By Jia H. Jung, California Local News Fellow

It’s Marathon Monday – the 128th Boston Marathon is hosting some 30,0000 runners from 100 different countries who have met the stringent time qualifications for the premier event. The entrants pushed off from the Hopkinton, Mass. starting point in four massive waves launching from 10 a.m. through 11:15 a.m. Eastern Time.

These days an increasing number of people around the world are participating in marathons and ultra marathons for the athletic challenge and international exchange. But it wasn’t always this way.

Boston’s race is the oldest consecutively held marathon in the world, continuously administered by the Boston Athletic Association (BAA) since 1897. The marathon’s 50th anniversary on Saturday, April 19, 1947 had 184 mostly participants.

The winner that day was 5-foot-1-inch, 24-year-old Suh Yun-bok of Korea, with a world record marathon time of 2:25:39. He was the first to set a record in a breakaway while on the three-mile homestretch to the finish in Boston’s Back Bay after the grueling “Heartbreak Hill” in Newton Center.

LATEST STORIES

Reporter Jerry Nason wrote in The Sunday Boston Globe: “It was here, at the most critical stage of this savage international struggle, that a fox terrier came rushing out of the crowd and plunged directly between the chunky little legs of Yun Bok Suh.”

Suh, who had been running for the past several miles with the laces of his right shoe undone, fell down onto the concrete of Commonwealth Avenue. Somehow, he recovered, took back his spot from the Finnish contender who had passed him, and continued negative splitting his way up the infamous hill. Finally, according to the Globe, he “stormed, imperturbable as a clam in a chowder, to the Exeter Street finish line.”

Nam Sung-yong, 34, bronze medal winner from the marathon of the 1936 Berlin Olympics came in twelfth.

The newspaper, which had described Suh as a wee, little, brown, toothy, Oriental mountain man who was “pert as a robin” with “gleaming black hair,” concluded: “The sun, at long last, had really risen for the land which had been under the heel of the Rising Sun for generations!”

This referenced how Korea had just been liberated from 35 years of colonization by the Japanese empire with the end of World War II. By 1947, much of Korea remained impoverished and in a state of political turmoil.

A South Korean film called Road to Boston (2023) dramatized what it took for Koreans to scrap together a marathon team, raise the money and connections to travel to and stay in Boston, and appeal to the BAA to be able run with Korean flags printed on their shirts even if sovereignty had not yet been fully restored to the nation after the removal of Japanese colonizers.

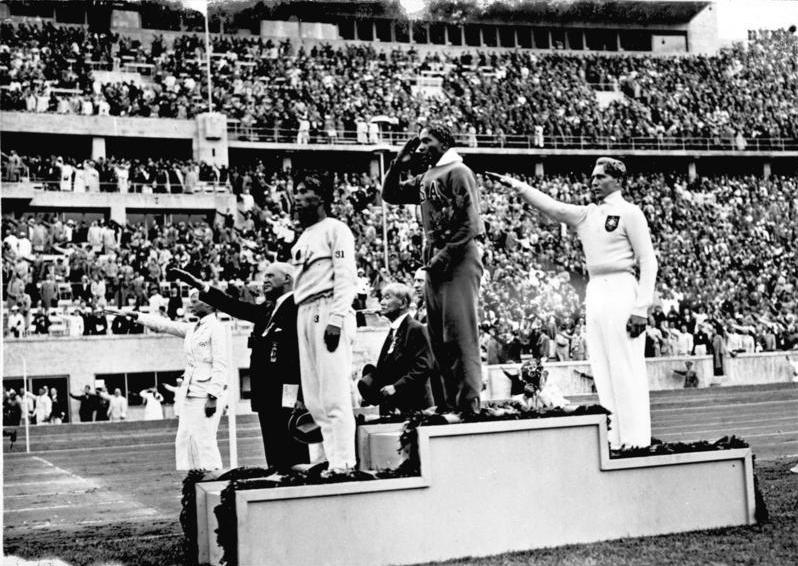

Suh’s coach for the momentous run was Korean gold medalist Sohn Kee-chung, the first non-Western winner of the Olympics marathon event at the 1936 games in Berlin, where Adolf Hitler gave the opening speech and led thousands in the Aryan nation salute. Sohn stood on the podium in first place under the assigned Japanese name Kitei Son. His Korean teammate, Olympic bronze medalist Nam Sung-yong (“Nan Shoryu” in Japanese) was in third place, with Englishman Ernest Harper in middle in second.

In Berlin, Sohn had signed his name in Korean and drawn maps of the Korean peninsula beside it at every opportunity to show where he was from. Transcending language barriers, Sohn and American sprinter Jesse Owens befriended one another, training alongside one another for their separate events.

Owens, a Black man living in the Jim Crow era in the U.S., outshone the brewing storm of Nazi Germany by becoming the first American athlete ever to win four gold medals in track and field events in a single Olympics. After becoming the first Asian athlete to win an Olympics marathon since the event began in 1896, Sohn used his moment to tell the international press over and over that he was Korean.

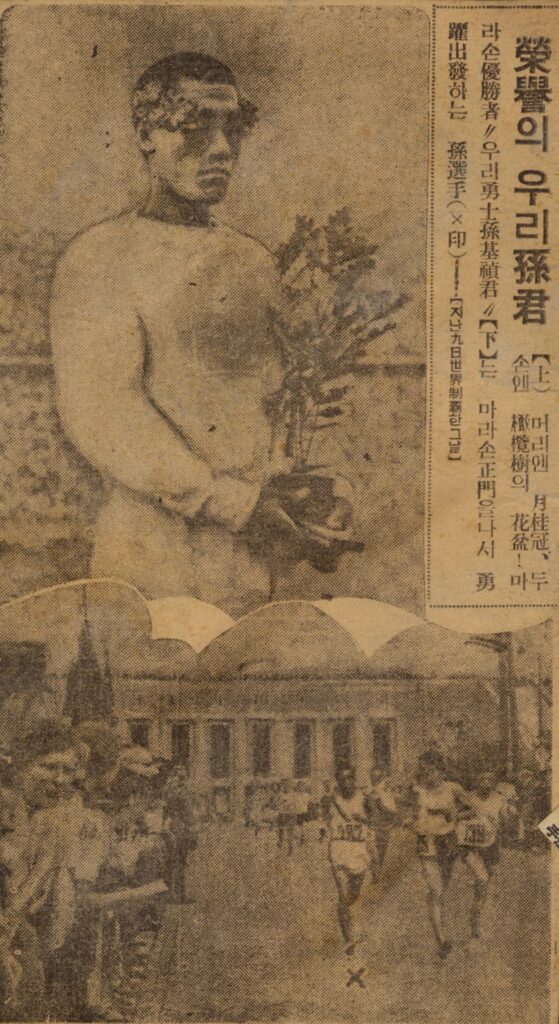

As two rising sun flags rose and the Japanese anthem played overhead, Sohn kept his laureled head down and held close an oak sapling in a pot that had been presented to him so that the baby tree’s leaves obscured the red dot on his chest.

When the Dong-a Ilbo newspaper printed an image of Sohn with the Japanese flag edited out of his chest, imperial Japanese police imprisoned eight journalists and shut down the newspaper for nearly a year.

Sohn receiving his gold medal in Berlin on Aug. 9, 1936, and the Dong-a Ilbo image edit on Aug. 25. Der Spiegel

A Sports Illustrated retrospective in 1968 clarified Sohn’s Korean ethnicity after records kept claiming his victory as Japanese. In 1988, Sohn lit the torch to open the Seoul Olympics. But Olympic records still list Sohn’s achievement under Japan. Every Olympics, the sore point comes up again, decades after Sohn passed of pneumonia in 2002 at age 90.

In 1992, Korean marathoner Hwang Young-cho became the second of only two Asians, both ethnically Korean, who have ever won gold in the men’s Olympic marathon thus far. Significantly, Hwang received his medal under the flag that properly reflects his nationhood.

Japanese women – Naoko Takahashi, with a time of 2:23:14 at the 2000 Sydney games, and Mizuki Noguchi, with a time of 2:26:20 in Athens in 2004 – are the only women of Asian descent to have won the Olympic marathon after the female competition category opened in 1984.

After Korea’s 1947 debut in Boston, coach and Olympic gold medalist Sohn told The Boston Globe: “We have six or seven men just as good as these three in Korea… it would have been nice to bring them all, but our country is poor.” His translator was Homer Kim, a Boston merchant, one of the early Korean immigrants in Boston, who along with the family of Norman Paik in the town of Dedham, Mass. helped make the Korean athletes at home.

On April 19, 1950, months before the outbreak of the Korean War on June 25, three Korean runners – Ham Kee-yong, 19, Song Gil-yun, 19, and Choe Yun-chil, 20, swept first, second, and third place in a “Korean Grand Slam” of the Boston Marathon.

The Globe went wild, praising Koreans as “the Irish of the East” for their “gayety and quick intelligence,” and attributing their victories to their physiques generalized as natural to all Koreans and advantageous in running. Another Globe story marveled at how the young Korean men were more eager to secure higher education than go to party with the gals of Boston after their victories.

The irony of this unbridled complimentary stereotyping is that people on both reputable and unverified online forums to this day muse over whether some broad genetic limitation, politics, or cultural emphasis on studies over athletics is why Asian people worldwide are participating more in track and field and long distance running events than ever before but so rarely win.

Opportunity at the elite, international levels has historically been determined by diplomacy between countries, the decisions of entities organizing the competitions, and financial support for a country’s athletic program and its athletes. Most of this power, authority, and money originated in the West, where events such as the Olympics and the Boston Marathon were conceived.

When the Korean peninsula became embroiled in warfare in 1950, the BAA shut the door on Korean athletes participating in the Boston Marathon until further notice.

Then came a steady stream of Japanese marathoners starting right in 1951. This continued once Tokyo hosted the Olympics in 1964 and the U.S. eagerly normalized relations with Japan in hopes of maintaining a presence against Communism in the Asia-Pacific.

Most recently, Japanese Yuki Kawauchi, beloved for being a self-supported athlete and full-time office worker, won the men’s category in Boston in 2018 in terrible wind and rain in 2:15:58.

Kawauchi was the first Asian champ since Lee Bong-ju of Korea in 2001. Lee, who had won a silver medal for South Korea at the marathon of the Atlanta games in 1996, broke a 10-year streak of Kenyan champions of the Boston Marathon in 2001 with a time of 02:09:43 – sub five-minute miles all the way.

In 2021, Lee revealed to the press that he had been debilitated by the progression of Dystonia Musculorum Deformans, a disease that causes involuntary muscle distortion. A March article from Maeil Business News Korea announced that Lee, now 54, has since miraculously recovered his health, discarding the wheelchair and cane he was using before.

Throughout the mid-1970s, after the Boston Marathon opened the race to women in 1972, Michiko “Miki” Gorman won in 1974 and 1977 and also won the New York City marathon in 1976 (at age 41, after giving birth to a baby) and 1977 (becoming the first of only two women who has ever won Boston and NYC in the same year).

Gorman, an ethnically Japanese American born in 1935 in a Japanese-occupied part of China while her father served in the Japanese imperial army, remains the only woman of any background to have ever won both the Boston and New York City marathons twice.

For the wheelchair category of the Boston Marathon that began in 1975, the only Asian winners have been Japanese as well. Masazumi Soejima won in 2007 and 2011. Hiroyuki Yamamoto followed suit in 2013. For the women’s wheelchair category that began in 1977, the only Asian winner has been Wakako Tsuchida from Japan, victorious for five years in a row from 2007 through 2011.

The Koreatown Run Club: You don’t have to be Korean and you don’t have to be elite

Runners of Korean and Japanese descent have been the only Asians to win the Olympic and Boston marathons. Why? Or, why not anyone else?

“It’s embedded in the culture – we enjoy the suffering,” said Simon Joo, 38, one of the captains of the Koreatown Run Club (KRC) in Los Angeles. He was scarcely joking, having just completed his first world major marathon in Tokyo on March 2 and the Seoul marathon on March 17, alongside dozens of KRC friends.

According to Joo and his teammates, the fervor for running was palpable in South Korea and Japan, maybe a bit more so in Japan.

On a regular Wednesday night in Los Angeles the week before the big race in Boston, hundreds of KRC runners milled about at the bottom of the steps to the Los Angeles Community College (LACC) Rainbow Track, thus named for its six Lucky Charms-colored lanes.

Some stood, swayed, and stretched in fleets of lean, mean bodies, with shiny legs and feather-light running shoes on full display. Others arrived alone or in variegated mini clusters, wearing oversized eyeglasses, art tees, and loose shorts or sweatpants, eyes darting around to get the lay of the land. Another guy showed up with crutches tucked under his armpits.

The tall gates, initially locked after usual business hours, opened, and the hordes ascended the stairs at an eager but uncompetitive pace. Feeling safe, they left their little bags of belongings in the ample space above and filled the field at the center of the track for exercises.

Afterward, the masses separated into groups by projected marathon paces. The distribution of the paces was surprisingly even, with a sizeable number of people joining the 6-hour-plus category, calculating to approximately 13-minute miles.

The groups ran for five minutes at their respective paces, cooled down for a minute and a half, and resumed, continued this pattern until a longer break during which everyone sang happy birthday to a member of the club. Some of the runners hit the track again for an optional sprinting set while others stretched, hydrated, and chatted with one another.

This was one of four consistent events on KRC’s schedule, which include Saturday long runs, and three to five-mile Monday “block runs” embarking at Wilshire Boulevard and Oxford Avenue. Block runs originated during the pandemic when different subgroups met on separate blocks to minimize crowding while still being in it together.

Thursdays, after track Wednesdays are wind-down socials at Love Hour, a Smashburger joint co-owned by KRC’s co-founders Duy Nguyen and Michael Pak. Here, people have the choice of running up to five miles if they feel like it before eating, or, go straight to the food. A single cheeseburger with a side of chili cheese, perhaps, or a juicy double, plus fries sprinkled with sour cream and onion flavoring, all washed down with a mini-Coca-Cola, a refreshing diet soda, a cocktail, or a pint of jasmine rice lager on draft at the bar.

On the side of Love Hour, Pak also organizes Bicycle Meals, a local-impact operation of volunteers delivering nutritious brown bag lunches to unhoused people in Koreatown on Sundays. As with KRC, all someone has to do to partake is show up.

The KRC has amassed plenty of buzz by now, especially locally and in the running community. The group also has a partnership with Nike, invests in and holds market research meetings with KRC’s community as part of the company’s current strategy of returning to its roots as a running shoe while promoting diversity in athletics overall.

People in the city who have never gone out with the run club but have heard about it talk a certain degree of crap. They might point out that Nguyen and Pak aren’t even from Koreatown, or L.A., or even from California, for that matter – they’re from Virginia.

They say that the real person who’s behind the Love Hour is Jimmy Han, owner of Beer Belly and Frank ’N Hank in K-town. They question why Pak, who’s had the Instagram handle @koreatown since his high school days, gets to be the “unofficial mayor of Koreatown” as a 2020 GQ profile declared him.

Nguyen and Pak have always been open about being transplants to their neighborhood. And they never postured as brand leaders of a growing social scene, saints in a worldwide struggle for diversity and inclusion in running, or spokespeople for the diverse, complex, and fluid communities that converge around the common denominator of finding joy in running and health.

KRC is just the story of a group that organically reflects the diversity of its location. For this reason, people have been known to travel in from more homogeneous parts of SoCal and beyond to run with a community where they feel belonging and inspiration.

Nguyen first brought up the idea of a running group to his friend Pak upon returning from a filming assignment at the 200-mile Run Across Haiti. He had witnessed the way that running could bring people together and wanted to create the same effect even though he had never formally run in his life.

Born in Vietnam and raised in Virginia from infancy, he had missed out as a kid on the concept of signing up for sports teams but enjoyed the activities he did access through physical education at school and taekwondo class. KRC rapidly turned him into someone who still swears he has trouble getting started on his runs but has completed over 20 marathons over the past several years.

The frequently asked questions section of KRC”s website makes clear that one does not have to be Korean to roll with KRC – the name of the club is based sheerly on its location. And that doesn’t mean you have to be a born resident of K-town to run with KRC, either. You can be anyone from anywhere.

Even as the KRC grows by leagues on almost a daily basis, its programs remain free and open to all, and membership continue to be devoid of applications, registrations, or dues.

No matter how big the gatherings get, people know each other by name. If they don’t, they learn quickly and bring newbies into the fold.

Curious visitors to the club, however they find their way to it, become seduced by the welcoming energy, safety in numbers when running while Asian in the era of anti-Asian hate crimes, and group accountability.

There is no fine print stating that the ultimate goal of running with KRC is to enter and complete a marathon, yet lots of joiners freefall into a vortex of marathons, trail runs, and ultra marathons after passing through the yawning gateway to the intoxicating subcultures and international networks that surround endurance and extreme sports.

At the same time, Nguyen confirmed, “Definitely, at the top, long distance running, in America at least, is very White or whatever. But if you look at runners, it’s a very diverse group and there’s a mix of everyone. So it’s different for me, because I see everybody, any color, body shape, running.”

When asked out on the rainbow track why he thinks running still isn’t more diverse at the higher levels, Nguyen said that he honestly doesn’t know – maybe socioeconomic factors, or other stuff he doesn’t know about.

He humbly downplayed the mass of people who went all the way to Korea and Japan last month, repping KRC with black tees shouting BRIDGE THE GAP in bold text.

“There’s clubs all over the world. And yeah, we have matching shirts,” he shrugged. He also emphasized that teams from KRC have gone to events all over the world, not just Asia, bonding with teams from the world over who have also been going the distance to run long distance.

KRC is truly one-of-a-kind but not the only thing out there. Among many other groups, Nguyen has cited admiration for NYC Bridgerunners, captained by Mike Saes and Cedric Hernandez in the big apple with the hashtag #BridgeTheGap, and the mission of building multicultural solidarity, accessibility, and equity through running.

KRC’s presence at the Seoul marathon was not organized by Saes or Hernandez but the tee shirts the KRC runners wore were a nod to the philosophy of the NYC Bridge Runners. The group responded by posting the event on its social media accounts.

When asked if enthusiastic runners from Korea ever visited KRC anyway because of the club’s name, Nguyen said, sure, but people came from all over the country and the world to run in L.A. because of the city’s renown.

“If we had a show of hands, I’m sure somebody here is visiting from somewhere,” he said.

As track night came to a close, a young man placed his neon orange shoes onto a blue running tank on the lawn and carefully photographed the set. Another young man soon joined him and the two sat cross-legged, speaking in Korean.

They were South Korean runner Won Hyeong-seok, 30, from Seoul and his friend Kim Min-seok, 24, from Busan, studying as an exchange student at the USC Marshall School of Business. The two met years ago while living and working in Seoul and deepened their friendship over a shared obsession with running.

Won and Kim recently completed The Speed Project, a 340-mile relay race with the tagline “It was better next year” from Santa Monica, Calif. to Las Vegas, Nevada through Death Valley. They ran the rule-less, spectator-less ultra event with the run club Eighty Eight Seoul.

Won is running the Boston Marathon under bib #719 while Kim cheers him on. The two will proceed to New York City just for fun before Kim returns to L.A. and Won goes back to Seoul.

Won, who also goes by “Stone,” picked up running in college and kept intensifying his involvement in the sport while also transforming from an emergency room nurse into a commercial filmmaker and YouTuber. He said that he had neither been to Boston nor New York City, though he had connections there, mostly through running.

He developed the desire to run Boston on his own; he only become aware of the legacy of Korean runners in the city thanks to the 2023 Korean movie.

His first time in the U.S. was to run the Chicago Marathon last year, where he met KRC captain Joo.

“I loved the sense of freedom but everything was so expensive!,” Won lamented, of his first impression of America in the windy city. He chuckled that pizzas and burgers had suited his taste better than he thought they would, but emptied him out financially.

He qualified for the Boston Marathon through his Chicago performance. Kim piped in that Won was one of the fastest amateur competitors in all of Korea.

Nguyen, 34, said that qualifying for the Boston Marathon this year was particularly tough because the cutoff times were shaved down even further by “buffers” – deductions in qualifying times curved to how competitive the applicants are for the race any given year. This means more competitive the applicant pool is, the more selective the qualification times get so that the organizers can eliminate the excess applicants.

This year’s buffers prevented lots of people from being able to participate. Only five were representing the KRC, and Nguyen is one of the five, running under bib #29889.

If what he fears is plantar fasciitis stays at bay and doesn’t cause excruciating pains in his heels, this race could be the start of his third round of completing all the “majors” – the Boston, London, Berlin, Chicago, New York, and Tokyo marathons – if he can qualify for and/or get into all of their lottery systems.

Ryan Sung, 27, another KRC captain who happens to be Korean American, is also in the party of five heading running in Boston under bib #1811. Unusually, Boston is his first major international race before continuing onto his second in Chicago this October.

Sung grew up outside of Los Angeles as a “waterboy” in the swimming, water polo, and surfing junkets.

“Running was the devil” to him until he went to San Francisco for a job and lost the easy access to open water and outdoor pools that he’d enjoyed in Southern California. As a goal-oriented, competitive person, he decided to start running around the streets of San Francisco to stay fit. Within a week, the beautiful scenery had him signing up for the SF Marathon.

When his current job brought him back down to Southern California, he looked into joining KRC because he already had a “brand crush” on the group and a friend who was active in it.

After training with KRC, he knocked a whole hour off his first marathon time and completed the 2021 L.A. marathon in three hours and 22 minutes. After that, he worked with one of the KRC coaches who was also his friend, and with whom he had co-coached a team for The Speed Project.

He prepared for the California International Marathon (CIM) on Dec. 3, 2023 with a dream time of 2:45 in mind. He met that time with 15 seconds to spare and finished the run in 2:44:45.

“That was the race of my life,” Sung said, confiding that he had cried afterward from the catharsis of all his hard training, paired with the discovery that he was still capable of improving as a runner.

In February of this year, he completed his first 100K ultra marathon at the Sean O’Brien trail run in Malibu. His younger brother has taken to crewing all these races.

“He’s like my biggest supporter. He’s starting to get into running, because one of my toxic traits is getting the people I love into running,” Sung guffawed. “I actually I think my cousin is out here tonight because I pressured her to come out to run, too!”

Sung has a private goal for the upcoming Boston marathon but still considers it more of a victory lap after the CIM performance that qualified him for the race. He will use Chicago, his second major, to ramp back up again.

Sung said that running day to day in pursuit of seemingly extreme athletic achievements keeps him at equilibrium. He is open about his history of depression and other mental health challenges and how running helps him reach a meditative state he needs to survive.

“Running did literally save my life twice, and it means a lot to me,” Sung said. “And it’s given me community – I’ve met some of my closest friends and the people who mean the most to me through the run club.”

Andrew Park, 33, formed a deep friendship with Captain Sung over some of these same themes.

Park grew up in the suburbs West of Los Angeles in a predominantly White area but said he checked his American identity at the door before entering his bilingual Korean household. He mixed with diverse people mostly by playing various sports. These sports included golf, to please his father.

In 2019, Park was working toward a doctorate degree in physical therapy. As much as he wanted to be the son he believed his late father had wanted him to be, the path was not for him. The stress and unhappiness were taking a toll, and he was on the verge of having a mental breakdown.

Then, when the results of routine blood tests required by his educational institution came back late that year, doctors informed Park that he pre-diabetic and had high blood pressure, with a family history of both.

Park pondered thought of what steps toward healthy living had the lowest barrier to entry. He figured he had sneakers and clothes, and it didn’t cost anything to run outside.

He found his way to a KRC run and started in early 2020 by focusing on running a single block.

“I’m not gonna lie; I wasn’t hooked,” he said. But he stuck with it because the community kept him accountable for what he wanted to do for himself. He started to feel good and make friends. He began achieving, no, exceeding, his fitness goals, and started thinking out what he really wanted to do for his career.

New year’s eve, the last night of 2020, was a Thursday night block run for the KRC. The runners went around saying what they were thankful for mainly health. They were going to run for about four miles, when someone shouted, “Let’s do five!” Somebody else dared the group to crank out a full-on 10K – 6.2 miles.

“Let’s celebrate our health —let’s do it,” they decided. Going the distance with friends reeled Park headlong into marathons.

The Los Angeles Marathon was delayed because of the pandemic, so he ran it in November 2021. It took him forever but he finished, and followed up that race with the Honolulu marathon the next month. In 2022, he ran his first major in New York. Last summer, he his second in Chicago. This Sept. 28, he is destined for his third, in Berlin.

He is using the run to raise money for the V Foundation, an organization funding cancer research. On April 27, the eve of his personal new year, he is throwing a fundraising party in memory of his father, who passed away too soon after liver cancer metastasized into his bones.

Park’s answer for the persisting lack of diversity at the top levels of running was, simply, “artificial selection.” He said that Western Americans had hundreds of years of a head start on the idea of organized, competitive running. Everyone else was still catching up.

He admitted how sports can provoke feelings of nationality and tribalism. “A part of you jumps a little,” he said, in the rare moments of seeing elite, winning athletes who look like oneself.

But, he said, “Running is about celebrating athletes in their totality because it’s so individual. That’s why we welcome new runners and over explain everything.”

He said that he wears KRC on his chest in races but feels support from every other run club out there because only runners know the pain and glory that every single person goes through in the sport.

“What you’ll hear is a lot of different stories about why people got here,” Park said, in regard to KRC’s composition. “For some people, it’s a sense of identity within their own culture.”

Meanwhile, in Boston, PIONEERS Run Crew (PRC) formed just a year after KRC, purposefully organizing around the values of diversity, accessibility, and inclusion in race running as a direct counterpoint to what is still a very White scene.

On Saturday, PRC held its fourth 26.TRUE marathon – an untimed, unsanctioned, 26.2-mile race promoted with the slogans “our city, our way” and “run the culture.”

Approximately 200 people running the sold-out race embarked from Malcolm X Park in Roxbury at 8 a.m. and threaded through the most ethnically and socioeconomically diverse Boston neighborhoods of Jamaica Plain, Hyde Park, Mattapan, Dorchester, Southie, Downtown, South End, Allston, and Brookline, before ending back up in Roxbury.

Last year, WBUR radio of Boston reported disparities between some of these districts and the rest of the city. One stark difference was that the median household income in Roxbury is $42,211 a year, versus $141,250 in the Back Bay where the Boston Marathon ends. The life expectancy for someone living in Roxbury was also 23 years shorter than that of the average person in the rest of the city.

“You grow up in Boston, and you never have a chance to run the Boston Marathon, “ PRC member Jean Mike Remy said to WGBH News in a TV interview just a few days ago.

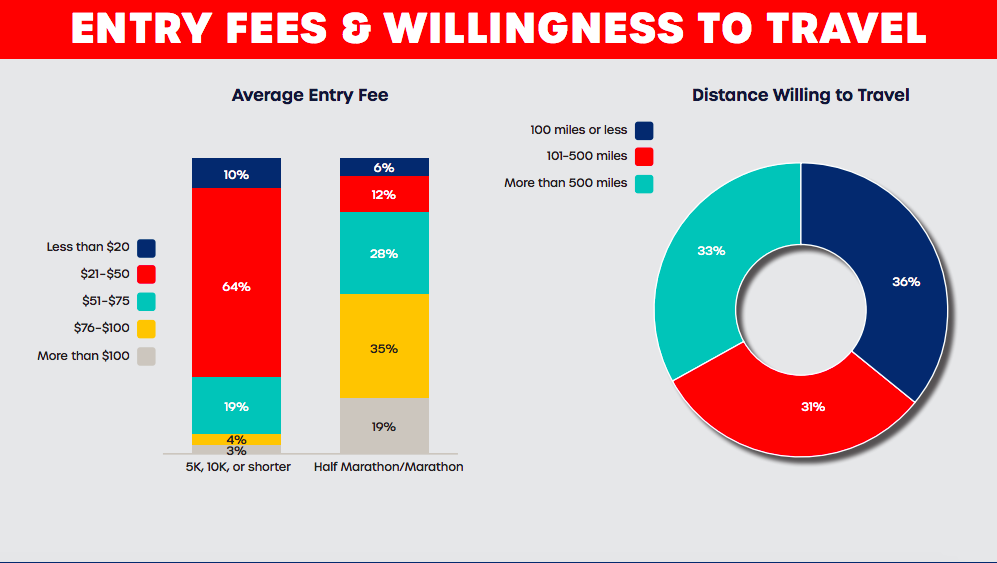

The Boston Marathon, for those who have the speed, conditioning, and training support to qualify, costs $230 for domestic entries and $235 plus untold travel costs for international registrants. 26.TRUE is $100, and fair game for all who register.

Footage from Saturday’s 26.TRUE race brightened the front page of Sunday edition of The Boston Globe, exulting that Boston mayor Michelle Wu had touted the race as the real Boston Marathon.

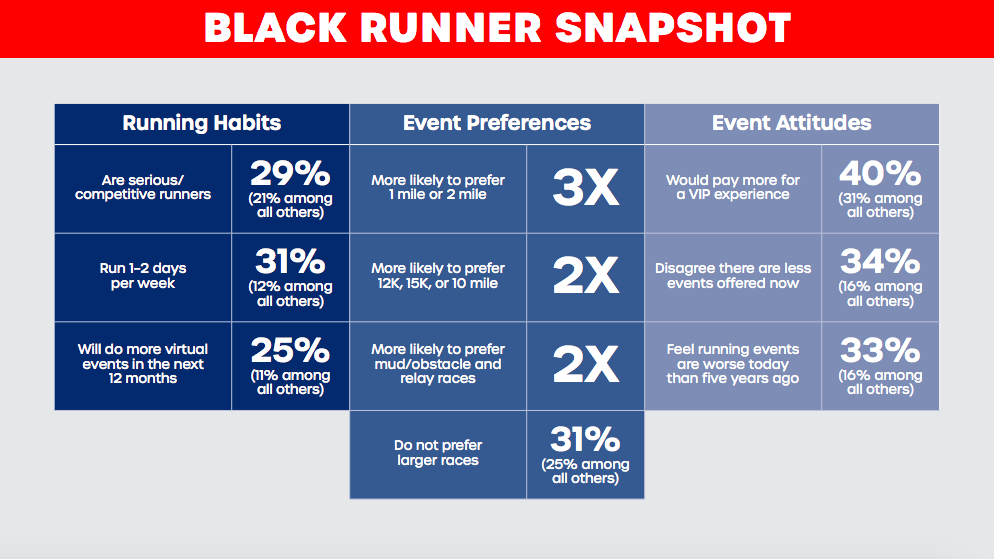

The article exposed the BAA’s latest demographic survey results for this year’s entrants: 1.5% of the respondents identified as Black or African American, 9% as Latino or Hispanic, and 10% as Asian or Pacific Islander.

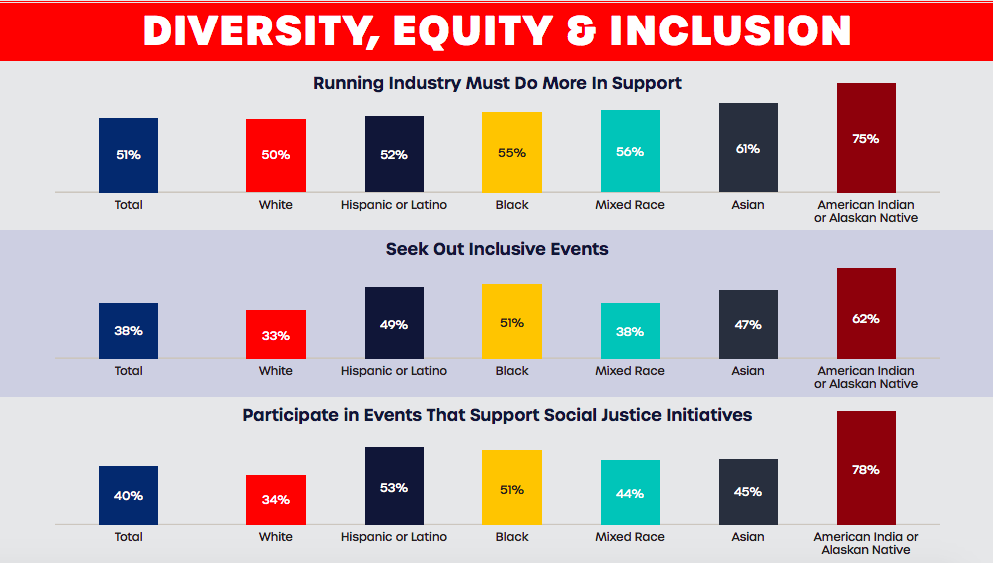

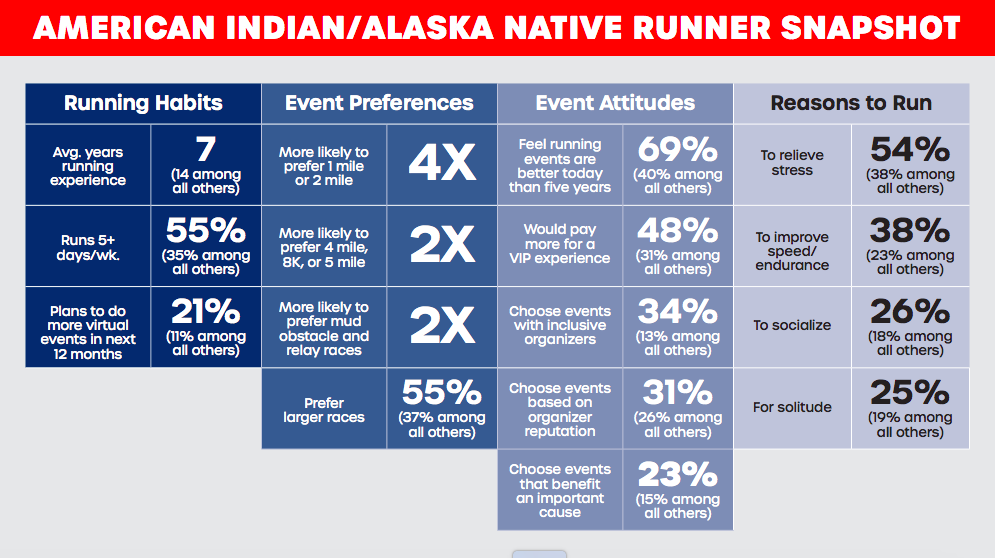

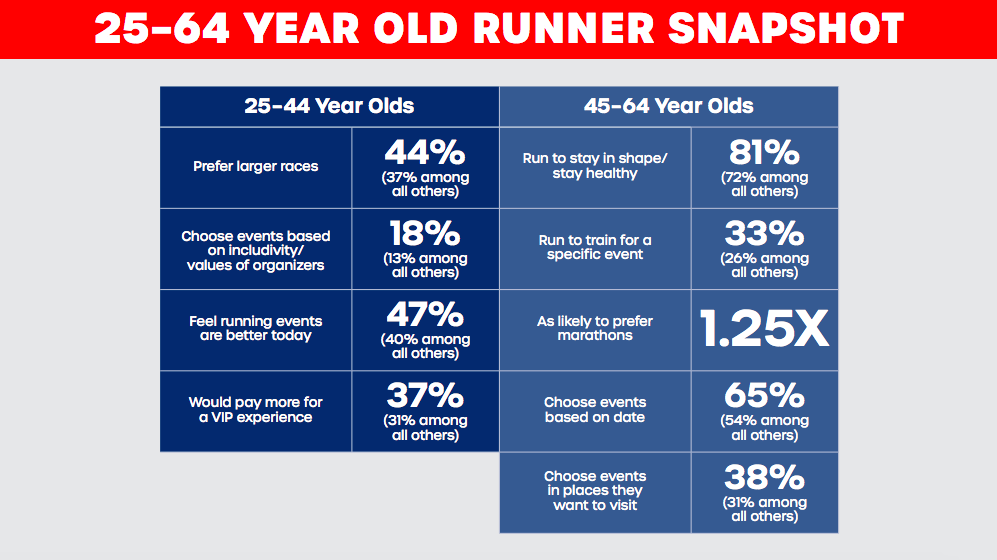

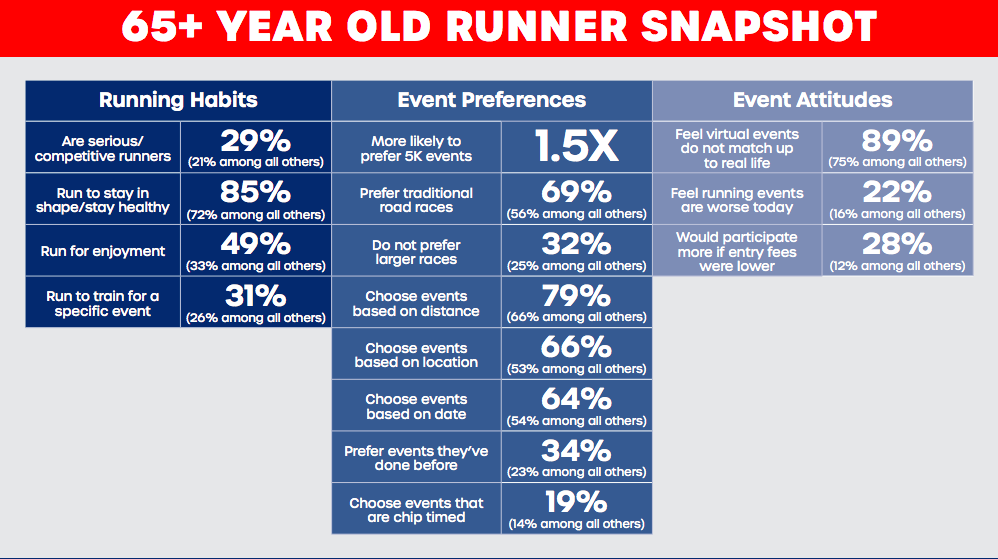

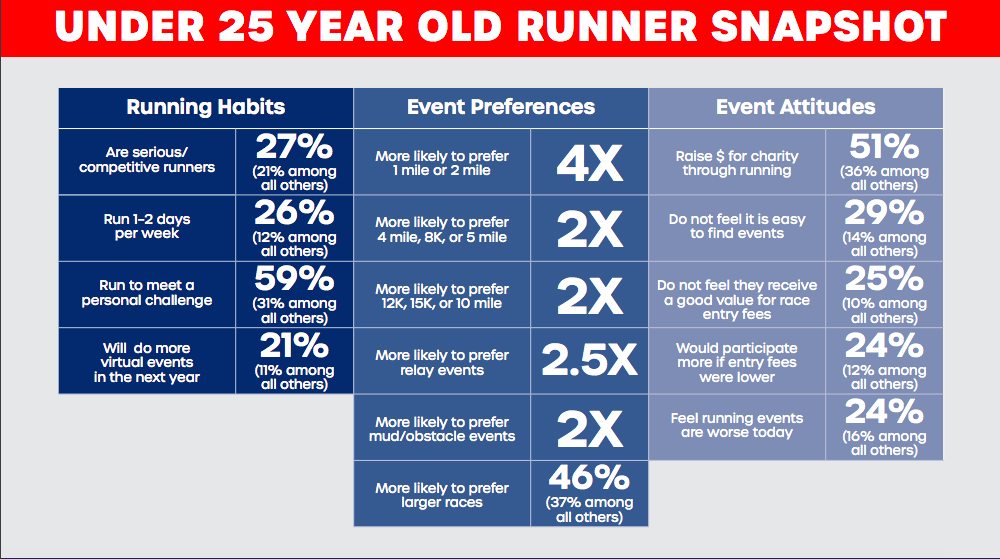

According to RunRepeat, 0.05% of the total U.S. population has ever completed a marathon. Running USA conducted a wider 2022 Global Runner Survey of over 5,500 people who identify as runners, defined by the organization as “a self-selected individual who participates in movement – running, jogging, or walking – at any point in time during the calendar year and may or may not participate in organized running events.”

Among the people self-identifying as runners, Running USA found that 2% identify as mixed race, 2% as American Indian or Alaskan Native, 5% as Asian, 7% percent as Black, and 20% as Hispanic or Latino. The remaining 64% identified as White.

An updated 2023 report, which surveyed 10,000 people, recently became available for purchase or download by members.

Today, tension may continue crackling between the people of Boston and one of the largest established authorities of marathon running. During last year’s Boston Marathon, Newton police blocked members of PRC and a partner club, the Black-led Trail BlazHers Run Co., from cheering zones by allegedly disrupting the official course by running along it while supporting their friends.

Many people felt mystified by the action and felt that it was selectively carried against diverse community members, further alienating Boston’s true population from the elite gatekeepers of the Boston Marathon. Trail BlazHers Run Co. is suing the BAA and the Newton Police Department for racial discriminataion.

“I have to ask that they cheer – everyone cheer – from the sidelines,” said BAA President and CEO Jack Fleming in a statement to WGBH News, after issuing apologies to both the running groups and the Newton police.

But whether buliding a crew that can find entry into events like the revered Boston Marathon or creating new spaces that anyone can join, the running communities of today and future will not likely be staying behind the sidelines any longer.

On this day, AsAmNews also wishes to remember Lingzi Liu, a 23-year-old graduate student of statistics from China who, along with 8-year-old Martin Richard and 29-year-old Krystie Campbell, was killed in the Boston Marathon bombing 11 years ago. In 2022, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the death sentence of Dzhokhar Anzorovich Tsarnaev, the surviving younger of the two bomber brothers. At the time of writing, Tsarnaev’s execution pends a review of federal guidelines for capital punishment, ordered by the Biden administration.

AsAmNews is published by the non-profit, Asian American Media Inc. Follow us on Facebook, X, Instagram, TikTok and YouTube. Please consider making a tax-deductible donation to support our efforts to produce diverse content about the AAPI communities. We are supported in part by funding provided by the State of California, administered by the California State Library in partnership with the California Department of Social Services and the California Commission on Asian and Pacific Islander American Affairs as part of the Stop the Hate program. To report a hate incident or hate crime and get support, go to CA vs Hate.