more Japanese moved to Alameda and in 1904 the Japanese American population was reported at 325. The Methodist church, which would become Buena Vista United Methodist Church, was established in 1903, and along with the construction of the Buddhist Temple of Alameda in 1916, helped anchor the community.

As the community grew, so did discrimination against Asian immigrants. In 1790, the Naturalization Act set the course for racist policies by allowing only White immigrants to apply for citizenship. The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 prohibited Chinese laborers from entering the U.S., and when Japanese workers filled labor demands, it resulted in the 1907-1908 Gentlemen’s Agreement between the U.S. and Japan, an informal agreement whereby the U.S. would not impose immigration restrictions on the Japanese if the government agreed not to allow anymore emigration to the U.S. In 1910, the City of Alameda proposed an ordinance that would ban Chinese and Japanese laundries, although it appears it did not officially become a law. In 1913, the California legislature passed the Alien Land Law, which prohibited “all aliens ineligible for citizenship” from owning property, which included Japanese immigrants, who were not allowed to become citizens according to the Naturalization Act, which was upheld in 1894, and again in 1922. In 1924, the U.S. Congress passed the Immigration Act, which closed the door to all Japanese immigration to this country.

Yet Japanese American communities such as Alameda’s Japantown persevered. Initially most Japanese immigrants were men without families and as the restrictions on Japanese migration to the U.S. tightened, the concept of “picture brides” became popular. As most marriages in Japan during that era were arranged by families anyway, the idea of a Japanese man in America agreeing to marry a woman from Japan just by seeing her photo did not seem so far-fetched, if the woman in the photo agreed to leave her homeland to cross the Pacific to marry a man she also only knew from his photo. Despite the racist immigration and citizenship laws, Alameda’s Japantown community thrived. Census figures show that in 1910 there were 500 people of Japanese ancestry, that number increases to 600 by 1920, and goes up to 800 in 1930.

A map prepared in 2007 by the Japantown Atlas project shows a 1940 snapshot of the Japanese American businesses in Alameda. Along Park Street, there were several barber and beauty salons nestled among the various floral businesses. The northern part of Japantown was anchored by the Buena Vista United Methodist Church and the Buddhist Church of America surrounded by a cluster of community groups such as the Japanese language schools Ashi Nihongo Gakuen and Alameda Gakuen, the Matsuoka Ikebana Institute (Japanese flower arranging), the Japanese Association, and the Hiroshima Kenjin Kai, an association of people originally from the Hiroshima prefecture from Japan; its presence indicates that although the earliest Japanese immigrants may have come from the Fukuoka prefecture, through the years enough people came from Hiroshima to warrant organizing their own group.

Young children attended Porter or Haight grammar schools while the teens went to Alameda High School right in the neighborhood; most went to Japanese language classes right after school. In the 1930s and early 1940s, Japanese Americans had everything they needed right in their Japantown: groceries at Maryuyama or Ishii Groceries, maybe a bite to eat at the Mandarin Café, shopping at the Abe Store or Nippon Bazaar, and a variety of shoe repairmen to choose from including Shiota-san, Sonoda-san, Hashimoto-san, and Yoshida-san. Ladies and gentlemen had choices among the neighborhood beauty salons and barbers. As Japanese began to make inroads into the Bay Area floral industry, more florists and floral businesses sprang up in Alameda. As for family expansion plans, Mrs. Kondo was there to offer her midwifery services.

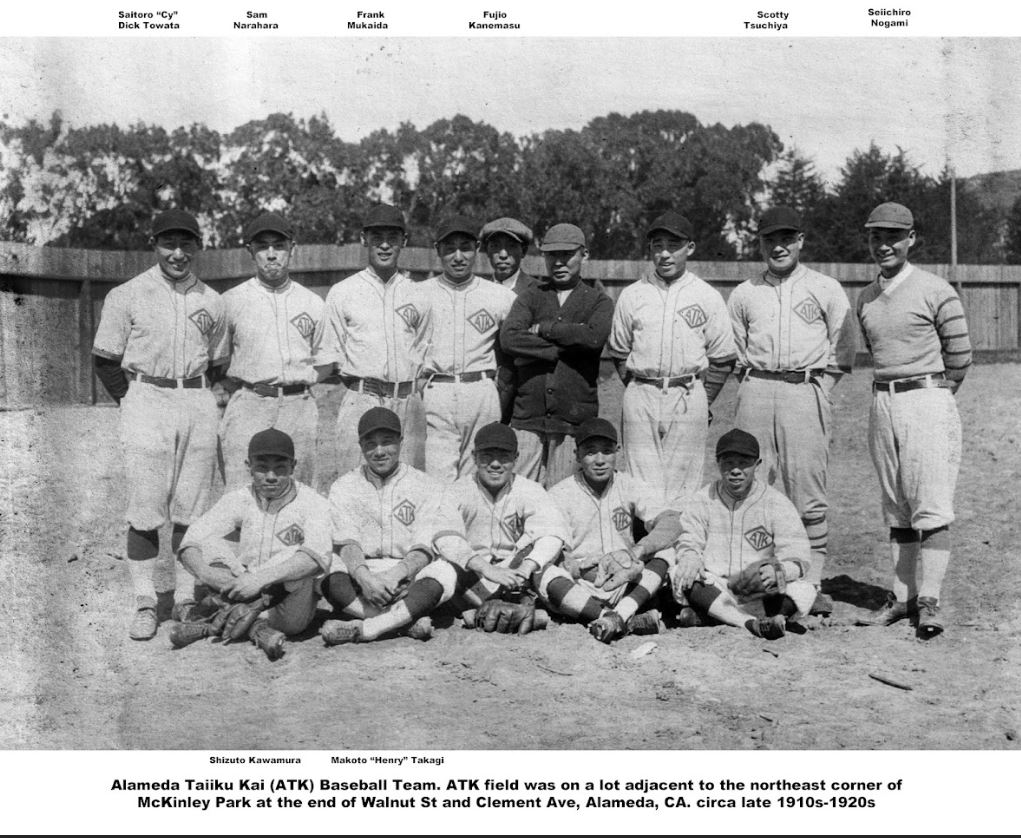

No matter the religion, beauty salon alliances, or what prefecture origin, nearly everyone supported the Alameda Taiiku Kai (Athletic Club), which shared space with the Inouye Barber Shop on Park Street, and managed a baseball field at the edge of Japantown on Clement Avenue and Walnut Street, the land loaned to them by James Rolph, Jr. a former San Francisco Mayor and California Governor, who owned a shipyard along the Alameda estuary. According to a 2000 article in the Alameda Museum Quarterly, the roots of the ATK go back to 1913 when the first-generation immigrants or Issei formed a baseball team, which later became the Alameda Young Men’s Buddhist Association Baseball Club in 1916. But to include players from the Methodist church, the team changed its name to Taiiku Kai (ATK). Playing other Japanese American teams from the Northern California Baseball Federation, the ATK team filled the stands during their home games with fans cheering for stars that included Sai “Dick” Towata, Mike and Mas Nakano, Taro Takeda, Sam Rokutani and Kiyo Nogami, both of whom played on the UC Berkeley baseball team.

All that ended on December 7, 1941 when the Japanese Imperial Navy bombed Pearl Harbor. Like other Japanese American communities located near military installations, Alameda was one of the first areas impacted by Executive Order 9066, the presidential action resulting in the removal of people of Japanese ancestry from the West Coast during World War II. Immediately after the bombing of Pearl Harbor the FBI arrested leaders in Japanese American communities throughout California, Alameda being no exception. But even before Executive Order 9066 was signed by President Franklin Roosevelt on February 19, Issei in Alameda were excluded from the western part of the city four days prior and ordered to leave Alameda by February 24.

(Japanese Americans living at Terminal Island in Southern California and Bainbridge Island in Washington were also ordered to leave their homes sooner than other communities because of their proximity to the open water amid concerns that Japanese Americans would try to signal and contact enemy Japanese.)

Shigeki Sugiyama was 15 years old at that time and in 2010 told the Manzanar National Historic Site Collection “So some people moved into Oakland, San Leandro, down into what is now Fremont. And they’re the ones that wound up in Topaz, others, there’s some, a few of the citizen Nisei who stayed in Alameda until they were relocated into assembly camps and so forth. My father had a friend in French Camp and so arranged, then found a place, a vacant farmhouse out there and so we moved to French Camp …and then when it came to go into camp, the people around us, I think, went into the Stockton Assembly Center and there one strip that was left, and I thought, oh, maybe they forgot us, you know. And then we got order to go to Manzanar.”

But other families, like the Takanos traveled 12 hours by car to get to the central valley town of Cortez. In interviews with the Alameda Japanese American History Project in 2022, Mas Takano and sister Cookie Takeshita explained their family of five fled to Cortez based on a friendship their father had made many years previously. They believed it was a temporary measure and would soon be allowed to return home to Alameda, so didn’t pack up all their possessions. However, the Takano family were only there for a few weeks when they received notification to report to the Merced Assembly Center, where they were detained until they were transferred to the Amache camp in Colorado, never able to return to their home in Alameda to reclaim and pack the things they’d left behind.

Leaving Alameda

In Alameda, there were two main waves of departures: the first wave that focused on the Issei immigrants and their children, and the second wave that included the adult Nisei who didn’t leave their homes and businesses until they received their removal orders to report to Assembly Centers. For most, that meant the Tanforan Racetrack in San Bruno, down the San Francisco Peninsula. Multi-unit barracks were built on the racetrack’s infield, but many families were assigned to live in whitewashed horse stables. It took several months for buildings and infrastructure to be constructed in the concentration camps created for Japanese Americans, so in the interim, they lived at the Assembly Centers, which were mostly fairgrounds and racetracks in various parts of California that had been hastily converted to house and imprison the 120,000 people who were of Japanese ancestry.

After several months in the temporary Assembly Centers, the Japanese Americans were transported to the concentration camps, where most were imprisoned for the duration of World War II, some three years later. Although the U.S. government tried to keep communities together, it was difficult in the case of Alameda residents. Many of them had dispersed during that first wave of forced removal and were scattered and when the eviction orders came to report to an Assembly Center, generally people were assigned to the Center closest to them. Most of the Japanese Americans from San Francisco and the East Bay area, which included Alameda, were ordered to the Topaz Relocation Center, in the middle of the Utah desert. But unlike other community neighborhoods that were assigned to live in blocks of barracks together at the camps so they could retain a sense of community, the former Alameda residents were assigned randomly to barracks throughout the camp, so without familiar faces, the isolation often felt more severe.

War Relocation Authority records show that half of the pre-war Alameda residents ended up at Topaz, while 19% were incarcerated at Gila River in Arizona, 9% at Heart Mountain in Wyoming, and 9% at the Tule Lake Segregation Center at the California/Oregon border. Another 12% were dispersed throughout the other six concentration camps.

Young adults and students tried to get out of the camps as soon as they were able by attending a college in the Midwest or East Coast or by getting work permits to get jobs in the interior of the country. Many did not return to Alameda at war’s end. Arthur Tadashi Hayashi resettled in Detroit before he was drafted and served in the Military Intelligence Service before making his way back to the Bay Area and settled in Berkeley with wife Fumi Manabe. WRA records show that 211 people returned directly to Alameda after camp, which was about 25% of the pre-war population that lived there. Reverend Shigeo Shimada, who had been the minister at the Methodist Church, went to San Francisco with his family after being released from Topaz, and then moved to Washington where he continued to minister.

It was mostly the elderly and parents of young children who stayed until the camps closed in 1945 and they were allowed to return to the West Coast. As they made their way back to their homes by train or bus, they faced prejudice and discrimination which did not always improve once they reached the communities they had been forced to leave more than three years earlier.

Mas Takano’s family was one of the first to return to Alameda and he recalled the treatment he received at Alameda High School from the other students: “They would bump you in the hall and they’d say a snide remark. But I used to say, they best day I had is when people ignored me. Basically it was true, best day. And then they used to chase me home from school. But that only lasted about three weeks, and then people started coming back. So we had about three or four people my age. And out of the three or four, two of them had never, were not Alameda people. It just said there was a hostel they could go into and so they came over. But they were my age, so it was good. So we looked out for each other, it was nice.”

A listing in the Densho Encyclopedia reports that Norichika Akamatsu was the first member of the Alameda Methodist Church to return to Alameda, preparing quarters that could serve as a hostel for the returning Japanese Americans. The rental homes the Issei had rented before the war were no longer available, a new crop of workers who had migrated to the San Francisco Bay Area to work in the shipyards, and number of returning Japanese Americans all contributed to a housing shortage. Jo Takata and sister Judy Furuichi remembered being one of the four families that lived in the church cooking and sharing meals together and living communally until their family was able to buy a home just two doors away in 1952.

Kiyo Sato Matsuda talked about a similar situation across the street at the Alameda Buddhist Church during her 2021 interview with the Alameda Japanese American History Project: “So we came back to Alameda, and when we came back, of course, there was no place to live. And so this Buddhist temple was open and we stayed here for about five months or so, and lived in the hall with a number of other families. And I remember all the ladies had to cook together in the kitchen. There were the Sugiyama girls, Kiyomi and Satoko. And then there was the Marubayashis, and Mamie and all of her sisters.”

The Alameda Japantown community tried to knit together again, but without the vibrant pre-war retail scene, it wasn’t the same. 75% of its residents hadn’t returned however those who had created a strong bond as Joe Takata recalled: “Everybody knew what was going on, and our house was Grand Central Station. I don’t want to call it the heartbeat of the community, but it really, because it was across the street from the Buddhist temple, two houses away from the Methodist church, and so it was a place where people congregated daily. Not just on Sundays, but daily. And I would come home and there would people around the table in the kitchen having tea or coffee and just talking, and I think they have a sense of community, and I think that’s what I love the most is that they encouraged each other, they had each other’s back, in other words. They knew their struggles, and so they were, had what they call this tonarigumi, this sense of community and this sense of helping each other.”

Not all of Alameda was happy that the Japanese Americans were back on the West Coast. Even 15 years later, discrimination still existed, as Mas Takano and his family experienced in his oral history with the Alameda Japanese American History Project: “And in about 1961 or two, I guess they started to look for a home in Alameda. One year I couldn’t find the house. They wouldn’t show me a house, there’d be an open house, I would go in, and I put in our bid. And I called, and they would say, ‘We never got your bid.’ Real estate people just chuck it out. And I had my hakujin friends, by this time I had a lot of hakujin (Caucasian) friends and we’d go in separately and they’d put in a bid and they would be always undermine. I’d tell them I’m going to bid this. They would get a call saying, ‘We got your bid.’ They wouldn’t call me.” Through sheer tenacity, Takano ended up becoming the first non-white to buy a home east of Broadway, outside of the traditional red-lined area for Japanese.

Although the postwar Alameda Japanese community was smaller, it remained anchored by its two churches, the Buddhist Temple of Alameda and what has become the Buena Vista United Methodist Church, which have become the nexus of several projects that preserve the history of Alameda’s Japantown. The 2023 Tonarigumi historical marker project is the most recent to memorialize the area, with the four markers placed in old Japantown at the present sites of the Alameda Marketplace, the Alameda Free Library on Oak Steet, the Buddhist Temple of Alameda on Pacific Avenue, and the Buena Vista United Methodist Church on Buena Vista Avenue. The descendants of the Issei immigrants and their American-born Nisei children continue the work of remembering and protecting the legacy of the Japantown that no longer exists.

AsAmNews is published by the non-profit, Asian American Media Inc. Follow us on Facebook, X, Instagram, TikTok and YouTube. Please consider making a tax-deductible donation to support our efforts to produce diverse content about the AAPI communities. We are supported in part by funding provided by the State of California, administered by the California State Library in partnership with the California Department of Social Services and the California Commission on Asian and Pacific Islander American Affairs as part of the Stop the Hate program. To report a hate incident or hate crime and get support, go to CA vs Hate.

Although I was born and raised in San Francisco, I lived in Alameda 1985-1988. I never knew about the Japanese neighborhood here. I remember that living on San Jose Ave east of Broadway, I was the only Asian in the neighborhood. So much information in this article. Thank you!