By David Hosley

(This is part of our ongoing series, Lost Kinjo- a look at the more than 40 Japanese communities that disappeared after World War II. It is supported by funding from the California Public Library Civil Liberties Project and the Takahashi Family Foundation.)

When he looks out over his vineyard on the west side of Lodi, Jason Mikami may sense the grapes in his DNA. For almost as long as vines have been planted in the special soil near the Mokelumne River, his family has taken care of vineyards in the area—more than 125 years that traces back to before Lodi was a city.

There are three missing years in that span of time, the years when his grandparents and their children were incarcerated during World War II because they were Japanese and lived in Lodi.

LATEST STORIES

That history is important to Mikami. So are the vines and his Japanese American family’s connection to the land. He cherishes his upbringing in Lodi and has found a way to be both a leader in technology for Uber while also making award winning wines with his family at Mikami Vineyards.

As unique as Mikami’s career is, the story of his grandfather’s coming to Lodi is trailblazing, too. It is wrapped up in a place that wouldn’t have a Japantown except for some farmers who had a wild idea about starting a city from scratch.

Japantown Linked To Central Pacific

Like a number of places in California, the building of a rail line played a central role in the development of northern San Joaquin County. As the transcontinental railroad was nearing completion in 1869, Central Pacific Railroad planners decided to connect Stockton and the rail yard in Sacramento with a feeder track. Civic leaders who lived around Turner Road wanted to have the train stop in their area, and offered Central Pacific 160 acres, with 12 reserved for a station and switching tracks in its heart. The stop would be called Mokelumne Station, as the new town would also be named after the nearby river.

The rail line was largely built by Chinese laborers, some of them likely veterans of the perilous Sierra construction marvel. Also in 1869, a group of Japanese fleeing the fallout from a power struggle among samurai had established the Wakamatsu Tea and Silk Farm in Coloma, adjacent to the foothills mill where gold was discovered. The Wakamatsu colony became the first Japanese community in the state.

Some of the Central Pacific construction crew may have remained as the first Chinese residents of the new town in northern San Joaquin County. Others may have been attracted by the need for workers to build out Mokelumne. With a link to the transcontinental railroad, local farmers could send a variety of crops in just days to new markets in the center of the country and up and down the coast.

Because other places in the region also had taken the river’s name in some form, Mokelumne soon became Lodi to differentiate it. Chinese shops, restaurants and lodging were established on streets close by the rail yard. They were welcome, but not by all and only to a point. An economic slump in the 1870’s increased competition for jobs, and a new California state constitution in 1879 forbid hiring any Chinese.

A federal exclusion act in 1882 severely limited immigration from China. So California farmers increasingly turned to Japan for a labor supply. Japan had its own social upheaval as Emperor Meiji sought to modernize the country in the 1880’s, which largely left behind farmers in the south. First generation Issei farm laborers were brought to Hawaii, then a nation, with some continuing after a while on to California. Soon farm workers were recruited directly from Japan to the U.S. west coast. A half dozen Japanese workers, for example, came to Lodi in 1890 to work in the Delta’s sugar beet fields.

American Dream

In Lodi, new arrivals from the Hiroshima region settled in or adjacent to Chinatown, or in camps out in the country closer to fields they would plant, water, prune and harvest.

One of them was Teruichi Mikami, who had entered the U.S. at Tacoma, Washington on May 11, 1896 and made his way to nearby Kent in the White River Valley. Kent was south of Seattle and had a growing Japanese population. Some Caucasians there felt the first-generation Issei were taking jobs that should belong to them. A campaign launched by an anti-Japanese organization urged farmers “to discharge their Japanese labor.”

It’s not clear if xenophobia in Kent played a role in his grandfather’s coming south to California’s Delta region. Jason Mikami told AsAmNews that the family’s coming to America story isn’t more specific than a 15 year old boy wanting to build a better life by fulfilling the American dream. It is documented that Teruichi Mikami found a Japanese community in Lodi of at least 50, one that had been started in 1885.

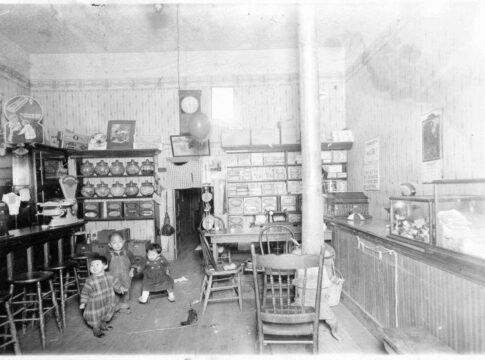

One of the first buildings to go up was the Hinode general store in 1890 on Main Street. Typically businesses operated on the ground floors in Lodi’s Japantown, and second stories were living quarters for the owners, or rented to lodgers. The store’s owner was Seijiru Masui, who went by “Joe.” Masui had come from the Hiroshima area in the 1880’s to Seattle. He worked for a while in Puget Sound and then relocated to do farm labor near Walnut Grove, where he also recruited laborers for farmers. Masui then worked on a farm northeast of Lodi. Wrangling labor gangs plus field work brought in enough cash to open the store.

The wooden structure burned down in 1896 but a two-story building made of concrete blocks replaced it. Masui’s family in Japan arranged a marriage to Yoshino Nagano. After settling in, she became “Mary.” Japantown grew up around the store, just east of the railroad tracks, interspersed with Chinese stores and houses. Joe Masui ran into financial troubles and his store went under in 1910. It subsequently became the Miyajima general store operated by Shokichi Wakai, with a hotel and card room and bar upstairs run by Kenichi Tamura.

Agriculture Focused On Tokay Grapes

Lodi had been growing steadily, and in 1906 it officially became a city. Voters were very much in favor of incorporation although the Japanese residents, because they were not citizens, could not vote. The city got trolley service in 1907, and that year also saw a celebration of the area’s most famous product, with a multi-day Tokay Carnival. A grand arch was constructed for the event, and everyone in Japantown could see it across the rail yard.

Tokay grapes had been planted in the northern San Joaquin River region as early as the Gold Rush, along with the Mission variety that had been planted along California’s coast and Napa Valley. But it was dry wheat farming that first dominated mechanized agriculture around Lodi, and then watermelons. By the time Teruichi Mikami arrived a few years prior to 1900, the Flame Tokay was ascending, named for the distinctive color of its thick skin.

Traced back to northern Africa, the Tokay vines flourished in the sandy loam of riparian habitat created over eons by the rivers in the region. Popular as a fruit eaten out of hand, the Tokay had also been made into wine by the Spanish settlers who came up from Mexico a century before Lodi was settled.

But its value, when Japanese immigrants became the primary farm labor force, was as a table grape, with trains taking carloads to the Bay Area, Los Angeles and even north to Portland and Seattle as well as over the Sierra to eastern markets. One such journey to New York reportedly took 16 days.

The newcomers from southern Japan brought skills, or soon learned them, that were essential to successful cultivation of grapes, including care of the root stock, the training of vines, trimming shoots, and then the all-hands push to harvest at peak flavor. Grapes required an investment. It wasn’t like wheat where you cast the seed in the spring after hoped for winter rains, and then harvest in summer or early fall. Vines needed years before reaching maturity, and more attention than watermelon, too.

On the one hand, the owners of farmlands wanted a predictable, and affordable, work force. On the other, California was at the forefront of anti-Asian discrimination in the early part of the 20th century, and opposition burned more brightly in the Central Valley than the coastal regions. Those dynamics clashed repeatedly, and for decades.

Alien Land Law Of 1913

The California Alien Land Law of 1913 restricted immigrant purchase of property. It was a descendent of discrimination against Chinese immigrants going back to the Gold Rush. Oregon’s constitution, written in 1859, specifically forbid land ownership by Chinese. In 1879, California lawmakers revised the state constitution, limiting property ownership to aliens of “white race or of African descent.” The state of Washington adopted legislation in 1886 that was echoed in later laws, in more than a dozen other states, prohibiting “aliens ineligible for citizenship” from holding property rights.

General in language, California’s new alien land law in 1913 was aimed directly at the first generation of Japanese immigrants without specifically mentioning them. The measure also forbade the ineligible aliens from holding long term leases. Still, Japanese immigration increased in the decade before World War I.

Young men who took a chance on a better life in America often had marriage in mind, many of them arranged with Japanese women willing to emigrate. One of those brides was Mitsuyo Shintaku Mikami. It was an arranged marriage, and she was 15 years Teruichi’s junior.

The marriage took place in Hiroshima Prefecture without the groom present on July 10, 1918. Mitsuyo arrived in the U.S. on May 15, 1919 on the ship Korea Maru. Only a year later, Teruichi was renting a farm on Cherokee Lane in the O’Neal township. And the Mikami’s were about to have their first child, Matsuto. They were doing well enough to have two hired hands, named Shiboto and Nakamoto, living on their place. Their neighbors, according to the 1920 census, were named Masui, Matsubayashi, Teranishi and Danube. The latter likely reflected a significant German immigrant presence in Lodi.

The children of those marriages of Japanese immigrants, born in America, became a way to get around the alien land laws because of the 14th amendment of the U.S. Constitution, which had been ratified in 1868. All persons born in the U.S. were citizens, its first section stated, and no state could deprive them of property. A good number of second-generation Nisei, most of them boys, were therefore named in deeds as owners because their parents could not be.

Vibrant Community

There was palpable growth in Japanese communities in California in the 1920’s and 30’s as offspring became school age. By the mid-20’s, six blocks of downtown Lodi had Japanese businesses, ranging from a number of restaurants, hotels and rooming houses to a pool hall, tofu store, laundry, and a garage. And between those business and the train tracks, now leased by Southern Pacific, a line of fruit packing sheds provided seasonal work.

By 1930, there were many activities Japanese American families could pursue, including Japanese language classes, sports, youth groups and social clubs. Lodi fielded teams that competed against other Japanese community squads from Fresno to San Jose in basketball, baseball and track. Masato Yamashita liked baseball the most. It was always a part of his life in Lodi, as the ball club had started in 1915 before he was even born.

Things had changed a great deal for the Mikami family by 1930’s census. They were renting on Woodbridge Road in Liberty township, and now had six kids under 10. Teruichi’s vocation was listed as laborer. Things weren’t easy as the Depression bore down. It was changing the work force in the Central Valley, too, as tens of thousands of Okies made their way west, looking desperately for a way to make a living.

Center of Anti-Japanese Sentiment

Lodi’s Japanese community was surrounded by cities and towns with their own Japantowns by the 1930’s. Its members could go to Stockton or Sacramento’s vibrant Japantowns to shop for larger purchases, festivals and entertainment. As the northern most city in the San Joaquin Valley, Delta towns like Walnut Grove and Isleton were close enough for a visit on weekends. It wasn’t unusual for residents from those places to come to Lodi for work at harvest time, or to socialize.

But never far from mind after World War I was the rising tide of bias. California’s Alien Land Law was amended in 1920 to expand limits on leasing land to Issei. There was support from both agricultural organizations and business leaders to limit the number of immigrants coming to America. And the conservative farmers of the Central Valley were very much interested in holding on to power, both economic and political.

Every year in the early 1920’s, legislation was introduced to cap the number of immigrants, especially from Japan. Newcomers from Italy and others from southern Europe were targets of the laws, too, but in California the focus was the Orient. No one from Asia, with few exceptions, could immigrate if they were an alien who was ineligible for citizenship based on race or nationality, because 1924 Immigration Act incorporated the existing Asian Exclusion Act and the National Origins Act.

High Mark for Japanese Community

A Japanese community icon emerged in Lodi in the late 1920’s. Buddhists had been residents of Lodi for four decades, but the closest Buddhist church had initially been in Sacramento, with a Stockton church formed by 1910. There was a desire to have a place of worship in Lodi, with several efforts, until a church was formally established in 1929. A women’s group was started, and youth groups followed under the first minister, Kensei Nakamura.

The impact of the church went beyond religious observance. It was a social hub for many of Japantown’s families, and an important conduit to Japanese language and cultural traditions for children and adults in the area. It was a place where teens could come together, and where women had a place to socialize. And the church building was right in the heart of Japantown, a central location for a range of community gatherings.

Ironically, Lodi’s Japanese community reached its peak while repeated legislative measures were adopted in Sacramento and Washington, D.C. that effectively cut off newcomers from Japan. The growth during the Depression came instead from the first-generation having children, offspring who were citizens by birth, bilingual, and bi-cultural.

The second generation, the Nisei, often excelled in the classroom and had a much greater range of vocations available to them than their parents. While Japanese Americans families struggled during the Depression, as did the majority of Americans, a better day seemed ahead. As the decade of the 1930’s came to an end, life in a region whose economy was driven by agriculture looked up. San Joaquin County was among the top four counties in ag production in California. And a leader in a state that grew half the nation’s grapes.

Assembled in Stockton

Henry “Gary” Shioto was in his mid-teens when Pearl Harbor was attacked. He was living with a Japanese family in Lodi, as his mother was a widow working to support her family as a cook in farm worker camps out in the countryside. “I was making the crates to put lettuce in,” he recalled in an oral history. “And I heard the cries of Extra! Extra! with the papers coming out. My first thought was that Japan had done something wrong.”

The next day was a Monday, and Shiota went to school at Lodi High. “I just went about my business…my German and Italian friends didn’t treat me any different.” The federal government limited travel for persons of Japanese descent on the Pacific Coast, and then added a curfew that included Lodi, where about 800 Issei and Nisei now resided.

Rumors were rampant within the Japanese community about what might happen. Next steps as the government was mobilizing for war were unclear. Some of the Nisei contemplated leaving for states to the east, hoping they would be safer there. But most in San Joaquin County kept their heads down and prepared for the planting season.

Ironically, Matsuto “Jimmy” Mikami, who had graduated from Lodi High in 1940, and other Japanese Americans of draft age were required to register. He was 21 years old when he filled out the form on February 16, 1942, working for prominent grape grower and shipper Ed Kurtz and living with his parents and siblings on a rented farm in Acampo, north of Woodbridge.

Three days later, President Roosevelt issued an executive order for the forced removal of Japanese and Japanese Americans from the west coast of the country. The details weren’t known, but many of those soon to lose their freedom tried to salvage some of the value of their possessions, or secure places to store their most cherished items. Teruichi Mikami had purchased a new car, which would be in his possession for only a month.

A graduate student who studied sales of Japanese and Japanese American owned property in the region before, during and after incarceration, Frederic Wilson, observed that Lodi was an exception is one respect. Rare among Japantowns in California, almost no property in the city’s Japanese neighborhood changed hands in 1942. Of the 15 Japanese and Japanese Americans owning buildings, as well as one church and two corporations, only one was sold.

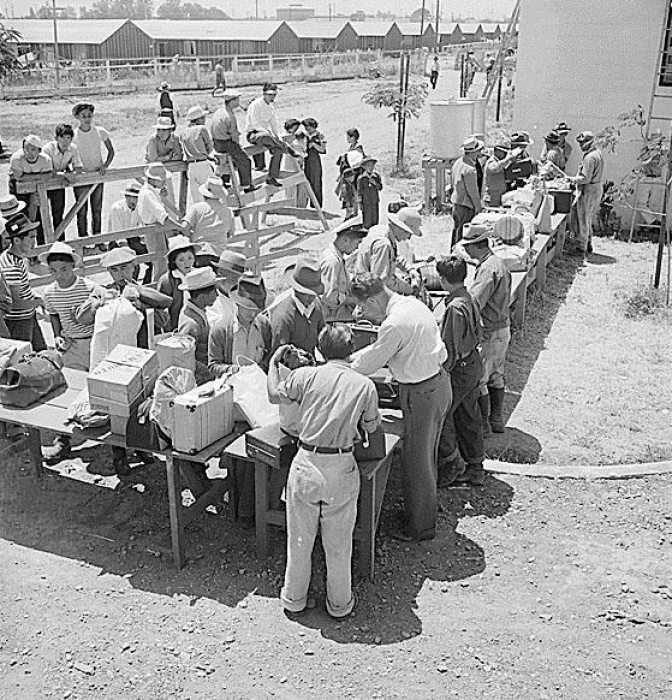

In early May, Gary Shioto learned the specifics of incarceration when notices to report to the Stockton Assembly Center were posted on telephone poles and fences in Lodi. “Our background was when someone in authority tells you to do something, you do it.”

One of his memories of that time were his brother and mother worrying about what they should put in their suitcases to carry to the National Guard Armory in Lodi, where buses would take them to Stockton. “I tried to sneak some comic books in. My mother said ‘You should carry an extra pair of underwear,’ so I threw the comics away.” The 16 year old did pack some engineering boots that were popular at the time, and a pair of Levi’s pants.

The removal of Lodi’s Japanese community to newly constructed tar paper barracks on the San Joaquin County Fairgrounds came on a school day. Gary Shioto didn’t get to say good-bye to his classmates. Most of them he never saw again.

Those held at the fairgrounds were primarily from San Joaquin County. The fairgrounds were a couple miles southeast of downtown, and about half of the population stayed in barracks built inside the fair’s racetrack, and the rest adjacent to it. The assembly center wasn’t finished, as rain and logistical problems had held up construction. Crews were still on the site when the first to be incarcerated arrived on May 10, 1942.

Some lessons may have been learned from other assembly sites. No one was housed in horse stalls, although that was planned. An urgent notice had come from the War Relocation headquarters to nix it. Latrines were ventilated and had screens, unlike some other centers. The bathrooms had flush toilets, and late plumbing work had increased the number of shower heads. However, slightly better facilities did not negate towers with armed guards, nor barbered wire on fences surrounding the enclosure.

Once the rains stopped towards the end of May, the Valley summer heat soon set in. It would be 110 degrees on some days. Refuge was sought under the racetrack grandstands or in the barracks. Although the barracks windows didn’t have screens so if you left them open mosquitoes could create misery. There was no formal school, which let teenagers like Shioto hang out with friends, unimpeded by adults.

In an interview in 1944, Tsugio Kubota said that at the holding facility the rural kids from around Lodi had been influenced from hanging out with the city youth from Stockton. As an example, he referenced dances that the young people put on during the summer of 1942 while in custody. He said they would never have been allowed to go dancing back home.

When the entire population of the Stockton Relocation Center was transferred to Rohwer, Arkansas in the fall, the San Joaquin County teens apparently upped their hipness by mixing with the urbanites from Los Angeles, who had “pachuca” style haircuts and wore zoot suits.

Rohwer Concentration Camp

The assembly center had at least been in Stockton, a city most of the Lodi area Japanese and Japanese Americans had visited. Their next destination must have seemed like the end of the earth. The Mikami family arrived on October 7th at the Rohwer War Relocation Center. It was situated on abandoned land and in the middle of nowhere in southeastern Arkansas. Unlike Colorado’s governor, Arkansas’ Homer Adkins didn’t want a camp in his state. Yet Governor Adkins ended up with two, the other being in Jerome.

Moreover, the Rohwer property had been taken over from the Farm Security Administration after the former owners failed to pay back taxes. It had not been kept up for years. The land was flooded in places and tree stumps stuck up where fields might have been plowed.

It was all very depressing. Actor George Takei later described his boyhood memory among the prisoners from California arriving in Rohwer by train. “It rolled slowly alongside the barbed wire fence,” he recalled. “Beyond the fence, a distance away, we could see internees who had arrived earlier lined up and waving forlornly. Mama recognized a friend among the people out to greet us, and she managed a wan smile and a wave. Daddy just stared out the window in intense silence. With a final lurch, the train came to a stop. Our grueling three days and four night were over.”

Constructing the concentration camp was done in a rush. It took a long time to clear the land, some of which had to be drained, so the facility wasn’t ready when the group from San Joaquin County arrived in the fall of 1942. It took until November to get classroom instruction underway, which was impactful because about a quarter of those held at Rohwer were school age.

Jim Crow laws were still in effect in Arkansas and the local population didn’t, for the most part, seek laborers from a release program as was the case at most of the other sites. There was plenty of acreage to farm within the camp boundaries, once it was ready in the spring of 1943, and crops grown included about a hundred different fruits and vegetables, which greatly improved their meals. That was important because the amount spent by the government to buy food for prisoners at Rohwer was just 37 cents a day.

Daily Life Inside

Besides the improved diet, those incarcerated at Rohwer had a couple of friendly faces in Joseph Boone Hunter and his spouse Mary. The Hunters had met while missionaries in Japan and spoke fluent Japanese. Joseph was previously a pastor in Arkansas and returned to be one of the assistant camp directors at Rohwer. He was responsible for community relations, which meant oversight of religious observance, education, sports, and social events.

Sports were a part of life for the boys and men held in Arkansas. Ball fields were prepared and uniforms made. One man commented that playing ball reminded him of the good times back home and lifted his spirits. Basketball was popular, too, along with football, and judo. There were outdoor activities for scout troops, with youngsters earning merit badges and reciting the Boy Scout Oath and Law.

Popular culture existed at Rohwer in many forms. The teens had their dances. Adults formed musical groups, some of whom played for social events. And a true treasure was Fujima Kansuma, an expert in traditional Japanese performance and culture. She had performed when Angelenos had been held at Santa Anita Racetrack, and did so again at Rohwer. Kansuma was so popular that word got to Jerome and she was invited to the neighboring facility 30 miles distant. By then, Rohwer and Jerome had become the fifth and sixth largest towns in the state.

Despite the lack of offsite employment on farms and other release work those who were college age, and some adults, were granted leaves from Rohwer starting in late 1942. Matsuto Mikami, now going by “Jim,” was one of those who sought vocational training in the Midwest, going to Toledo, Ohio and Detroit, Michigan. At one point he took a course to become a butcher. His parents and siblings remained imprisoned.

In February, 1943, the government presented a questionnaire at all ten concentration camps. It asked a number of items but focus on two questions was paramount. One asked if those kept behind barb wire would renounce loyalty to the emperor. The other asked men if they would volunteer for the military, or if female, for non-combat government service.

The whole polling process was poorly conceived and caused confusion and resentment. Understanding what was being asked of them especially confounded elders who could not read or write English fluently. The survey was not well received at Rohwer, but those held at the other prison camp in Arkansas had a virulent response. Almost none of the eligible men at Jerome said they’d go in the military—and the number of no-no respondents was very high. The Jerome camp was deemed to be problematic.

By summer of 1944, federal authorities had reacted by transferring thousands of Jerome resistors to Tule Lake, which was already a hot bed of dissent and violence. Jerome was then closed, and the remaining 2,500 men, women and children of Japanese ancestry were transferred to Rohwer. That brought the population to almost what it had been right after it opened. Rohwer was the last incarceration center to close, in November of 1946, the same date as Tule Lake was shut down for good.

Return To Lodi

Teruichi Mikami had already returned to Lodi by then. He was released on April 18, 1945, apparently to find work and a safe place for his family to live. Jimmy would follow, with Mitsuyo and the rest of her children departing Arkansas on August 17th. They initially stayed in the barn of a family of that had stored some of their household goods.

The displacement of the Japanese community in California, Washington and Oregon had begun after Pearl Harbor. It continued as incarcerated Issei and Nisei men and women were released from camps to attend school, vocational training or work in the interior of the country. Additionally, thousands of Japanese Americans had joined the Army to fight in Europe or serve in military intelligence in the Pacific.

The families that came home intact, as the Mikami’s did, were in the minority. Forcing them out introduced new choices for how they wanted to live their lives and make their livings. A number chose to stay in Denver, Chicago, Salt Lake City, or New Jersey, where a frozen food company had recruited many second-generation Nisei who were themselves starting families. Of the 33,000 Japanese Americans who served in the U.S. military in World War II, 800 were killed. Many Nisei veterans stayed when the U.S. occupied Japan after the peace treaty and later went on to work for the government in other jobs away from where they grew up.

John Wilson’s research on property sales involving Japanese and Japanese American owners in San Joaquin County and Sacramento County showed the enduring impact of Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066. “Internment proved to have a significant and deleterious effect on Japanese American land ownership,” Wilson concluded, adding most of Japanese American land sales after the war happened because of the permanent out migration that followed removal and internment.

But the Mikami family didn’t leave, they invested in Lodi’s grapes. Jim Mikami continued to live with his parents and some of his siblings on rented farmland. His father Teruichi finally was able to own property after becoming a citizen, buying 40 acres of grape vines in the mid-50’s.

Jim sought a life’s partner, and a marriage was arranged to Aiko Ninomiya in 1958. She had grown up in Hiroshima Prefecture, and was 15 when the U.S. dropped an atomic bomb on Hiroshima. Aiko was injured and her brother was killed. Despite the scars, both physical and emotional, she began a new life with Jim in Lodi.

They started a family with the birth of a daughter, Ellen, and in 1963 Jim and Aiko bought their own place, a 15 acre farm on West Sargent Road planted in Tokay and Zinfandel grapes. It was not far from the first settlement a century before in the Turner Road area whose pioneer families attracted the railroad line. Their son Jason was born in 1970.

Grapes had been grown on the property since 1902. Zinfandel had been planted to complement the Tokay vines 20 years later. The farm was a one man operation, except at harvest time. Jim had a small tractor, the rest was mostly done by hand, the kind of precise husbandry that his father had passed along over several decades.

The grape industry had been evolving in Lodi, however, particularly in what was popular with consumers. Tokay grapes for eating had fallen off in favor of seedless varieties, but even though a seedless Tokay hybrid had been developed, the trend couldn’t be reversed. The sweeter wines made from Tokays before the war also lost appeal, and growers in the region were turning to grapes like Zinfandel and seeking to position wines from Lodi as worthy of awards and the higher prices that often go with acclaim.

Japantown’s Demise

By the time Jason Mikami was growing up, Lodi’s Japantown was fading away. “I never thought it was a thriving area,” he recalls. The Buddhist Church was still a hub, but more of its worshipers were seniors now. There were still Japanese American businesses downtown, and his favorite was Okazaki’s at 20 Main Street. Agnes and Tokuo “Ted” Okazaki had opened the store in 1948 to sell Japanese food and sundries. But the star of the place, especially in Lodi’s scorching summers, was their snow cone maker. Lines would form so children, and adults, could choose the flavor to be poured over their ice shavings held in a paper cone and cool off for at least a few minutes. Decades after Okazaki’s closed in 1983, its shaved ice offerings made a list of places Lodians, including Mikami, remember fondly from years gone by.

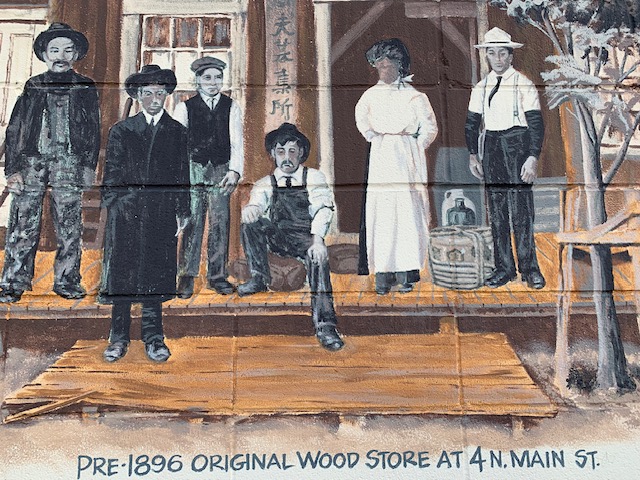

His mother, Aiko, had brought to Lodi a passion for Japanese culture, particularly the art of the tea ceremony. She was also accomplished musically, playing the koto and shamisen. Lodi’s Japanese community is memorialized with a set of murals by Tony Segale on the wall of a building on East Elm Street next to the Buddhist Church. It’s part of the city’s art in public places program. Aiko Mikami is portrayed in one, playing her shamisen, with a group women musicians.

Mikami says he did not consciously note the “brain drain” that had affected California’s Central Valley once veterans used the G.I. Bill for education, often at coastal colleges and universities, and didn’t return to Lodi and other Valley towns and cities. The larger shift preceded him in the Boomer generation, the Valley kids who went off to college in the 60’s and 70’s. He was part of an “echo” in the 80’s and 90’s that again saw the loss of Central Valley young people to the Bay Area and Los Angeles. “I didn’t really think about it,” says Mikami. “ I got decent grades and applied to colleges. We were poor, and that afforded me a chance to get a bunch of Pell and Cal grants to go to Berkeley.”

Mikami majored in East Asian languages at Cal, earning Phi Beta Kappa recognition, and later got a second undergraduate degree in electrical engineering and computer science. In between, he attained an MBA from UC Davis, where he was able to take some enology courses.

Jason Mikami combined skills in Japanese with interest in computing to launch a career in the semiconductor sector, moving from startups to over time becoming Director of Engineering for Uber, whose software enables ride sharing and delivery of ready to eat meals. His is a role at the forefront of the technology sector driving so much of California’s economy and enables split-second decisions to get people and things efficiently to destinations.

In contrast wine, part of California’s biggest industry, takes time. Yes, increasingly agriculture is run by computers, everything from milking cows to deciding when water should be delivered to an individual plant. But it is being present in the vineyards that means so much to the man who grew up with grape vines surrounding him every day, vines his father tended with such care and patience.

Timing Is Everything For A Wine Grower

The year Jason was born happens to signal a turning point for wine grapes in the Lodi region. In 1970, 90% of the grapes grown in northern San Joaquin Valley were crushed for wine, with the remainder going to consumers as table grapes. Tokay grapes made up less than a third of the acreage. The wines produced were largely for mass consumption.

By the time Jason went off to college, an increasing number of Lodi area growers were starting to think about varietals that could produce premium wines. They organized around that idea, fueled in part by a new generation that had studied enology at UC Davis and other universities in California. They had returned home to accelerate the new direction.

Jim Mikami was committed to the Tokays in his fields. Besides sentiment, it would be expensive to pull them out, plant new root stock and wait for mature fruit. Taking care of his vineyards was becoming more difficult as he approached his 80’s, and then he fell off a ladder and was partially paralyzed. Jason had been helping his father, but soon had to start making decisions about managing the property.

He decided to point in the direction of premium wines and the Tokays came out and were replaced by new Zinfandel plantings. When his father passed in 2005, Jason mapped a path forward for Mikami Vineyards, one that finds him and his spouse Mitzi Onizuka as partners seeking exceptional wines from a portion of their 15 acres.

They do it with a team that includes Kian Tavakoli, a winemaker who shares the UC Davis link, and Mike Manna, who manages the vineyard and brings his own multi-generational legacy in grape growing. The results have been rewarding, with award winning Zinfandel, and now meritorious Petite Sirah. But prizes are not the most important part.

“This was just my way of still being connected to the land, my family, and our Japanese American history,” says the juggler with two professions. “It sort of encapsulates all of that for me. For me to give up the vineyard, that would be a loss of the connection.”

Mikami Vineyards only makes about 600 cases a year. It’s 15% or less of the vineyard’s product each year. The rest is sold to other winemakers.

To make this duality of living possible, Mikami estimates he works 60 hours a week. He lives in the Uber world Monday through Friday, with winery business primarily on the weekends. It’s clear the work ethic of his grandfather and father transcends.

In the background hums the question about the century and a quarter through line that the Mikami’s draw from the late 1800’s to today on northern San Joaquin County farmlands. For there’s the next Mikami generation represented by Jason and Mitzi’s teenaged daughter, who has already helped with harvests and berry sampling to assess the development of maturing grapes.

“I tell my daughter when we’re together in the vineyards that I feel fortunate to have grown up in Lodi, and the conditions I grew up in. And to now live in the Bay Area and a very urban environment, and be in tech.”

Something seems to already have passed, once again, from one Mikami generation to the next. “There is an interest,” Jason Mikami tells AsAmNews. “She says she’ll never sell the land.”

AsAmNews is published by the non-profit, Asian American Media Inc. Follow us on Facebook, X, Instagram, TikTok and YouTube. Please consider making a tax-deductible donation to support our efforts to produce diverse content about the AAPI communities. We are supported in part by funding provided by the State of California, administered by the California State Library in partnership with the California Department of Social Services and the California Commission on Asian and Pacific Islander American Affairs as part of the Stop the Hate program. To report a hate incident or hate crime and get support, go to CA vs Hate.